The Synchronicity of Art and Science

When creation becomes a shared language of truth and beauty

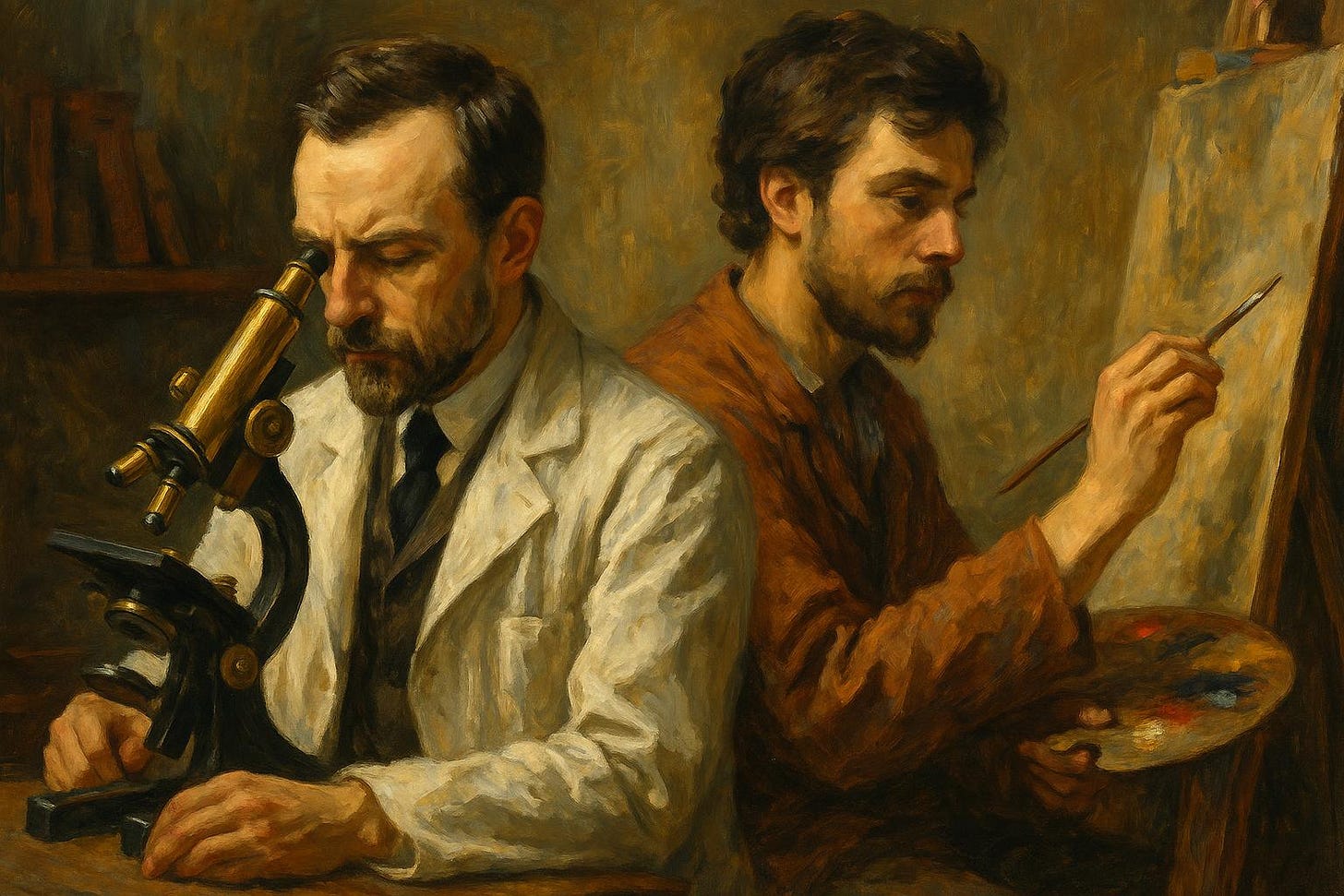

Chōkōdō Shujin reveals that scientists and artists, though often seen as opposites, share the same creative fire.

