Russia: A Parallel Universe

by Karl Richter

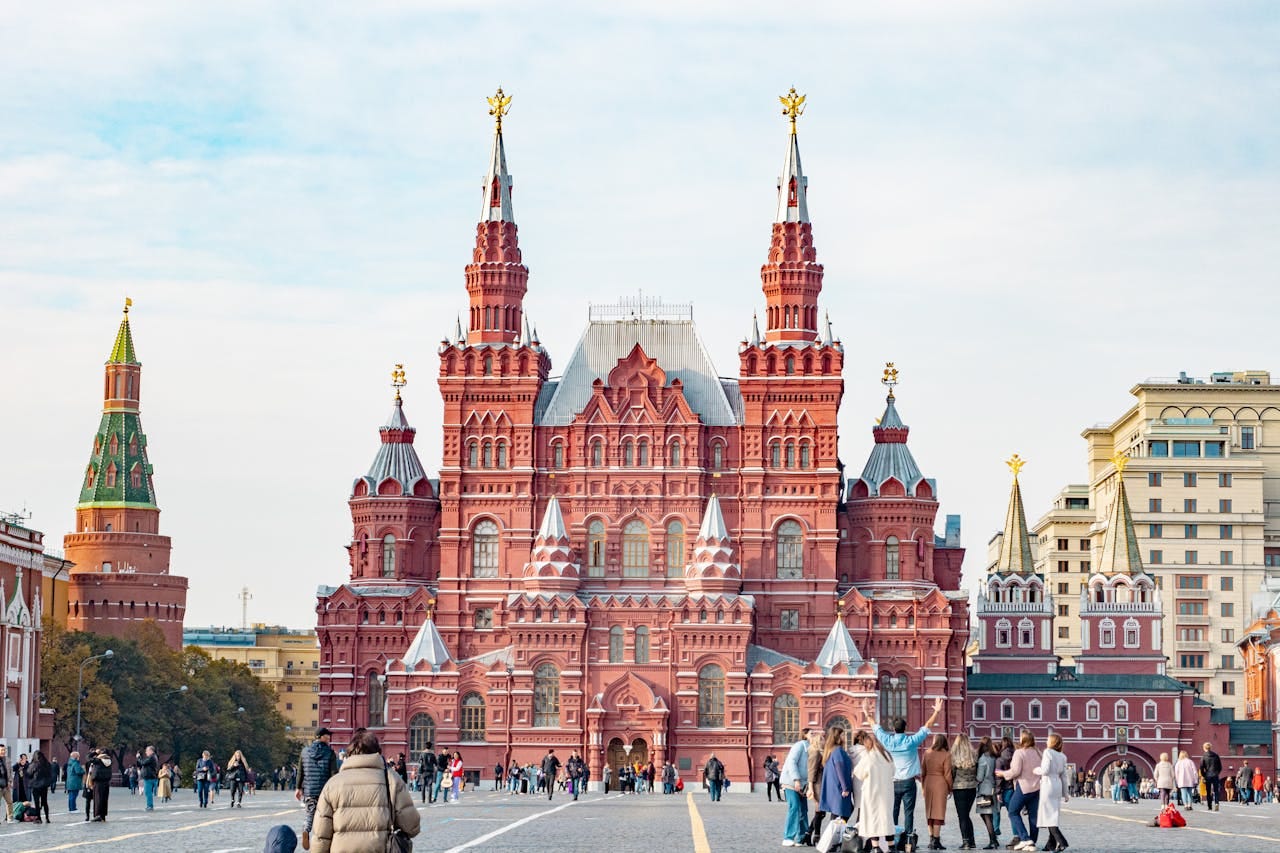

Karl Richter visits Moscow and challenges Western narratives about wartime Russia.

AfD Bundestag1 member Markus Frohnmaier is being accused of “treason” by circles within the Christian Democratic Union (CDU). He is planning a trip to Moscow and intends to seek a “dialogue” there — a long-overdue and eminently sensible initiative. But: in the middle of the war in Ukraine — a war largely instigated by the West and still being kept simmering by every conceivable means — naturally that is unacceptable. The CDU’s hypocrisy belongs to that category where you cannot swallow as much as you want to vomit. There has simply never been greater treason against the German people than what the CDU has done to them since the founding of the Federal Republic.

Frohnmaier wants to go to Moscow; I have just returned from there. After years of absence it was long overdue, and despite the media smear campaigns, travel to Russia is neither impossible nor forbidden. After three and a half years of war, I wanted to see for myself how the country that, according to Western propaganda, is on the verge of collapse and internationally isolated, is coping. I also wanted to test one thing: are we, as Germans, hated by Russians because of the unbelievably foolish and wildly dangerous policies of our rulers?

The short answer: no — not at all. Ordinary Russians you meet in an elevator, a restaurant, or a supermarket, and who learn that you come from Germany, apparently, like their government, know how to distinguish between the German people and their dangerously irresponsible government, whose Russia-bashing is terrifying. On the contrary, respect for Germans remains high; anyone with relatives in Germany or who has been there will gladly show it and scrape together a few friendly words of German. Even at the airport, the stern-faced staff checking passports and tickets bid me farewell with a hearty “Auf Wiedersehen!”

