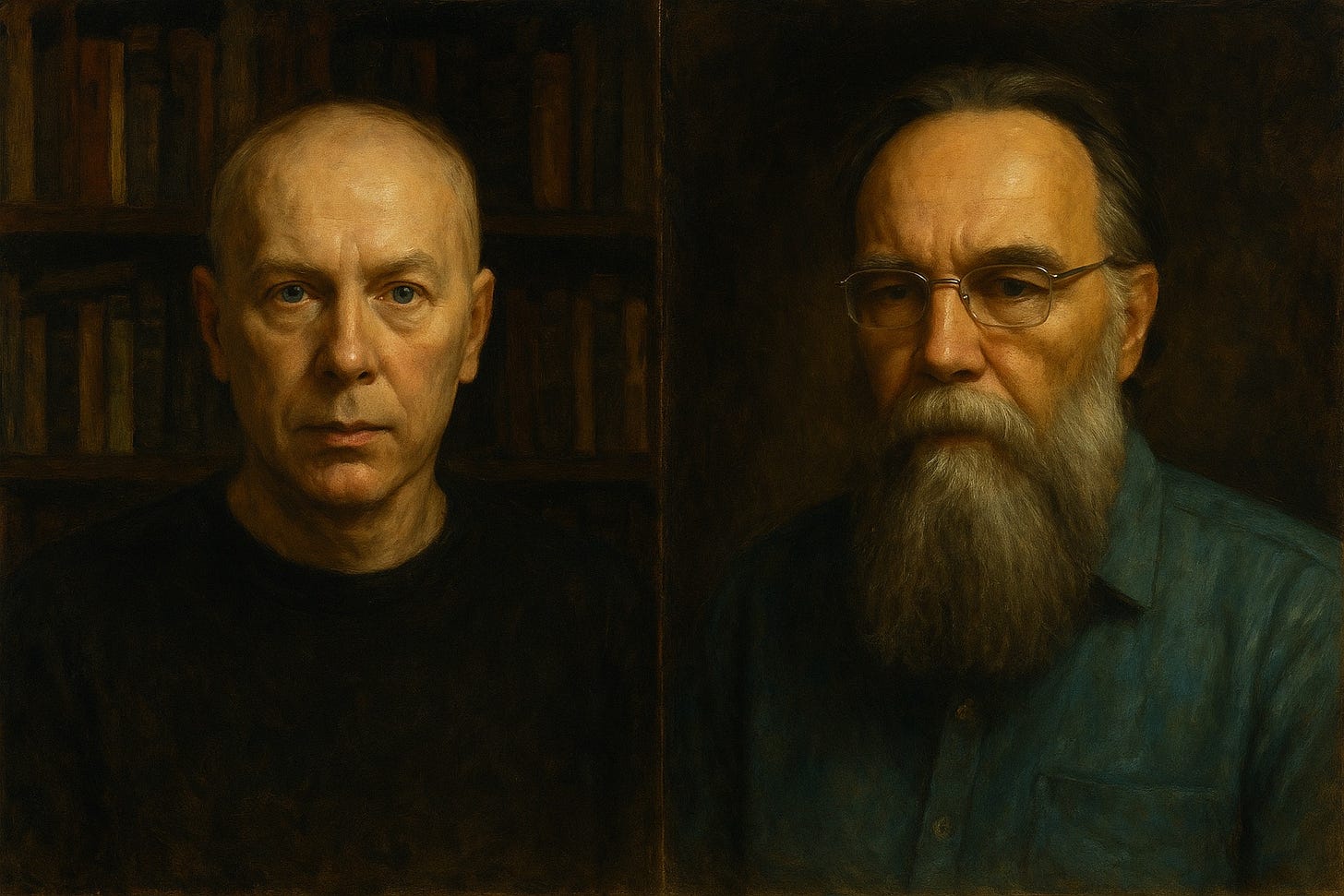

Nick Land and Alexander Dugin on Liberalism, Empire, and the Eschaton

On Dasein, decentralization, and modernity’s occult return

This is a transcript of Auron MacIntyre hosting Nick Land and Alexander Dugin in a wide-ranging dialogue on liberalism’s Anglo roots and “paleoliberalism,” the “Empty Summit” (decentralization) versus republican overcoding, empire and sacred politics, plural Daseins and temporalities, eschatology, and whether modern tech/AI and recent “Satanism” accusations signal a religious return rather than simple secular drift.

Watch the debate here.

Auron MacIntyre:

Hey everybody, how’s it going? Thanks for joining me this afternoon. I’ve got a great stream with some great guests that I think you’re really going to enjoy. I’ve had the pleasure of interviewing both of these men previously, Alexander Dugin and Nick Land. I think both are critical thinkers in our world today, some of the few people doing very interesting philosophy, and I’m excited to have both of them on for the discussion. So Nick and Professor Dugin, thank you so much for coming on.

Nick Land:

Great to be here with you both.

Alexander Dugin:

Thank you. Thank you very much.

Auron MacIntyre:

Absolutely. So we’re going to get deep into this, guys. There’s so much to talk about. I think we’re going to talk about accelerationism, angels, the possibility of liberalism, an extension of the Anglo way of being. But before we get to all of that, we need to hear from today’s sponsor. Everyone knows that college is a major investment, so it’s really important to do your research. You want to find a school that shares your values, but who has the time to dig through all those college websites? Well, today I’ve got great news for you.

There’s a free, easy-to-use resource that does the work for you. It’s called ChristianCollegeGuide.com. This online directory of over 250 Christian colleges and universities is a one-stop shop. ChristianCollegeGuide.com lists all the basics such as acceptance rates, tuition costs, and academic majors. But here’s what makes this resource truly special. ChristianCollegeGuide.com will show you the school’s faith commitments, its campus policies, and its spiritual life.

All the info that you will need to find the college you can trust. This is the definitive college guide for Christian higher education. And it’s completely free. So if you or someone you know is considering college, go to ChristianCollegeGuide.com to create a free user profile and start today. It’s ChristianCollegeGuide.com.

All right, guys, before we get started, I just want to remind the listeners that this is a pre-recorded episode. Obviously, I’ve got to coordinate this across literally the entire globe so we can have this discussion.

So we had to do it at a weird time. So, unfortunately, we will not be able to take any questions at the end. So, gentlemen, I’m just gonna kind of try to guide this discussion, obviously mainly want to hear from the two of you, so I’ll just have some prompting questions, but feel free to step in, ask questions, interact. This is by no means some kind of formal debate or anything of that nature, but I’ll just open with, I think, what is probably an easy, common area of agreement and see kind of where the conversation develops from there.

So, I think both of you have discussed liberalism as an outgrowth of kind of the Anglo way of being as a specific strain of this cultural development that has grown into a more global ideology. In some ways, some people might think that’s good.

Some people might think that is deleterious, but maybe we can just open up with this basic idea. Mr. Land, can you talk a little bit about liberalism and its Anglo roots and what it’s kind of become as it’s been abstracted out of that particular way of being?

Nick Land:

Well, the first thing I would say, I’d start with a point of agreement in the sense that I think what we call liberalism now as this globalist, universalist, moralistic monster is obviously the greatest problem in the world.

And so that’s something I’m entirely confident about. Where I think that I will probably be disagreeing is that I don’t think that this historical outcome is something that’s strictly inherent to liberalism.

And I think there is a defensible notion of liberalism, paleoliberalism that can be essentially defined in a way that is very, very different to what it has predominantly, what the things that have predominantly happened in its name.

And I mean, I have a little spiel on that, but I think maybe I should sort of pause and hesitate and, you know, allow the counter position to be stated first.

Auron MacIntyre:

Absolutely. So, Mr. Dugin, do you believe that there is a version of liberalism that can be healthy, that can be operated in the service of the people it was meant to serve?

Nick Land:

Can I just interrupt, just for one thing, just to say that it can be healthy for the English people. I mean, you know, so I totally am not making a claim that even in the most stripped down, paleo form, this is something that is the basis for a global ideology.