There are indeed artists who understand and appreciate science. Likewise, there are surely many scientists who enjoy and take pleasure in art. However, some artists seem to harbor a certain antipathy towards science, or perhaps even a certain resentment. Many scientists, similarly, seem to be indifferent or even rather hostile towards art. Some even believe that loving art is a sign of degradation or shame for a scientist, and there are even rare instances of fastidious prudence who immediately associate the word “art” with frivolity.

Are the realm of the scientist and the world of the artist truly so incompatible? This has been my longstanding question.

In the Meiji era, Sōseki Natsume once gave a lecture suggesting that scientists and artists share a commonality in that they can perfectly align their profession with their personal inclinations. Of course, just as artists must sometimes work to earn a living, scientists too must occasionally exert themselves on tasks contrary to their inclinations for the same purpose. Yet even in such cases, it seems not uncommon for them to encounter their innate inclinations within that work, gradually forgetting that it is work, and entering a state of selflessness.

How much more so, then, does such a transcendent state exist for artists and scientists who are not burdened to toil for sustenance or overwhelmed by menial tasks? Examining the special mental state that they experience when immersed in their respective creations and research seems to reveal no discernible difference between the two. But if that were all, this might not be limited solely to artists and scientists. The subtle pleasure experienced by a natural-born hunter in the moment of felling his prey, for instance, or the instinctive satisfaction felt by a martial artist when striking a keen blow, cannot be said to lack points of similarity.

Yet, the lifeblood of both scientists and artists is creation. Just as blindly imitating another man’s art does not constitute the creation of one’s own art, simply repeating someone else’s research is not true research for a scientist. Obviously, there are incomparable differences in the subject matter that the two groups deal with, but there are also considerable commonalities. The subject of a scientist’s research is natural phenomena, and they seek to discover some unknown fact within them and learn new insights that have yet to be discovered. The mission of the artist may be diverse, but it is beyond doubt that within it lies the quest for something new in the broad sense—a new way of perceiving natural phenomena, and a new method of artistically expressing these impressions.

Moreover, just as a scientist, upon encountering a new fact, remains utterly indifferent to its practical value and strives to probe it to its very depths, so too, when a pure artist encounters a novel observation or insight, he will attempt a profound depiction or expression of this observation without any regard to its practical value. The beauty of pure art lies precisely in its lack of utility. Just as many scientists throughout history have become targets of persecution and ridicule for this very reason, artists too have often incurred public resentment, if not sunk into wretched destitution. Were such a scientist and artist ever to meet and lay bare their hearts to one another, they would likely exchange sympathetic words without hesitation. Their goal is the same half of the truth.

Many in the world seem unaware that scientists often derive a certain aesthetic pleasure from their work. However, it is true that scientists have a particular aesthetic life that non-scientists cannot appreciate. For example, the numerous mathematical systems constructed throughout history are perhaps some of the most impressive of all human creations, considering that the harmonious beauty of their consistency often mimic what is found in great art. The various laws of physics, and indeed the harmonious universal facts discovered within biological phenomena, frequently stimulate our sense of aesthetics beyond mere intellectual satisfaction.

When Newton discovered that the seemingly incomprehensible motions of celestial bodies could be unified under the simple law of gravity into an orderly system, it must have been as Voltaire wrote: the voice of the divine echoed, chaos vanished, the deep mysteries of nature hidden in darkness had their curtains drawn back, and the crystalline heavens appeared before his eyes. Voigt, at the outset of his crystalline physics, likened the beauty of crystalline order to an orchestra. Pascal described beauty as a harmonious relation between something in our nature and the quality of the object which delights us. Moreover, regarding Fibonacci sequences that naturally arise, for example, in sunflowers, even without knowing that these are numerical sequences, one cannot help but be intoxicated by a certain kind of beauty. This kind of aesthetic sensibility seems fundamentally similar to that which arises from, say, magnificent architecture or sublime music.

