Hiroshima and the Containment of Political Eurasia

The rise of the nuclear order and the eternal clash between Sea and Land

Pierre-Antoine Plaquevent unveils the birth of the nuclear order and the cosmopolitan creed that transformed war into a planetary duel between sea power and Eurasia.

In 1945, the alliance between the political West and the Soviet Union triumphed over the fascist Axis. Yet this alliance of convenience between a denazified political West and Stalinism was ideologically and strategically unnatural; it could not endure. The Western powers anticipated this and fully understood that once their common, immediate enemy had been destroyed, they would soon find themselves face-to-face with Stalin and the Soviet Union.

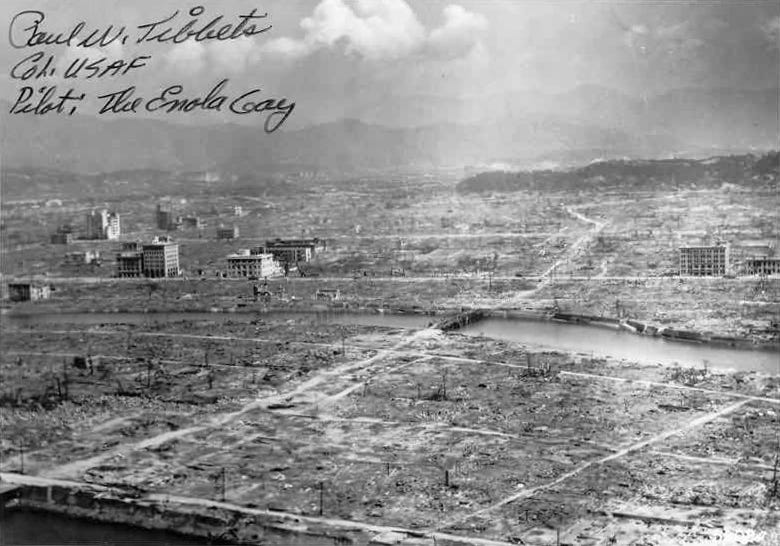

For many historians, the decision to use atomic weapons against a Japan already on the brink of military defeat was, in fact, meant as a strong signal to the Soviets — to deter their advance towards the Pacific. This interpretation was advanced by the Jewish-American progressive historian Gar Alperovitz. As early as 1965, he argued that the use of atomic bombs on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki was, above all, intended to strengthen the United States’ position in postwar diplomatic negotiations with the Soviet Union.1 The use of the atomic bomb was thus driven by political considerations even more than by military ones:

The most obvious alternative explanation was put forward by early postwar critics who pointed out that there is considerable evidence that diplomatic reasons concerning the Soviet Union — not military reasons concerning Japan — may have been important. For instance, after a group of nuclear scientists met with Truman’s chief adviser on the atomic bomb, U.S. Secretary of State James Byrnes, one reported that, ‘Mr. Byrnes did not argue that it was necessary to use the bomb against the cities of Japan in order to win the war [...] Mr. Byrnes’ [...] view [was] that our possessing and demonstrating the bomb would make Russia more manageable.’2

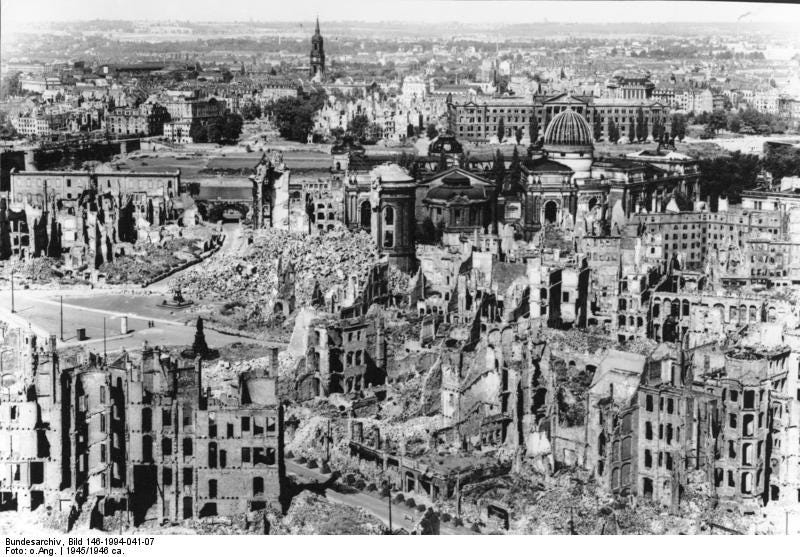

The devastating bombings of Dresden a few months earlier, in February 1945, had served a similar purpose: to crush Germany into unconditional surrender and to “impress the Soviets.”3 Across the western and eastern edges of Eurasia, the geopolitical demarcations of the coming Cold War were already taking shape.

The atomic bombing of Japan marked the beginning of the containment policy towards the USSR that would prevail throughout the Cold War. It was the first act of a geopolitical orientation against Russia and political Eurasia that continues to this day. After their defeat and occupation, the Axis powers were transformed into strategic outposts, allowing the thalassocracy to maintain control over the Eurasian Rimland and contain the expansion of Heartland powers towards the “global ocean.”4

The goal was to impose nuclear hegemony swiftly and to stun the world into submission. Yet establishing that strategic supremacy came at an unprecedented human cost. Even as the Axis was already defeated, 1945 saw an unmatched ferocity directed by the Allies against civilian populations.