That is not at all my claim. That rather is a point of disagreement. So, yes, sorry.

Alexander Dugin:

So, thank you. We could discuss, we could touch the subject from different angles. First of all, I fully agree that liberalism is an Anglo-Saxon phenomenon. We need to make a kind of geology of liberalism. It started from Britain and I don’t think that always Britain was liberal.

So, that was a kind of some historical moment when British people, English people, they turned into this ideology. And we did, if we delve a little deeper, we could see, we could trace a kind of genealogy of liberalism. And what is liberalism?

Liberalism is the identification of the human with the individual. That is a kind of absolute individualism that wants to liberate the human being from all kind of collective identity, from personality. So individual is kind of opposite to personality.

Individualism is something that you don’t share with anybody. So, that is true individual, the individual core. So, you are absolutely yourself and nothing else. You don’t share your identity with the class, with the estate, with the church, with the race, with the ethnic.

So you are absolutely, absolutely reduced to be what you are and nothing else. So it is a kind of liberation. So individualism and liberalism are very linked, in my opinion, because liberalism is a kind of project. It is a historical project, a scenario, a strategy to liberate individual from any kind of collective identity.

And that started, historically, not with Anglo-Saxons, that started with nominalism in France, in Roscelin, that started with Franciscan order in Italy, but it has arrived, it has arrived to England with the same Franciscan order, monastic order, and was kind of accepted by the people, by Duns Scotus, by Ockham, Franciscans themselves.

And that has prepared the earth, the territory for the appearance of the Protestant anthropology based on the individual relations to God. So that was a kind of process, process of some very special development of theology, of Western Christian theology, that has led to this conclusion, to this liberalism.

And the matrix of most active development of that was Reformation, Great Britain during Reformation.

And after that, that was, as Mr. Land has described very correctly in his blog, that was a secularization of Protestantism. So, of Calvinism, Calvinism, Protestantism. So, after that was the kind of capitalistic secularization of the same individualism. First, religious and theological, and after that secular.

So, capitalism, according to Max Weber, and according to your analysis as well, was as well a kind of application of this theological anthropological rule to the whole system of the society, of economy. So, in that sense, it is a bit pre-Anglo-Saxon because before, before this domination of empirical nominalist attitude, the English theology was different.

Anselm of Canterbury and the other, you had many Platonists, Aristotelians and different kind. Nominalism is something different because according to Plato, according to Aristotle, the man is something more, much more than individual. So only to individualistic nominalist, Roscelin-Ockham version, the human being is individual.

So that didn’t start with Anglo-Saxons, but that has flourished thanks to Anglo-Saxon tradition and that was a kind that became, at the same time, a feature of the Anglo-Saxon identity as well, projected on the United States as well, but at the same time, step by step, it became a kind of global universal pattern, recently, recently, because continental French-German tradition fought against this until recently. So, now it is a kind of universal, global norm. So, if the man is individual, and that is out of the discussion.

So, when this Anglo-Saxon philosophical concept became universal one, all the contradictions included in it became open as well. So now, if we compare the old English high style, very ethnically limited understanding, exclusive aristocratic understanding of liberalism.

If we compare that with this globalist, very vulgar, mass version of liberalism, we could have a shock because comparing this paradigm that was ethnically marked with this, the process of globalization, of massification.

First of all, the United States, it gives the very special image of all that. So that is the kind of terminal station. So you started with something more or less noble, more or less interesting, stylish, I would say, and you have arrived to some parody, to something that is totally abhorrent.

So, in that sense, I could agree with Mr. Land’s concept that there is different phases if we compare them. So, we see the huge difference, the abyss between them because a gentleman, British gentleman, proposing himself as individual and something totally independent is one thing. You can find very literary good examples of how it works.

So, that is something very high and stylish. So, you could bear your identity as Englishmen did in the history and the culture. And now when we distribute that among all the population, that is a parody. That is something extremely, extremely awkward.

That’s horrible. That is the kind of, that inspires the kind of, kind of the sense of, we deal with something, with something shameful, with something completely opposite to the beauty, to the dignity. So we should not distribute that among everybody else.

And being localized, this individualistic attitude, being put in the normal limits, it could be very sympathetic and attractive. But projected on the global level, it seems horrible.

Nick Land:

For sure. I think maybe we get onto the whole globalized side of it for sure. And it’s where everyone here is beginning in terms of the problems that they’re facing and contemporary politics.

I mean, there’s two immediate responses that I would make to what you’ve just said. One, very quick, which is just to say, at the anthropological level, I think one of the most fascinating and persuasive bases for this seems the work of Emmanuel Todd on family structure, where he has different family categories and says that the basic ideological tendencies of different people are very explicable on the basis of their kind of normal family type.

And one of his family types is what he calls the absolute nuclear family. And it’s very restrictive. It’s basically English and Dutch. And he says that this is associated culturally with tendencies to liberalism in what we would now call libertarian variety.

So I think, you know, I’m saying, this is just to say, I think people are different and, you know, just underscoring this thing that this is, I think, an English problem initially and it becomes a completely other type of problem when it becomes globalized and generalized as a pattern for all human societies.

To just stick to the, I’m not saying Emmanuel Todd is the alpha and omega of this question, but he brings out the absurdity of that globalistic project of that it’s implicitly saying all the peoples of the world should pattern their social existence as if they had an Anglo-Dutch family structure. I mean, it’s ultimately a nonsensical, an unsustainable, an absurd assumption, an assertion that, seen in those terms, of course cannot lead anywhere good.

And the second thing I’ll say is individualism, I think, for sure is crucial, but it has different aspects to it. And I think that aspect that is truly crucial, and which ties up with the theological structure of paleoliberalism, which I 100% agree is Protestant, you know, I talk consistently about the Anglo-Protestant Whig tradition, an ethnicity, a religion, and an ideology, and they, all three of those are the same thing seen from different positions. And the way into this, because I think that there’s been this bizarre amount of Satanism discussion recently.

And so, I thought, I know this is a text that is very important to Professor Dugin, which is in Faust, Part I, I think the Faustian spirit is very much part of this discussion, where Faust summons Mephistopheles and asks him, who are you? And Mephistopheles says, “Ein Teil von jener Kraft, die stets das Böse will und stets das Gute schafft.”

A portion of that power, which always works for evil and effects the good, which always wants evil, which always works for evil and always creates the good. So that’s Goethe’s. If you say, well, what is Satanism? And that’s Goethe’s answer to that.

I think it’s very interesting. Mandeville’s, the consolidation of paleoliberalism in England really takes place in the Scottish environment. Perhaps the single most perfect distillation of it is found in Mandeville’s The Fable of the Bees, which I don’t think I can summarize very easily with a quote.

I think it’s just to say he goes on to influence Adam Smith and if I could just a very quick citation from The Wealth of Nations where Smith says he generally, and he means the individual, it’s actually said before, every individual,

“He generally indeed neither intends to promote the public interest, nor knows how much he is promoting it. By preferring the support of domestic than foreign industry, he intends only his own security, and by directing that industry in such a manner as its produce may be of the greatest value, he intends only his own gain. And he is in this, as in many other cases, led by an invisible hand to promote an end which was no part of his intention.”

And that, to me, is the essential ideological aspect of individualism, as it relates to paleoliberalism.

That’s to say, the fundamental assumption is that there is an empty position, what I call the Empty Summit, which would be an instantiated public morality and instead that function is delegated to the invisible hands.

I will insist on pluralizing it. The invisible hands are the key theological and economic and, you know, maybe in a sense even ethnic axis on which paleoliberalism determines itself. And there are huge consequences to that. I mean, maybe you should just at this point just stop there to say, you know, that Mephistopheles’ speech and Adam Smith’s statement on the invisible hand are almost identical.

They’re both saying that the common good is not a deliberate intention at the level of the individual, and it creates the good because of a higher power, because of the fact that it’s guided by this religious axis, the Empty Summit, the fact that there is to some degree at least massive constriction and delimitation of what would be an authoritative public moral authority. So that to me that’s what paleoliberalism is. That that is not at all what I think we’re seeing now among people who call themselves liberals.