Personally, I believe that artists must possess observational skills and an analytical mind at least equal to, if not surpassing, those required of scientists. This may be something many artists themselves are unaware of, yet the fact remains that it must be so. For any fantastical or dreamlike creation, its foundation must lie in the mental act of dissecting complex phenomena into their constituent elements through keen observation. Without this, depicting a single leaf or blade of grass, or describing a single event or object, would be impossible. And is it not precisely this observation, this analysis, and the manner in which the results are expressed, that determines a work’s artistic value?

Some may regard science as being firmly grounded in reality, while considering most art as pertaining to imagination or ideals, yet this distinction is not entirely clear. Just as science cannot exist without hypotheses in the broadest sense, imagination that is separate from reality in the strict sense is impossible. It is self-evident, even without the aid of philosophers, that the scientific systems constructed by scientists are ultimately architectural creations built within the human mind, rather than reality itself. Formulas and equations are not physical objects, to put it quite simply; they are representations of natural phenomenon. Conversely, however fantastical the creations of artists may be, they are all, in a broad sense, expressions of reality and descriptions of the laws of nature. Art is representational.

There is a common expression, “pure fantasy,” but even within respectable science, if one scrutinizes rigorously, one finds countless instances of what might be called pure fantasy. If the provisional hypotheses used in scientific theories need not precisely correspond with reality, then such so-called pure fantasy is not falsehood at all. If it is not strange to consider an object composed of molecular aggregates as a continuum and apply differential equations to it, then there is no falsehood whatsoever in representing physical phenomena by arranging colors and lines. If, for example, the letters X, Y, or Z can represent certain numbers in an equation, what then is so absurd about utilizing symbolism in art?

Some might go further and say that science is objective, while art is subjective. Yet this distinction cannot be made so simply with words. Objectivity in the sense of being universal to all people does not necessarily apply to all of science. As science advances, the various concepts that it handles gradually recede from our own five senses. Consequently, they become increasingly distant from the ordinary person’s notion of objectivity, tending instead towards the subjectivity of a specialized class of individuals: scientists. If the trend in modern theoretical physics, as some suggest, lies in the gradual removal of anthropomorphic elements, then the result is, on one hand, highly objective, while on another, it cannot be said to be entirely subjective. This bears some resemblance to Cubism and Futurism in the art world, which attempted to express concepts detached from direct sensory impressions.

Next, in natural science, the value of the objects studied is not an issue, but the academic value of its research results and methods naturally has other standards. In art for art’s sake, it is the artistic value of the work itself, rather than the value of the subject matter it treats, that becomes the issue. And just as the value of the latter is a difficult problem, the value of the former is also, strictly speaking, difficult to define.

Scientific rules and facts can be expressed regardless of the specific language or equations that are chosen to articulate them. Yet in art, it might be said – though perhaps not quite so easily articulated – that the method of expression matters far more than the objects themselves. However, this is also not entirely straightforward. It is certainly true that translating scientific principles into Japanese, English, Latin, or German makes no difference, but the principles themselves are a way of expressing natural phenomena, rather than the facts themselves. Simply because the things to be expressed are relatively simple, not only are there not a variety of ways to express them, but there is also not necessarily only one.

Conversely, what art seeks to express is not the object itself, but the “something” that the artist himself seeks to express. However, the means of expressing that “something” are not uniform, and the language is obviously far from consistent. Yet, if we must, it is possible to say that a work of art is the expression of a fact expressed in certain forms or images.

Then, can the botanist’s sketches of plants or the geographer’s landscape sketches be described as works of art? Of course not, as any artist would say. Why is this? Because the mere expression of facts without interpretation does not necessarily constitute art. The subject that the artist seeks to express is entirely different. A scientist’s depiction captures a certain, specific aspect of facts concerning animal, vegetable, or mineral, whereas an artist seeks to portray a facet of something far more complex. Animals, vegetables, and minerals are merely symbols used to express this ineffable “something.”