That is not to say that the war is not real. On arrival in Samara on the Volga, there was a drone alarm; later it became clear that such alerts are part of everyday life. But they arrive only as warning text messages on cell phones. In people’s everyday reality, the war is barely felt; life goes on. Were it not for the patriotic “Z” stickers on some city buses and the large posters recruiting for service in the armed forces — with seven-figure ruble offers — one could almost take the war for an illusion. It is apparent that the government does not want to exaggerate it and is keen to avoid imposing hardships on the population. Nonetheless, it feels compelled to raise value-added tax from 20 to 22 percent as of 1 January 2026 to finance defense costs.

The philosopher and geopolitician Alexander Dugin once observed that for many conservatives in the West, Russia embodies an idealized image of a former, “better” Europe that the modern West has largely abandoned, while Russia — officially, too — sees itself as the guardian of Europe’s true, traditional values. Indeed, public life can seem paradisiacally relaxed to jaded Western Europeans, in Moscow no less than in distant Novosibirsk. TV commercials largely show only White people. In Samara, I saw one Black person; in Moscow three. And apparently no one need fear being stabbed on the subway or pushed onto the tracks. By contrast, in the “best Germany there has ever been” (German President Steinmeier) some eighty knife crimes are committed on average each day. One should not glorify anything. Still, the risk of being stabbed is a hard indicator of quality of life.

Dugin has rightly criticized the Russian wartime society — for which the war, all things considered, feels remote — arguing that, despite the West’s open hostility, the country, even in the fourth year of war, has done too little to rediscover its own identity and still often behaves like a copy of earlier Western societies. That is true. On television — apart from a channel or two showing Russian folk music or patriotic war films — there is the same trash as at home: early-evening comedies and pop music. Supermarkets carry everything, and aside from prominent firms like Daimler and Microsoft, which bowed to sanctions, Western products from Nivea to Spaten beer to Apple computers remain ubiquitous. Even in banks, despite decoupling from the Western SWIFT payment system, staff still work on Dell computers. The long-announced “liberation” from American software and hardware evidently has not materialized. Only on the streets do you now see more Chinese car models alongside Hyundai and Daihatsu.

Economic dynamism is visible everywhere. That Vladimir Putin is the central guarantor of the upswing — he celebrated his 73rd birthday just days ago — is beyond doubt for my Russian interlocutors. One of them, Valeri Voronin, long-time foreign representative of the LDPR,2 regards the Kremlin leader as by far the most competent head of state worldwide, a man who in twenty-five years of rule achieved phenomenal things and restored his country’s standing. Anyone who remembers Russia in the 1990s will agree. The war since 2022 has not seriously jeopardized the upswing; on the contrary.

With the sanctions, Western governments have mainly harmed their own populations. In Germany, household energy prices rose by a full 50.3 percent between 2020 and 2024. This is not Kremlin propaganda: the Federal Statistical Office published the figure in a press release. Those responsible for this disaster sit in Berlin and Brussels, not in Moscow.

Russian society today resembles a parallel society. It need not hide from the West, and certainly not from the federal German “shithole society.” Perhaps, in the course of the ongoing confrontation with the West, it will become even more “Russian” — or more Eurasian — in the coming years. Airports now display Chinese signage alongside Russian and English. Undoubtedly, the West’s self-destructive sanctions have accelerated integration within the Eurasian space and the multipolarization of international politics. Moreover, further regional power centers will likely emerge in the near future — Dugin predicts no fewer than twelve in Eurasian Mission, five of them in Asia alone — driven by the economic dynamism of the non-Western world (BRICS!). The rest is ensured by the West’s short-sighted policies as it claws and scratches against its own decline.

On the communications front, multipolarization has already produced hard facts. Not only does the EU censor Russian media and deny licences to Russian broadcasters like RT and Sputnik; Russian censorship is no joke either and has blocked German outlets — even relatively harmless ones like Die Welt — from the Russian internet. For intellectually productive people dependent on a free flow of information, this is as unacceptable as EU heavy-handedness. A VPN helps on both sides. In short: the EU’s ritual professions of commitment to press freedom are a farce. On “managed democracy,” the West has no grounds to lecture Russia. My Russian interlocutors have also noticed that in Germany unwanted candidates — as in North Rhine-Westphalia’s recent municipal elections — are repeatedly excluded from ballots and that there is open movement towards banning the largest opposition party [the AfD].

When, after two weeks, the glass door of passport control closes behind me at Munich airport, I have a bad feeling. Suddenly everything is back: fully veiled women, Black people, Antifa freaks with blue hair. No, I do not want this “value-based West.” I do not accept it. If I were offered an opportunity for treason against the homeland like AfD deputy Markus Frohnmaier, I would not hesitate.

(Translated from the German)

Translator’s note (TN): German parliament.

TN: The LDPR (Liberal Democratic Party of Russia) is a nationalist and right-wing populist party founded by Vladimir Zhirinovsky in 1991, known for its strong pro-Russian, imperial, and anti-Western stance.

Excellent piece. Your observations from Moscow cut through the Western caricature and recall deeper rhythms in Russian history. The pattern you describe, of a nation calm under external pressure and turning adversity into renewal, has parallels in earlier eras. After the Napoleonic invasion in 1812, Russia rebuilt stronger and more self-aware. After the turmoil of the 1990s, it likewise re-emerged with a clearer sense of purpose. In each case, outside attempts to isolate or “reform” Russia only reinforced its internal cohesion and civilizational identity. What the West misreads as passivity is in fact a patient, almost geological form of resilience, one that sees history as cyclical, not terminal. Your essay captures that parallel world vividly.

I suggest you go where your mouth is.