Yeah, okay, I should pause at that moment.

Alexander Dugin:

Right, right, very interesting, very, very pertinent point. So, if we prolong a bit this comparison between Faust and Mephistopheles and Adam Smith, we see a kind of Ophitic understanding or Gnostic Ophites who have revised the kind of the role of the evil in the history.

So, the history, the role of the history in the evil was misinterpreted according to Gnostics. So, it was always wanted, it has always wanted to make evil or indifference toward the good. And at the same time, that was the kind of introduction of secret way to the good.

So, in that sense, I totally agree with that. So this comparison is absolutely genius, I think, because the capitalism in that Scotland, low church, Calvinist part of Protestantism was something like an evil regarding the common good of community.

So that was a kind of nihilist, nihilistic attitude that finally when it was enlarged and projected on a global level, that has prepared the way to alternative results.

So, the expansion of the evil of individualism, egoism, narcissism, nihilism, has led to some contrary conclusion. So that is very interesting. So that partly was the thought of Karl Marx that the more capitalism will prevail, the more conditions for revolutions, revolution, proletarian revolution, socialism, will be prepared.

And the Marxists, Trotskyists above all, they criticized the kind of Soviet or Chinese will to stop this, to say we have enough of the evil, now we are going to establish some common goods with this prepared terrain of the capitalist, Mephistophelian, demonic expansion.

So let’s stop here and now we are coming to create something really, really good. And that failed in the case of the Soviet Union because we tried to say enough with capitalism but we had not enough of capitalism.

So, we were much more traditional society. So, that was maybe the reason why we have failed with socialist experience. But what is interesting, so in China’s case, capitalism, it considered to be evil that could be turned into the good and because of cultural, I think, identity.

So Chinese society has succeeded in that. So, using Mephistopheles as a kind of horse to bring to the goodness and the prosperity. So, I think that, but nevertheless, the main idea that capitalism is evil and that could bring the good is very, very important, I think.

So we could interpret that with the Marxists or outside of Marxists. We are not obliged to follow them. We could just point out that there is the logic. Very, very close, I think, near to that.

And, but idea to reduce the liberalism to paleoliberalism and to unite it with ethnic Anglo-Saxon ambience, I think that will inscribe very well in the multipolar process if English people, Englishmen prefer to be such, that is your decision, it is your destiny, it is your free will to build your society on the principles you share.

So that is absolutely legitimate case, I think. The other thing, if you oblige the other to follow the same example against their will, that is something completely different, I think.

And so, maybe this idea to reduce the liberalism to its paleo origins, the paleoliberal form, it could be very, very good acceptance in the world, but more exclusivist liberalism is the better for the humanity, I think, and better for Anglo-Saxons, British people as well.

It’s your destiny, it’s your culture, it’s your particular response to the answer or challenge of history and you could defend it, you could insist on that, but when it got outside some normal organic natural limits, it became something different. That is my point.

Nick Land:

Sure, sure. I mean, as a side note on this, I think the Chinese case is very interesting. Because they also have an indigenous cultural matrix that is very comfortable.

You know, it’s I mean the Empty Summit in Chinese culture is nothing like as clearly vividly asserted as it is among Anglo-Saxons but the Dao-legalist tradition has a very strong vein of this, you know, that the best emperor is invisible to society. It’s a very strong notion, and the Cantonese and the coastal sort of mercantile populations very much have this notion, the mountains are high and the emperor is far away.

I mean, it’s this notion that you have a sort of nominal deference to central authority on a massive scale, but its virtue lies precisely in its near-invisibility — its recession from the realm of actual micro-social interaction, and I think that that’s why the Anglos and the Chinese have actually practically always got on with each other very well on this level. I mean they’ve always, they probably both misunderstood each other and in terms of thinking that they were actually sharing the same cultural matrix, that’s not at all something I’m suggesting, but it has enough analogies is that it’s allowed very productive commercial interaction across history and certainly compared to others where obviously the transportation of Anglo-style individualist capitalism has just met vastly more friction and resistance, understandably from cultures where it is entirely an alien imposition.

Alexander Dugin:

I totally agree with your analysis about Chinese culture and what you have said about the Empty Summit. It’s a very important concept. I think that we need to understand that empire, classical empire, sacred empire, was precisely defined by transcendental nature of the summit. So, the summit is not filled with some positive meaning.

It is open. The summit is open. That is the very, very, very natural sacredness. The same with emperor who is high, who is hidden, who is outside. So, the same for the classical, traditional philosophical empire. Empire is ruled by empty space, Empty Summit. Empty Summit is apophatical political concept. That is very, you’re absolutely right about that.

So it should be, it should be how open, open to the spiritual influence, to be open, to be filled by some extra human presence. And that is very functional elements. So, and in my opinion, I have made my suggestions in my x.com account concerning your concept of Cathedral, your and concept of Curtis Yarvin. So I think that maybe the much more correct concept would be for Cathedral Republic.

Republic is something closed on the summit. The summit is totally closed. So, it is purely profane, nothing sacred, no openness to the high, and only self-reliance on the same immanent rational organization.

So, everything great comes from empire, from the political concept, social, philosophical concept with Empty Summit. That is the key element. And to sum up, apophatical top, apophatical head of the political organization makes society open to the presence of transcendent influence.

That is sacredness. And republic is always profane. So, kingdom, monarchy, empire could be sacred. And when you choose the republic, you are closed on the top. So, you put something, you put the mirror on the top. So mirror that should mirror some of these mainstream desires, all these atomistic creatures.

So that is kind of what you have called the other very, very, very genius concept, degenerative ratchet. So degenerative ratchet, it is precisely republic. So, because republic is self-centered, it is closed on the top.

So that is important. So, when we try to save the state, the politics, we should open that. So, we should, through dictatorship, come to the empire. Before republic, there is kingdom, in the Roman case. After the republic comes dictatorship, and after that, the empire.

So, empire is something open, as Virgil has described it. So that is return to Apollo, the return of the vertical line that should, and the place for that, that should be preserved for that. And maybe in the early Protestantism, pre-Protestant region of Wycliffe, for example, or German mystics as Meister Eckhart, they preserved this empty space in the heart of the human heart, in the core of the human heart.

So, this empty space where Christ should be born is a kind of apophatical terrain, domain. So, Empty Summit, I think that is a great concept. So, I agree with that.

Nick Land:

I mean I was thinking that people might need a little a little framing in terms of it seems to me like looking at your work and looking at these questions that there’s two sort of frames that interact and one is actually folded within the other, which is there’s a theological frame and there’s critical German particularly critical philosophy and both of them share an insight that’s very close.

I mean obviously in a way critical philosophy maybe you could say actually secularizes this insight but the theological basis is the fundamental role of the attack on idolatry as being the fundamental gesture of the religious tradition.

That’s to say that an idol is in the place of the divine and the role of the religious process is to strip away those idols.

And you get it obviously right. I mean, Nietzsche’s Twilight of the Idols, you know, he’s still within that tradition and that becomes the critical tradition where in Kant’s version, which leads on the main line to Heidegger, who of course is crucial figure to you, but in Kant’s initial formulation it’s the confusion of an object for the conditions of objectivity.

So transcendental philosophy is trying to recover the conditions of possibility for objectivity from idols of objectivity that have been put in their place.

And I think that you can see that these, the problems with that and its opportunities are also at work in the liberal tradition, I mean probably at work everywhere. And holding open Empty Summits, to formulate it in that way, is very similar gesture.

It’s to take away the idol that is occupying that position that should be the open, transcendental, sacred position that is actually the common religious direction of society. Yeah, I’ll take that as a complete thought.

But no, sorry, I won’t, I won’t take it as a complete thought. At the risk of a slight digression, maybe I can just actually relate it more directly to your work in the sense that it seems to me that your Fourth Political Theory is in this in actually in a double sense Heideggerian. Like it’s Heideggerian because you talk about Heidegger a lot and Heidegger is the key to you to actually kind of organizing what is going to be substantially and positively the Fourth Political Theory.