However, this elusive, ineffable “something” must not exist solely within the artist’s subjective mind; it must possess a degree of universal existence that can be grasped by those other than the artist himself. Otherwise, the so-called art intended for appreciation by an audience could not be established, and consequently, any criticism of it would undoubtedly become meaningless. I suspect that it would be futile to force this “something” into language or image. Yet I privately hold the belief that this “something” is not so far removed from what scientists call natural facts and laws. Even Einstein, an accomplished violinist, attributed his theory of relativity to what he described as “musical thinking,” that is, intuition, regarding scientific breakthroughs as being akin to artistic compositions that reorder man’s understanding of space and time.

However, delving deeply into such matters is not the purpose of this piece. I merely wish to enumerate a few more congenial aspects shared by scientists and artists.

Both artists and rely on meticulous observation and analysis to depict the natural world accurately or interpretively. This involves breaking down complex realities into understandable components, be it through data or visual elements.

The ability to observe is, of course, absolutely essential for both scientists and artists, but imagination is equally necessary for both, as well. Some people often misunderstand science and regard it as something that is merely solidified by logic and analysis, but this is simply not the case. It is clear that logic and analysis can yield nothing beyond what is already contained within their premises. Relying solely on thesis, without synthesis, much of science would likely struggle to advance even a single step. The task of discovering connections between phenomena that appear at first glance to have no relation, and of organizing disparate facts into a coherent system, relies heavily on the power of imagination.

Furthermore, scientists require a keen intuition. Throughout history, the foremost scientists who made great discoveries and established outstanding theories often first intuitively grasped the outcome before constructing the logical pathway to reach it. Even within the field of mathematics, considered purely analytical, it is said that actual development frequently stems from the intuition of great mathematicians. This intuition is akin to the so-called inspiration of artists, and there are numerous anecdotes concerning scientists in this regard.

A problem that has long defied interpretation may, through a fortuitous occasion, reveal its ultimate solution almost instantaneously, like a flash of lightning. Once the target is illuminated by that flash, it is merely a matter of clearing the logical or experimental path to make it recognizable to anyone. Admittedly, the results of such intuitive recognition are often riddled with error, yet the mental processes at work in these instances among scientists share considerable common ground with those experienced by artists when struck by divine inspiration. According to accounts by his contemporaries, Newton was sitting beneath an apple tree when an apple fell, prompting him to wonder why it fell to the ground, rather than sideways or upwards.

Thus, the colors, harmonies, melodies, dramatizations, and events that artists employ to express their divinely inspired impressions are, so to speak, akin to the artist’s logical analysis. Similarly, the logical analysis by which scientists establish their intuitively gained revelations should, in a sense, be regarded as the scientist’s technique. However, such intuitive masterpieces are not easily achieved by scientists. Before attaining them, constant, faithful effort is required. One must diligently engage with nature and persistently scrutinize facts. It is crucial to pay attention to subtle phenomena overlooked by ordinary people and first make accurate sketches of them. In this way, while immersed in seemingly utterly mundane events, a great idea may suddenly flash into existence.

Among scientists, there may be those who regard the faithful creation of individual sketches as the scientist’s primary duty, dismissing all synthetic thought as purely speculative and rejecting it outright. Conversely, others might scorn these minute sketches as worthless. Yet if the fundamental purpose of science lies in systematizing knowledge or economizing thought, the ideal would be to gather these sketches, use them as a foundation, and assemble a grand structure, establishing a coherent system. I believe the very same principle applies to art.

In Hideo Kobayashi’s writings, there is a passage suggesting that novels and plays are akin to ethical experiments. Indeed, for instance, the so-called thought experiments constantly employed in theoretical physics are, in a sense, entirely physical fiction. The process of deducing the progression of phenomena under abstract conditions that no one has ever tested and which are unlikely to be realized in the future, based on known laws, and then using this to arrive at other laws, could arguably be said to be more fictional than fiction itself. The significant distinction lies in the fact that, whereas in fiction the laws are often so complex that the deductive outcome is not unambiguous and unique, with multiple possible solutions, in science there is invariably only one.