From February 13 to 15, 1945, the bombings of Dresden wiped its historic center off the map, killing between 25,000 and 50,000 people according to the lowest estimates,5 and between 100,000 and 150,000 according to the highest.6 One month later, on the night of March 9-10, 1945, the bombing of Tokyo marked a decisive escalation in the air war against cities. The firebombing of Tokyo’s traditional wooden districts created a sea of flames that killed around 100,000 people.

The nuclear bombing of Hiroshima on August 6, 1945, killed 140,000 out of 350,000 inhabitants. The bombing of Nagasaki on August 9 took 74,000 lives out of 240,000.

For comparison, the German Blitz killed 43,000 British civilians during eight months of bombing between September 1940 and May 1941 — nearly half of all British civilian deaths in the entire war.7

General Curtis LeMay commanded the massive campaign of incendiary bombings that preceded the atomic strikes on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945. When later questioned about the “morality” of bombing Japanese cities, he remarked:

Killing Japanese didn’t bother me very much at that time… I suppose if I had lost the war, I would have been tried as a war criminal… Every soldier thinks something of the moral aspects of what he is doing. But all war is immoral and if you let that bother you, you’re not a good soldier.8

This mass slaughter reflected the “spirit” of modern total war — conflicts mobilizing entire populations, erasing the distinction between civilians and combatants, and, in our own era, between “wartime” and “peacetime.”

From the First World War to the present, humanity has endured the bloodiest era in its history. At the same time, it has been the period during which cosmopolitanism gradually became the dominant political paradigm in the West — a paradigm that fractures before each world war, only to reassert itself afterward. The twentieth century, an age of unprecedented economic and technological acceleration and globalization, was also an age of unparalleled slaughter.

In Open Society against Eurasia, I estimate that the wars from 1918 to the present have caused roughly over ninety million deaths, without even counting the massive political upheavals of the Bolshevik and Maoist revolutions, among others.

Here lies one of history’s great paradoxes: the more the belief in cosmopolitan idealism has become a consensus among Western elites, the more war and violence have spread throughout the modern world. Western man now lives in a virtual bubble, detached from the reality as it is experienced outside the globalist West. That bubble is beginning to burst.

Political globalists claim that “nationalism means war,” whereas cosmopolitanism is said to be intrinsically peaceful — only because the latter promotes pacifist slogans to mobilize consciousness in favor of its own interests. As history has shown for a century, globalist pacifism is not synonymous with peace but with the criminalization of cosmopolitanism’s strategic enemies and an escalation towards extremes against the enemies of the Open Society.

According to a realist geopolitical paradigm, one might even state the following axiom: if nationalism means limited war within and through an inter-state framework (and therefore a political one), cosmopolitanism means war beyond limits, through the erosion of states and of classical inter-state warfare. And war without political limits tends towards world war. Cosmopolitanism, in its very essence, tends towards world war — in the name of a final struggle against war itself and against the enemies of the Open Society.

The culmination of this boundless world war was the use of nuclear fire by the cosmopolitan West against the civilian population of a nation already defeated on the battlefield, as we have noted. The only restraint on escalation towards total nuclear war — pushed to the very limits of matter through atomic fission — was, paradoxically, the sharing of nuclear power among strategic states. From this sharing arose a geopolitical equilibrium that checked cosmopolitan hegemony and established a division whose trajectory pointed towards multipolarity. Where nuclear monopoly drives cosmopolitan unipolarity, nuclear balance gives rise to geopolitical multipolarity.

For this reason, several leading advocates of the pre-1945 nuclear race — Einstein among them — later became proponents of UN-style nuclear non-proliferation. Officially, this stance was justified by pacifism and the fear of universal annihilation; in practice, it served to preserve the strategic hegemony of the Western-globalist bloc within the world-system.

The Americans held an exclusive monopoly on nuclear weapons from 1945 to 1949. Despite Soviet advances in nuclear science, the United States retained nuclear hegemony until the 1960s. In 1955, the U.S. possessed about 2,400 nuclear warheads, while the USSR had only 200; by 1960, the U.S. had 18,600 and the USSR 1,600. Yet by the 1980s, Russia had caught up — and even surpassed — the United States.

It is always along the Rimland that the bloodiest conflicts occur and that the greatest pressure is exerted between the Anglo-American thalassocracy and the powers of the Heartland.

(Translated from the original French article here)

Gar Alperovitz, Atomic Diplomacy: Hiroshima and Potsdam, 1965.

Gar Alperovitz, “Atomic Bombs and the Early Cold War,” 06/08/2016.

Frederick Taylor, Dresden: Tuesday, February 13, 1945, 2005.

For discussion of these concepts, see: Pierre-Antoine Plaquevent, Open Society against Eurasia, Strategika, 2023.

Frederick Taylor, Dresden: Tuesday, February 13, 1945, 2005.

David Irving, The Destruction of Dresden, 1963.

To complete the analysis, one has to consider that Japan was merely firebombed (terrible and devastating but nearly as fear educing as a single mythical N. bomb would be). Otherwise, it's like trying to geo-politics without understanding the 911 eleven inside job, or the stand down by Israel October 7th. Both Nukes & COVID-19 have been fear based propaganda and physiological warfare. Without using these truths, even insight full evaluations will come to the wrong conclusions.