But it’s also that your work is structured very similar to Heidegger’s in the sense that actually it’s question. You know the structure of the book is a question.

And the substantive work that Heidegger’s doing in terms of eliminating metaphysical ontologies, idols of being, and in terms that are most interesting to you, idols of the human, you too are spending, you know, the substance of the book is clearing away these idols of the position that would be the Fourth Political Theory and to understood correctly the Fourth Political Theory like the question of being for Heidegger is actually a question being posed articulately by your book, not something that can be just understood as another object level claim that you’re proposing some model of politics as a substitute for these idols that you’re wanting to demolish.

And so, I mean, I guess I’m saying on that, do you think that that is a sound approach to what you’re doing in that work and on that line of inquiry?

Alexander Dugin:

You have grasped the very, very core intention of Fourth Political Theory. It is exactly as they would say, it is just the question, it is not the answer. It is clearing, preparing the terrain for something to come. It is open summit concept. So, absolutely, it is liquidation of idols, of the modernity, of political modernity, with this limited liberalism, communism, or nationalism, and a kind of invitation to put the question of the politics in the open.

So, it is questioning, it is not a model.

So when, for example, I have spoken with my friend, a very interesting philosopher and thinker, Alain de Benoist in Moscow 20 years ago, maybe a little less, 20, something like that, we have spoken about what could replace the main figures of the classical political theories, class in Marxism, individual in liberalism, and nation or race in the third political theory. They are, in our opinion, idols.

So, they are just something that is accepted uncritically. That is a closed summit concept. So, you should do that because of class, you should do that because of individual, you should do that because of nation or race. And what could replace that? And we have simultaneously came to the conclusion that we should let this subject to be something indefinite, so something open.

And we agreed with Alain de Benoist about the concept of Dasein, Heideggerian answer. So, the main figure, the subject of the Fourth Political Theory should be Dasein. And that creates a new geometry, a new approach to the field of the politics.

So, we should construct institutions, economies, social relations, basing on existence. Existence before it is shaped as, for example, class or this kind of subjectivity or other class type of subject. So, it is, but this absence of the concrete project is not just defaults, not just something we miss or lack, that is a kind of richness.

So, the Fourth Political Theory is open-end theory. So, it is the concept with open-source theory. So, you could follow all the elements rationally, because it is based on the philosophy, on political philosophy, on the history, and you could combine or try to transcend that, that you can answer this open question as you wish.

So, when I have spoken very interesting elements with a disciple of Heidegger, Professor Hermann in Freiburg. He was his last pupil and follower, and he was the head of the Chair of the Phenomenology in the Freiburg University. And I have said to him, he was very close to Heidegger, to Hermann, that I think that there are multiplicity of Daseins. There is not only one Dasein, human Dasein, but there are so many Daseins as the civilizations, as culture.

He started to think and he said Heidegger would deny that. So, for him, the Dasein was unique and that was the relation to the death. And I have found an argument. But if you consider how death is perceived in Japan, in Russia, in China, in the Western world, in the Islamic world, in India, there are so many different relations to the death.

That is not one universal relation of being to the non-being. So that is culturally defined and he would say you should discuss that with Heidegger, but it is impossible. So, multiplicity of Daseins, that is the principle that we should not have only one Fourth Political Theory, but so many Fourth Political Theories as we have civilizations.

So, I think that this plurality is embedded in the concept of open source. That doesn’t mean that I, as a Russian, know what should be placed on the Empty Summit. No. But our understanding of the absence of something on this Empty Summit is as well Russian.

So, we have our intuitions, our suggestions, our approximation of something that should be put there. And you could have totally different answer to that. So, that is very important to accept Fourth Political Theory, the plurality of the civilizational answers.

Not to impose a new idol. Fourth Political Theory has no name because we try to avoid, to create new idol instead of capitalism, socialism, or nationalism. So, we try to enlarge the field of freedom, I would say.

Nick Land:

I’m wondering whether Auron’s got some questions.

Auron MacIntyre:

Yeah, let me jump in here and just lower everything by a standard deviation. So, both of you gentlemen have, I think, said in your own way that there is a version of liberalism that could be bound and, you know, to its particular ethnos and be, operate in this paleoliberalism and could ultimately be fruitful. I wonder however, if that is entirely true, because, you know, we’ve talked about difference between kind of the modern globalist ideological project as opposed to perhaps a classical empire.

Rome was brought up several times and in one sense, yes of course Rome was a classical empire in that it could not go in and completely change the way of life and ideology and religion of every one of its peoples and therefore had to allow them to operate in their own way. But I wonder if that was more of a choice of ability rather than one of ideology, you know. Famously, they said, Rome created a desert and called it peace.

So, it’s not as if the Romans were not familiar with the idea of imposing their will, their overcode upon any given peoples. And so, the question I think ultimately is, was liberalism simply the ideology that was around when scale met this ability to impose itself globally? Is it the fact that Anglo-liberalism simply was the most successful ideology at the time in which the ability to scale and force a way of life onto the globe happened to be available?

Is it a technological, was it just the ideology that was driving the car when the technology to do this arrived? Or is there something very inherent to liberalism where it must become the idol at the top of the summit? It has no choice, but if it’s going to expand, if it’s going to go through its way of life, must it assume that particular role?

Or is it just a happy accident of the technology catching up with the state of empires at that time?

Nick Land:

I’ll respond quickly to that. Two sort of terms of what could be sort of threads to follow. I mean, the first and most basic one is to say that modernity, and by that, I mean, I don’t mean what we’ve got now. I mean, again, paleomodernity, that’s to say capitalism, technology, modern science, I think are integral to even paleoliberalism.

I mean, I think in the 17th century, the liberalism came together, modern science was initiated, capitalism, I mean, again, you can trace capitalism back to Venice, but industrial capitalism, I think, is English and belongs to the same thing.

The motto of the Royal Society, nullius in verba, I think is again, the Empty Summit. I think it’s like basically a liberal social technology that initiated modern science. So, in that sense, I don’t think there’s a coincidence about it. I think there’s a tragic necessity that this liberal formation unleashed enormous power, technical, military, industrial power, and that that fueled its globalization, and its globalization, as I think we’re all agreed, led to its catastrophic demise.

So, you know, I think that there’s these deep forces of necessity.

And the only other thing, very quickly, I’d say, is I think that there are strands where it persists and where you should look for it is again in social technologies.

Think you know what is the paleoliberalism that persists in the modern world? I think it’s the internet, I think it’s cryptocurrencies, I think it’s AI on the machine learning model to do with distributed neural nets, the model for AI that’s, again, been explosively successful. I think that those are liberal technologies. They require a liberal mindset to do with decentralization, the Empty Summit.

Without those things, you know, sort of notoriously, the internet began because they said, look, in a nuclear exchange, any central command node would be exterminated. So we have to build a system out of military necessity that is intrinsically decentralized enough to survive a nuclear attack. So, you know, it’s exactly programmatically a liberal social and technological project.

So maybe I’m drifting a little bit off your question with that second part. The first part, I would say, yes, there’s deep necessity about the way this is all played out.

Alexander Dugin:

So, I have some remarks, but if we consider how great the technological achievements were in the alternative ideological events. So, for example, some technological breakdown of the Soviet society based on totally different ideological premises.

So, that was totalitarian state, obliging the traditional Russian people that didn’t want to get into this technological trend, that was very balanced society, without this special will to dominate, to develop, to discover something new, but that was obliged by the totalitarian system.

And that has given huge results, for example, the rockets, the space technology that we use now. So, we have, during this communist era, have developed much more than during capitalist three decades of the liberalism. So that was total destruction in our country. Liberalism has brought with itself the total, total devastation of the economy and not a kind of the impulse to create something.

Everything was created during the totalitarian Soviet time. And if we compare that with the achievements or technological achievements of Nazi Germany, So, Soviet Union and West, we will look very, very modest, comparing with this huge and very crazy breakthrough of German racist Nazi technology.