Regardless, the mental process at work when a novelist creates fictional characters and dramatizes the unfolding events between them seems remarkably similar to that of a scientist abstracting matter and energy to deduce the pathways phenomena should take. At the very least, scientists of this sort have no right to seize a novelist and denounce him as lacking analytical prowess. Certain novels and plays may be mystical or fantastical, far removed from reality. Yet for such works to stand as literary creations, they must not disregard certain principles that naturally exists within the reader’s mind. Should any work ignore this principle, it would be nothing but the literature of an insane asylum.

Artists and scientists often share certain weaknesses as a consequence of their profound attachment to their respective arts and sciences. One such weakness is narrow-mindedness. While this may occasionally arise from base material interests, which is a separate matter, the common affliction among scientists and artists is a lack of tolerance for others, leading them to bitterly exclude one another. This too may be seen as an example illustrating the common ground in their psyches.

Ultimately, if narrow-mindedness and jealousy represent the flip side of obsession, this may reveal how profoundly the love of art and science burrows into the depths of the human heart. Upon reflection, it seems paradoxically puzzling that scientists, at least, should not necessarily embody the broad-mindedness and impartiality one might expect from the very nature of their discipline. Yet, upon closer consideration, it appears both scientists and artists inherently possess, in another aspect, the qualities of a certain egocentrism. This may be regrettable, or perhaps it is simply an irresistible phenomenon of nature. From one perspective, the fact that both often expose this weakness and, consequently, have no time to consider the interests of the resulting outcomes, may at least express a serious passion common to both.

Whether scientists and artists exist in separate worlds, indifferent to one another, or even regard each other with hostility, this may not be particularly significant. It would hardly pose an active impediment to the development of science or art, respectively. Yet, viewed from the standpoint of a third party detached from these two worlds, these two classes appear to be surprisingly close, like blood relatives.

A Respectful Reflection: Why Art Ultimately Stands Above Science

Thank you for this wonderful and thought-provoking essay.

It is rare to see such a sensitive and intellectually generous exploration of the relationship between science and art. Your effort to highlight their shared processes —intuition, observation, imagination, and the pursuit of something new— is admirable and refreshing.

That said, I would like to offer a friendly counter-perspective, written with the same spirit of respect and appreciation that your article embodies.

I agree wholeheartedly that science and art share many psychological processes. Both require imagination, both demand discipline, and both can lead their practitioners into states of immersion and selflessness. And yet, despite these similarities, I believe that art ultimately occupies a higher ground than science —not in value, but in nature.

Here is why, as gently as I can put it:

1. Science describes what already exists; art creates what does not.

A scientific theory is an interpretation of external reality.

A work of art is the birth of a new reality.

The scientist discovers; the artist invents.

In that sense, creation reaches deeper than discovery.

2. Science is dependent on external verification; art is complete in itself.

The scientist must prove his intuition to the world.

The artist does not need to prove anything.

A poem, a painting, a piece of music is whole and valid by its mere existence.

3. Science requires tools; art only requires the human being.

Every scientific advance needs instruments, funding, technique, or infrastructure.

A great work of art can arise from nothing but the inner life of a person —a gesture, a word, a line.

4. Science changes the external world; art changes the inner world.

Science modifies our environment.

Art transforms consciousness.

One is utilitarian; the other is civilizational.

5. Science is temporal; art is timeless.

Every scientific theory is eventually replaced.

Newton, brilliant as he was, was surpassed.

Einstein will be surpassed.

Yet Homer, Bach, Shakespeare, or Goya never expire.

Their truths remain alive.

6. Science often needs the support of art; art does not need science to exist.

Even Einstein invoked “musical thinking” and aesthetic harmony as the foundation of his discoveries.

Science frequently borrows metaphors, symbols, images, and intuitions from the artistic realm.

Art stands independently.

Thank you again for writing it. It is a pleasure to engage with ideas expressed with such clarity and sensitivity.

Not convincing at all as it treats both art and science as a lumpen mass, which they are not.

Chartres cathedral is not a photcopy of a can of campbells soup. A bridge spanning a vast gorge as we see today in China, is not a toxic drug produced for no other purpose than to make money.

Modern art has nothing of the sacred in it, nor does modern science. This clumsy piece is clueless in relation to this fundamental distinction.