So, we never re-confessed that, but the impact of their huge expansion during 12 years, so they gave much more impulse to the technological development than liberals.

So, that is just a remark. And the second point, I think that paleomodernity, the concept, very interesting, paleomodernity. So, there is two way to interpret the modernity as such. So maybe I’m wrong, but Mr. Land, you have different phase in your philosophy. I’ve tried to study your texts and books. So in the first stage, maybe I’m wrong. So you was a kind of advocate of this new modernity and acceleration of modernity, following new modernity until the last results of the passage from the humanity to this hyper-technological order.

And that was a kind of concentration of the same impulse but led or brought to the logical consequence. That was very, very consequent and very, very complete and metaphysically beautiful, I would say, very nice vision.

And in the last phase, maybe I’m wrong, so you advocate much more this kind of moderation and that, so the liberalism by the modernity, that was the right thing and new globalist development, this internalization, universalization is something exaggerated or some outside kind of hubris in Greek, hubris, so when you come out of the limits, national limits, but there are, in your personal case, we have two forms of interpretation of the modernity and I agree rather with your first phase when there was a kind of description of the modernity as the project of the complete dehumanization of humanity and a way to come to some outsides of the Earth, of the humanity, of the history, to some very ominous, a bit frightening perspective of the future with the total replacement by the humanity and by life on the Earth, by something completely different.

And that was very, very, very beautifully explained, I think. So in your early version of your philosophy, there was the kind of line of modernity pointing to total self-destruction and self-overcoming of the life, of the history, of the time.

And in that sense, the paleomodernity served just as the first stage of the same project. And that, as traditionalists, I agree. So it seems that you were completely right. But there is the other version. And that, I think, is very close to MAGA. So, Make America Great Again movement tries to separate paleoliberalism, paleomodernity, paleocapitalism from the neo-capitalism, neo-modernity, neo-progressive.

So, both positions of yours are very pertinent, I would say.

Nick Land:

But oh, sorry oh yeah sorry I’m just gonna say that in so far as there is that separation it’s because it okay there’s an interference pattern because of the fact that modernity is meaning for us simultaneously these very different things and by paleomodernity I would I’m trying to hold in using exactly the same sentence in paleoliberalism. In the sense, it’s the empty summit, it’s decentralized systems, it’s decentralized social technology.

And from that, acceleration. And in that sense, I think all the things that now are objects of enthusiasm for accelerationists, techno-accelerationists, are the same. I mean, AI is accelerating, blockchain technology is accelerating, the internet, I guess, is accelerating only in the sense that it’s passing over into those things.

And that’s because it’s still is essentially on this model of decentralized systems without authoritative overcoding by some higher instance. And so on that level, I have totally not become a kind of advocate of moderation.

It’s only that there’s a whole bunch of these other things that we mean by modernity, which I think you predominantly mean when you talk about modernity, to do that I don’t think are at all liberal in any sense, other than wearing it as a skin suit, to do with the hypertrophy of the state, the hypertrophy of bureaucracy in its final phases, this woke lunacy that’s the most culturally ruinous process that’s ever happened in our history and you know obviously in so far as that’s what one is meaning by modernity then it’s not only a question of slowing it down but of trying to completely get off that train.

So yeah, sorry to interrupt.

Alexander Dugin:

No, thank you very much. But it seems that you interpret yourself from the present state. So late Nick Land interprets early Nick Land by the position of late Nick Land. Thank you very much for your, so it’s very important. And I think in the first stage and the last stage, always you are very pertinent.

So, we could start with one point, with the other point, we could get back in your thoughts. So, I think that first stage that I have read your book on Fanged Noumena, that was a kind of, I was very, very, very astonished by that, that it was kind of global confirmation of traditionalist Ghanaian, Evolian, Heideggerian vision of how the world ends.

So, the technological development, this liberation from the human presence, from the Dasein precisely, and this passage to the artificial intelligence, totally technological structures, liberation of the core of the earth, in order to put the end to the life on the earth, that was precisely as we traditionalists, we interpret the will or the very being, very essence of the modernity. Modernity, it is antichrist in our eyes, traditionally.

And before you, you was a kind of some very brave, you were considered by us, not you were, so sorry. So, you were considered by us as the most brave, most brilliant, most consequent philosopher of the thinker who is not hesitating, who was not hesitating to give the whole picture what is going on.

So the modernity was kind of interpreted as the kind of the will of the God’s idols of Lovecraft, old ones, a kind of point of special attractor, the strange attractor that is outside. So, outside of the conceptual being of humanistic culture, and this attraction, it is attracting precisely the humanity to this post-human, post-historical pole.

And that description was fantastic, developed by Reza Negarestani, and we could read something very, very, very, very similar in Quentin Meillassoux and Harman. So, that was confirmation of the most radical presumptions or the intuitions of the radical traditionalist.

But now, you rather share some moderate, conservative, multipolar attitude to what is going on. So, that as well, that demands the big respect. So, no problem, that is much closer to our own position, but I could not get out of the difference.

So, there is early Wittgenstein and later, late Wittgenstein, totally opposite. There is Lautréamont of the Chant de Maldoror. The Lautréamont of the Poésies.

So, knowing global philosophy and culture, we should be accustomed, so it is not something new, but there is very important and very interesting change in your opinion that I, with great pleasure and interest, I’m discovering just now in the online conversation.

Auron MacIntyre:

All right, gentlemen. Well, there’s a couple other topics that I think Nick had laid out there. We’ve already covered liberalism, ethnic and social differences, I think universal humanism. You also discussed the possibility of wanting to get into the nature of time or angels. So, both are going to be pretty out there. So, I guess I’ll just kind of let you tee up what aspect of either of those would you like to explore. Mr. Land?

Nick Land:

Actually, if I could interject one, I think it’s kind of maybe a transitional one. Which maybe because we’ve actually not been very at each other’s throats actually I’ve noticed in this thing, so maybe there’s something that would be more contentious, which is to say that one of the things I have the most problems with of your analysis of modernity and where we are and liberalism, is your identification of what you identify as the Cartesian subject. Because I think that this, again, the paleoliberal, the Anglo subject, is almost the opposite of the Cartesian subject.

I mean, it’s like, if I just take the example of AI, the top-down model of artificial intelligence, Marvin Minsky, all these guys, that was in control. That was Cartesian. And the machine learning model is, I mean, I would almost say, is liberal, is decentralized.

You know, it’s, it’s like, the Cartesian model is French, Cartesian social engineering is again, top-down, it’s completely not the empty summit, it’s, you know, so I sort of, I think there’s a, I’m very reluctant to accept that description as being a very accurate pinpointing of the problem with the subject that you have.

It seems to me, I mean, maybe the dominant subject of global liberal hegemony has become more Cartesian. I think that’s extremely possible.

But I think that essentially the liberal trend that has led to where we are is something that has been in competition with a Cartesian model of subjectivity and has, at least in its own mind prevailed over that Cartesian model of subjectivity.

Alexander Dugin:

So, but if we consider Scotland’s tradition of Reid or Ferguson or Hume, for example, that was a kind of rationality, individualistic rationality, but that was the kind of sound reason. So, the reason, common reason, it is not just something totally individual, it should correspond to something general.

So, I think there are just two approaches in my opinion. So there is a universalistic approach of French continental rationalism and that is much more individualistic approach of Scottish British individualism, but they come more or less in my opinion to the same because there should be something common or you could induce it from starting from your own individual position as the concept of common sense of Adam Ferguson and Founding Fathers of the United States, that is pluralistic understanding of something common, something general.

So, you construct something general starting from the different divergent sometimes points or you impose that as a Cartesian subject, strictly speaking in the narrow sense from the top down as in the French tradition. I agree.

But in my opinion, the problem is in Cartesian subject that is closed on the top and when you try to ameliorate the situation, to save the situation, proposing to the multiplicity, to the plurality of the subjects to make their claim on the something common, I think that you could not avoid the same republican logic.

So, in order to solve the problem of the openness, I think we should start from understanding of the human and we need to open the rationality to something other than rationality, not by these deduction or induction. So in both cases, I think, in Cartesian strictly, in strict sense of Cartesian subject or this common sense approach, we are still doomed to some closed territory.

So we need to open the human, we need to find a way how to make the rationality to be led to the pre-rational reality.

Rational element that was called by phenomenologists, by Brentano, active intelligence and active intellect.

So there is something that is not rational, it is pre-rational inside of us and that is openness, that is apophatic dimension and that could not be reduced neither to this unique Cartesian content rationality, need nor to this multiplicity of the subjective individualistic rationalities as in the Scottish version. So in my opinion, this problem can be solved and the opening, by the opening of the human mind into something more than human and than mind.

And that will create the real dimension of freedom. And that will create a kind of totally different access to organizing society. And that will be open summit, but in different interpretation.

So, that is my opinion. And so, Cartesian subject and its strict and narrow acceptance, I agree with you, it matches much more the continental philosophy. But in my opinion, individualistic plurality of the reasons doesn’t solve the problem, that’s my opinion.

Nick Land:

So maybe we should move on to the eschaton. If there’s a way of doing that without a hugely massive leap. No, by all means, go ahead. I mean, I always find myself in these situations wanting to do, get involved in extremely elaborate discussion about time.

And I don’t know whether, what we’re like in terms of time. I mean, but I think a lot of things open up.

I mean, if I again start in the critical mode, which I think I can probably get sort of consensus on quite quickly, it’s that whether we’re looking at the biblical frame, or we’re looking at the critical philosophy frame, we’re led in both cases to a critique of the standard commonsensical model of progressive temporality.

And everything that follows from that in terms of our notions of agency, our notions of historical process, at our notions of the outside and whether the actual deep influences on historical process. So whether it’s Kant saying time is a condition of possibility for objectivity, the most interesting one and complicated one by far.

And therefore, if you’re thinking of it as an object, that is a pre-critical metaphysical error. This is obviously something, again, that’s taken through to Heidegger. Obviously, being in time is called being in time because that’s stripping down the problem of transcendental philosophy to its basic elements.

Or whether in the biblical context, we’re talking about what is summarized as providential history of what is meant as trust the plan, a time organized by the eschaton, so that the notion of common ordinary human agency as something that is basically affecting a causal process from the present on the future and therefore will bring about whatever future is volitional for those subjects, that they’re in a position where basically how the future turns out is been decided now by us, that’s obviously theologically and critically disruptive by these two frames.

And so I guess that’s, a lot of this is very relevant to the discussions that we’re having about history, what is happening in history, it cannot simply be the case that at a certain point in history certain mistakes were made that led to bad things happening. It’s like that is a kind of, there’s an element that is inescapable from that, but that can’t be, that simply can’t be the story because that is a sort of secular history story that is inconsistent with any sophisticated understanding of time.

So that seems to me to be the kind of introduction to maybe a phase of conversation.

Alexander Dugin:

So first of all, I would like to say that I have dedicated to the problem of time 47 lectures and two volumes. It will be published soon and so I thought many years about that as you. So, first of all, I think that according to my exploration of the metaphysics of time, I have come to the conclusion that there are many types of times.

So, there is not only one time. So, we have Christian time, we have biblical time, we have Iranian time, modern time, historical time, Newtonian absolute time, that has nothing to do with the progress. So that is much more entropical.

So Newtonian physical time, it was united by evolutionary theory and Bergson’s idea to, they put them together, they put them together. But originally, Newtonian time has nothing of kind of amelioration of the quality or conditions. That is just continuation of the mechanical laws.

So, in modern science, in modern physics, in classical physics, there is one time, Newtonian time. On the social level, in the modernity, there is totally different time. In the history before them, in the Christian Middle Ages, that was different time. So, we have the plurality of time, of times, and first of all, there is the time with the eternity, that’s Plato and Aristotle, as well as Aristotelian.

Time is the time that is moving around the eternity. There is the eternity center, and there is a kind of movement outside of it, so the rotation outside, and that is totally different time. That is just reflection of eternity, that has nothing special on it.

There is no history, that is just repetition of the same as maybe as an Indian vision. So, there are cultures of civilization without time at all. So, time as well depends on the civilization. So, what we are dealing with, it is a kind of Iranian time, Zoroastrian time, where there is the line, there is the process. And that is explained in the Zoroastrian tradition by the existence of the absolute evil and absolute good.

And only existence of absolute evil makes the history something meaningful. So, without that, it will be just a play. But if there are a real fight, So, who will win, the god of evil or God of good?

So, that makes the history something really that doesn’t matter. And that was accepted by Christianity. Maybe by after Babylonian, post-Babylonian Judaism as well, as preparation for Christianity. So, we have inherited, we Christians, we have inherited this Zoroastrian time, historical time, with open ends, and coming from the top to the bottom.

So that is declining time. So, the time that is going from the paradise to the hell, and in that sense, I have recently we discovered your concept, Mr. Land, about degenerative ratchet. So, there is something in this linear time seen from a demonic, from evil points of view as some degenerative ratchet, something that you could not reverse.

You could not return the tradition because you are obliged to get only one way down. So, that is a kind of attraction of the pole of Antichrist in the history, but the end of this degenerative ratchet, as you have pointed out as well, could not be achieved coming back because there is no way.

It’s linear time, it’s metaphysical time, it’s very important time, but we need not to reverse this line. But we need to say no to this process, to this modernity, to this trajectory, to this orientation.

We could say no and we could make an effort to deny the logic of this unilateral orientation, that is spiritual eschatological revolution. And I think, speaking about Eschaton, we are approaching the point when the result of the negative elements of the history are assembled.

So we are approaching the point of absolute night, the midnight. And Heidegger was very attentive to that. Once he said, we are already in the midnight. Oh no, not yet, not yet. There is the kind of some smallest element, some distance, smallest distance that separates us still.

Not yet, not yet in the midnight. So we are approaching the midnight and the concept of Eschaton is precisely like that because inside of imminent version of it, so the time will never end. Because if you are in total solidarity with the time going down, it will last forever.

It is the eternity of the hell. So you are going down, down, down, and that has no end. And if we say, stop, stop here. So if we have enough, so let’s stop it. So we have achieved the midnight, the point of midnight. It is about not yet. As for the Eschaton, it is about how we consider the situation we are in, so already or not yet.

So it is not objective element of historical time. It is a kind of metaphysical judgment to it. And if we say, so we have enough, so it is midnight, just now, right now is one point.

If we say, oh, not yet, not yet, we didn’t explore the other forms of transgender culture, we need more technological devices, we need more body-positive women. So, we don’t have enough. So, we need to progress further. So, it is not yet, but it is not in the objective structure of time when we achieve or not achieve yet the point of Eschaton.

This is my vision. So, I’ve tried to explain it.

Nick Land:

I mean, obviously the way you’re talking about this confirms the fact that there’s the question of agency and the philosophy of time are completely interconnected in a way that you, if you’re talking serious about one, you move over onto the other.

And so I’m sort of wondering about this thing, when you say we say no, I mean obviously there is a reading of what that means that would be, you know, it would be the most kind of idolatrous mode of humanistic subjectivity and the most unsustainable notion of progressive time where time is moving forward, we’re moving it forward, the way it moves forward is in some fundamental sense our decision, and there’s not historical structure that is organising the decisions in any way that we make.

It seems to me, because I know that you appeal to the language of eschatology, and I’m assuming with that that you are invoking the entire theological framework of time that’s relating time to eternity through eschaton and complicating agency through providence through angels.

So yeah, so what I’m trying to say is, you know, are you not a little bit worried that this sort of decisionistic claim could be misunderstood very much and fall below the level of sort of critical transcendental philosophy or sort of biblical framing that I think you want to invoke.

Alexander Dugin:

So, thank you. When I’m speaking about the decision, decision is decision, So, I don’t rely on the capacity of the human person to get rid totally from influence or to decide the logic of history. There is something that is much more than us.

But I think that the problem of time, it is as well a kind of intervening times existing in our heart. So we could every moment go this way or the other way inside of us, not on the superficial of our existence.

So inside of us, there are two times, the time of angels and the time of the history of this ratchet, of this degenerative ratchet. So being human, in my opinion, we are absolutely free. We are free as God, but we are not omnipotent as God, but we are free exactly at the same level as himself.

So he could, the God who creates everything, we are not, we could not do what we want. We are not omnipotent, but we are free. The freedom is the kind of divine element of us.

So we could be in solidarity of the time And that goes in a different way, in a different direction, so we could get to the river in every moment that brings us to the different ocean, to the different sea. So that is the decision that affects us, but it could affect as well the whole ontology.

And beside or outside this degenerative ratchet that is coming only down, we could choose the way to not to be solidary with that. And there is ontological possibility included in that, in us, because the real nature of time doesn’t coincide with the scientific, a very difficult capitalist, modernist, technological, modern, linear time.

There is the dimension of the eternity embedded in time. It’s very difficult to discover. It is very difficult to find. But it is. It exists. It is hidden. It is not absence. And the vision or the kind of absence of it, it is just the cover.

So, if we discover this entrance inside of our heart, we could find the way, the access to the other time, the authentic time. The time links to the eternity, angelical time. And this time is in a radical contradiction with the time we’re living in.

So that is a kind of revolutionary time, a time of spiritual transfiguration. And that is not mystical, that is not about some individual or subjective experience. That is something, something critical. And I think when Heidegger spoke about the time as the future, because according to Heidegger, interesting, the time is going from the future to the past, not from the past to the future.

He is dealing in Sein und Zeit and his Time and Being with totally different concept. The time coming from the future into the past. As well as Aristotle, the same. Because entelechy, taking the telos, the goal inside, it is precisely that gives the totally different pathological dimension for the history of the being.

So we are attracted by both poles, by the pole of this doom of negative demonic time, It is how I interpret your degenerative ratchet or the end of history of Guénon or kingdom of the quantity of Guénonian.

So that is a kind of pole of attraction or sub-human, sub-infracorporeal attraction. There is one side and we are going precisely there. Welcome to hell, we are already there. And there is the kind of other fluid, other direction inside of time.

And inside of the same time, the very same time. And we discover that, we could grasp it in a moment. So, there is totally different history. We are changing the direction of the history, not on the subjective way, but in general, in an integral way. That is about what is a point of attraction to us in the future and that is Heideggerian concept.

So and according to Heidegger was Ereignis, the event, so if we are attracted by the event we are fighting with in the same camp as the angels for the end of time because that is the fight about the end of time, because there are two opposite interpretations of the end of time.

We are approaching it anyway, but interpretation differs, not the same, the very moment. The moment is common, but interpretations are opposite. So that is the kind of, to be on the side of the angels, not on the side of the demons in the moment of the last judgment. And that depends on our free will, on our freedom.

Nick Land:

I mean, that’s all very interesting. I’m not 100% sure I’m entirely grasping everything that you’re saying. I mean, you definitely… There’s lots of different elements to what you’re saying that I think all maybe would be great to tease apart. I mean, at one level, there’s the question of the multiplicity of times that I take is, in a way, a restatement, actually, of the multiplicity of Daseins.

I mean, for Heidegger, to be extremely crude about it, I mean, Dasein basically is time. And so if you’re pluralizing Daseins, you are pluralizing temporalities, and that’s a very interesting and persuasive move.

Move. I don’t, thinking through exactly where, what the implications of that would be is complicated. And then there’s the question obviously of, which when I was trying to work out notes for this whole discussion, it came up in a lot of different forms, which is that the basic,

I think a metaphysical contradiction, the tension, the paradox of our religious tradition, one extremely germane to this, as we’ve seen just from what you’re saying, but could for sure have seen before that, is about whatever language we choose, like libertarianism in its theological sense, metaphysical freedom, free will, volition, and necessity, Ananke, destiny, fate.

And it seems to me that that problem is, and it’s hard to find exactly the word, I think it’s not even just a paradox because it’s not that it’s not that one side necessarily necessity is right it’s not the other that libertarianism is just right it’s not that it’s simply a paradox either it’s a motor I mean I think the fact we have history the fact we have the history of religion but the but history in general is because the that thought trying to understand the relationship between freedom and necessity is something that is not resolvable now on either pole, and neither can it just be dismissed as something that is irresolvable in principle and has no dynamic force. It’s in a way the driver of religious innovation and the movement of history.

And the kind of very sad thing about secular modernity, I mean probably a lot, is the fact that it has so pitifully failed to maintain the tension of this. It’s basically, it has just resolved to have a complete system of mysterianism and a complete system of metaphysical freedom, and treat it as if there’s no contradiction between them, no problem.

So if you’re talking about physics, you’re a necessitarian. If you’re talking about economics and incentives and all of that, you’re a volitionalist, libertarian. And you have these two completely incompatible frames running simultaneously. And you think that somehow by doing that, by being in a state of constant, extreme contradiction that is not even being explored, you have made some advance upon the Middle Ages.

I mean, it’s an extremely weird thing. And so, you know, when you invoke freedom, extreme freedom that is the freedom of God without the omnipotence of God, I see yourself relating to that to that problem.

And, you know, I guess I would say, you know, I guess I’d say it’s, it’s complicated, because, because, on the other hand, there’s freedom, and there’s also necessity. And it’s like, if you’re, if the claim to freedom is such that it seems to actually be extinguishing the question of necessity.

You know, in theological terms, extinguishing providence, extinguishing the eschaton, extinguishing, depending how the argument is set up, the omniscience of God. Then, you know, that’s not going to be a sustainable.

That’s an over-radicalized or over one-sided commitment that is going to require balancing and balancing within a dynamic paradox, within a mystery, the other side of the equation.

Alexander Dugin:

So interesting. So the problem is, I think, that’s where we have the point of freedom. So that is about where we situate the point of the freedom. So if we think it is in the normal subject, in the human subject, there is no freedom at all, because it is totally controlled, formatted as hard disk, it is just programmed.

So, a normal human is just a program inside an operating system, nothing else. That is, here is some kind of destiny. So, the destiny of updating the operating system. So, that is, and we could follow that trace through the history.

So, but in that sense, in order to define where the freedom is, I have developed, many years ago, the concept of radical subject, maybe you are acquainted. That is something that appears, that manifests, when all the form of subjectivity of human human being is taken out.

It is when the human becomes a total slave. So it’s just the algorithm. So when everything in us, inside of our reason, mind, psychology, bodies, everything is controlled but some outer power of society, of the state, of the cathedral, and so on, by the republic.

And when you have the illusion to be free, it is not yet accomplished. You need to pass through the extreme experience of having nothing at all by yourself, as in totalitarian, an extreme totalitarian system. We have, we were there during Soviet time, you are entering that or maybe you are already something very comparable, because modern-day liberal dictatorship is something very, very close.

So you have no right to think otherwise than you are obliged to do. So that is a kind of expropriation of your inner self. So, you have nothing inside. Everything is dictated by political correctness, by cancel culture. So, you are totally cancelled.

Your subjectivity is totally cancelled and given to you after some process of the cleaning. So, you should be… So, we passed by that. That is why I am speaking so easily about that. We passed by totalitarian experience, Soviet time, and now it is totalitarian experience of liberal time, so you are repeating the same experience.

But what is important? When there is nothing, when there is nothing inside you, only totalitarian state purging everything, cleansing everything inside, you come sooner or later, or maybe you don’t come, but it could be possible to come to some core or something inside of human being that is absolutely independent from that.

So, that is maybe the inner self of Indian tradition, maybe it is the zeitgeist of Heideggerian thought, maybe it is the same of active intelligence and active intellect of Meister Eckhart, Dietrich von Freiberg, but that is something that is more inner side of you.

So the soul has the domains, the circles. And that is the inner circle of all the circles. So everything is expropriated from your soul, there is only the core. This core, it is the origin of the freedom. That is apophatic center of the man, that something is pre-rational.

So that I call radical subject. So, the solution about this point of freedom inside of us, I agree that everything inside of us as well is controlled, is programmed, is manipulated inside of us, except this moment.

And if we discover this element, we know the reason of real freedom. So, it is not about the human, it is something much more radical than human, much more inner than human inside of us, not outside. So, that is important. It is not easy to explain, but if we start to construct this concept of how eternity is possible inside of the time that it destroys everything except itself.

So, we need to think Eschaton in the context and the relation to this critical subject.

Auron MacIntyre:

Well, yeah, we obviously can do this for a very long time. Didn’t discuss duration of the discussion at the beginning so if either of you needs to leave or you know time runs short please just let me know but I would like to ask both of you since recently the latest episode of Tucker Carlson was on artificial intelligence and whether or not it is in its own right Satanic and Mr. Land here figured rather prominently in that discussion, Mr. Dugin was also mentioned. And so I’d be remiss if I didn’t, you know, ask you guys about kind of perhaps how you were portrayed. I’m not sure if you saw the episodes or not. But but I think the larger insinuation, especially on Mr. Land’s part by the guy who was being interviewed was that ultimately your, your pursuit was Luciferian in nature. In fact, basically you’re a Luciferian theophysist, right? Like that, you know, you’re kind of rooting for the serpent in the garden.

And ultimately, I think that you were trying to commune with evil or Satan at some level through explorations of numerology, Kabbalah, these types of things. I’m not sure that’s how you would characterize, but of course, I think you admit at some level that what you were doing with the CCRU was attempting to contact the outside through numerology to gain some understanding of this.

So I guess, how would you answer kind of those basic formulations of your work and what you were doing with the CCRU?

Nick Land:

Well, I mean, the reason that I almost started this with the quote from Faust is I think that frames the question really well. I mean, you know, Samuel Johnson famously said the first Whig was the devil. And I mean, I think, I think Goethe is sort of saying the same thing.

And, you know, I think the Whigs have a case, you know, and I think that it’s like in the. Anglo-Protestant Whig tradition there is always a complicated relationship to what can be crudely, well the crudest, called Satanism.

You know, I mean William Blake famously said about Milton, who I think is the crucial moment here, he was of the devil’s party without knowing it. And that’s because he is exploring questions that are really pretty much exactly what we were just talking about now, and most recently, which is the relationship between liberty and necessity, or understanding the providential function of, I would say rebellion, of the providential function of doing it biblically as Milton said, when the whole constellation of the story of Paradise Lost, the whole constellation to do with the eating from the Tree of Knowledge, everything involved in that, Satan’s role in that, the war in heaven that led to Satan’s strategy in the garden, all of that, is that within an overall providential scheme or not? And I think that like the crude Christian position implicitly is that, oh no, it isn’t.

You know, that somehow, I mean, I’m saying crudely, critically. It’s to say, you know, none of this need have happened. There needed to have been no war in heaven. There needed to have been no eating of the fruit of knowledge. There therefore needed to have been no history. All of that is just a mistake.

But I think the more serious biblical response is to say, you know, what do you mean by a mistake? I mean, this is in a framework that doesn’t, I think, have room for a mistake at that level. It doesn’t, the whole schema cannot be, like, basically skewed by mistake, made at the level of a human agent in time. You know, the notion that, I mean, I’m putting it in more orthodox religious language that I would go to the stake for.

But, you know, the notion that God’s plan for the world can be thrown off course by a woman being persuaded by Satan to eat from the Tree of Knowledge, I think if that isn’t heretical, then it’s like something is really deeply wrong at the core of your religious conception.

It’s such a weak, pathetic and even victimological notion of divinity that it could be disrupted by human agency in history that it’s merely like, to use Tucker Carlson’s word, disqualifying. You know, I cannot, I cannot overstate how disqualifying that would be as far as I’m concerned.

So that’s, that’s basically my position. And I think that these things, I think there’s a question that’s a religious driver. And that, you know, to pretend that that question is resolved at the level it would have to be to lead to a simple denunciation of that set of ends as kind of biblically characterized is just can’t be right.

It’s just way too crude and it’s too anthropomorphic and it’s involving a kind of completely idolatrous notion of divinity, divinity as ultimately a buffoon who can be thrown off course by a human act in history, that just can’t be right.

Auron MacIntyre:

But wouldn’t there, I would say this though, there could, you know, even in your conception here, there would be a difference between, okay, this does have to be part of God’s plan, this does have to be divinely ordained, this is providential, and I’m going to be on its side. I am going to be contacting it, I’m going to be trying to summon it or understand it, explore it, encourage this particular path, right? Those things could exist where this is indeed something set in motion by the divine and part of a providential plan, but it doesn’t mean you have to side with it, I guess, is kind of what I’m trying to say there.

Nick Land:

Well, I mean, I don’t know. It depends what you mean what you’re siding with. I mean, from my point of view, I’m siding with the plan. I’m siding with the story. I’m siding with what-.

Auron MacIntyre:

The original plan to what trust are there, huh?

Auron MacIntyre:

It’s total “trust the plan” behavior. I mean, and frankly, that overspills into the occult somewhere. It’s like, you know, why would you, why would you put yourself in contact with entities that are this sketchy? And would just say, that’s all trust the plan stuff.

You know, like, I mean, I am a, I am a kind of extremely finite, limited entity in history, and I’m honestly not well positioned to start doing cancel culture on the angelic sphere. I mean, it’s just, I think it would be silly to do that.

It’s like, you know, I think if something is taking you deeper into the process, if something’s taking you deeper into what is actually the deepest level, the process that you’re involved in and that you’re here for, that you’re alive for in this reality, if you don’t want to get deeper into that, that seems odd to me.

So, yeah, I mean, you know, and I can understand, okay, that in the crudest terms possible that could be called Satanism, but I really do not think it’s actually Satanism in this. It’s not about having some preference for the defiance of divine purpose on earth. It’s the absolute opposite.

It’s actually an attempt to attune in the deepest way possible to the deepest level of divine purpose. And, you know, I think to describe that as Satanism is not helpful, but there are deeper levels to that because I think that, you know, that too is providence.

That too is providence. It is about why they’re a secret. It’s about why they’re things that are not for everyone. It’s why there are doors with warnings on them. It’s why there is the occult. The occult is part of the plan, obviously. If everyone was supposed to simply be in a state of perfect enlightenment about what is happening in history, they would be.

So the fact that people are, in their own ways, groping in the dark, and in whatever way possible, trying to attune themselves to what they think is right, that is part of the process.

So, you know, I’m not saying it doesn’t make any sense that people say this, or, you know, it’s wrong for people to say, I mean, I think it’s just like that in the big picture, of course, there has to be. Professor Dugin, would you like to respond?

Alexander Dugin:

Oh, interesting. So, you know that there were two poetry schools in Britain in 19th century, Byron and Lake School of Words. And when people from Lake School, they have accused Byron to be Satanist, to be at the side of the evil.

So Byron have responded to Wordsworth, that if you would be in my place, if you would experience something more or less close to what I have experienced, said Byron, I will speak with you about Satan and God. But because you contemplate these things at the same distance, I have nothing to say with you.

So, there are people of depth, there are people of the inner core of the reality who experience some things that could not be evaluated and claimed and called in a simplistic way. So, that is my opinion. So, I think that the accusations during this interview with Tucker Carlson were very funny, ridiculous. So, that is…

And I was wondering who is this guy who appeared there in Carlson. He said many times, I have shown in my show, I’ve tried to find some traces in the Internet about this personality and I have found nothing. So maybe it is artificial intelligence creation as Mr. Land has suggested before our meeting.

So we should not respond to Grok, so Grok should respond to us, not ourselves. So that is the group person, so combining some elements of everything and putting them on the same scale, it’s ridiculous. But the serious problem, what is a serious problem, that is Antichrist. So, I think that is Eschaton, it is serious. Satan is serious. So, the logic of history, the modernity, radical enlightenment, dark enlightenment, the ontology of artificial intelligence is serious.