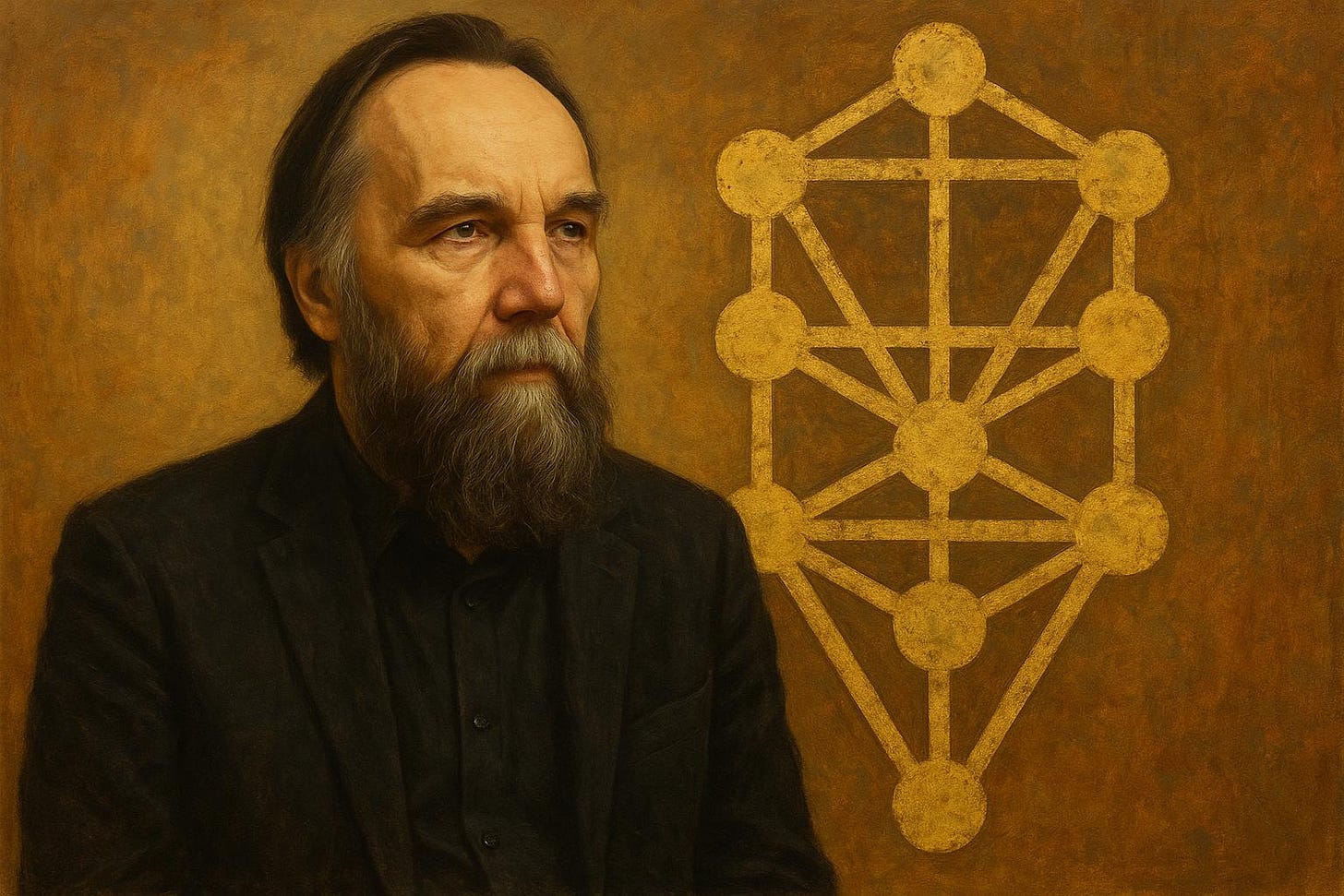

Dugin and Kabbalah

The sacred roots liberalism chose to forget

Constantin von Hoffmeister examines how a misquoted debate shows Alexander Dugin invoking Kabbalah to confront liberal modernity’s rejection of the sacred.

Few contemporary thinkers have been so persistently misrepresented as Alexander Dugin. His detractors rarely engage with his actual words. Instead, they rely on fragments torn from longer exchanges, presented in isolation to produce the illusion of irrationality or fanaticism. One recent example concerns his supposed “praise of Kabbalah.” In reality, this line comes from a 2017 debate between Dugin and the liberal American Jewish intellectual Leon Wieseltier, and when viewed in full, the meaning is entirely different.

Here is the video:

The discussion took place before an audience of Western academics, including several liberal Jewish thinkers, among them future U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken. Dugin’s task in this setting was formidable: to defend the idea of Tradition, metaphysical order, and the spiritual dignity of peoples before an audience deeply invested in Enlightenment universalism.

Wieseltier begins by declaring the obsolescence of all traditional wisdom:

There’s nothing whatsoever new about populism, and there is nothing whatsoever new about the mystical faith and the wisdom of the people. These are very old ideas and, in my view, very old mistakes, because one of the things that history shows…

In this opening, Wieseltier dismisses both populism and mystical tradition as outdated errors, relics of a pre-rational age. His argument implies that all appeals to “the wisdom of the people” or to sacred inheritance must ultimately lead to tyranny or delusion. It is the standard liberal thesis: that freedom is safeguarded by skepticism, by procedural reason, and by the deliberate neutralization of the collective soul.

Dugin interrupts him with a provocative statement, one that strikes at the roots of his opponent’s own civilization:

The Kabbalah tradition is the greatest achievement of human spirit.

The line, so often cited against him, was not a sermon but a challenge. Dugin invoked the Kabbalistic tradition—so deeply embedded in Jewish metaphysics—as an example of a living spiritual inheritance. In doing so, he was forcing Wieseltier to confront a paradox: how can one deny the value of Tradition while belonging to a people whose mystical system has inspired centuries of intellectual and religious life?

Wieseltier responds by doubling down, speaking with the calm authority of a liberal rationalist:

My friend, I have studied the Kabbalah my whole life in the Hebrew language, and I have to tell you that it has absolutely nothing to do with the wisdom of the people. What history shows is that the wisdom of the people frequently becomes justifications for terrible crimes. And that what passes as the wisdom of the people can lead directly to evil. And the American system, certainly, when the Founders wrote our Constitution, they considered populism. They called it direct democracy. And they ruled it out in favor of representative democracy, precisely so as to make possible deliberation and rational consideration of the issues facing the country.

This response is revealing. Wieseltier explicitly rejects any association between Kabbalistic wisdom and the collective spirit of a people. He warns that what is called “the wisdom of the people” can become “justifications for terrible crimes.” To him, the democratic Founders were right to suppress direct participation in favor of a mediated, technocratic order: an order of reason over soul, deliberation over passion, and universalism over identity.

Dugin’s brief intervention, when restored to its context, acquires its full philosophical weight. He was not “promoting Kabbalah” to Orthodox Russians or praising Jewish mysticism. He was confronting his opponent with the latter’s own sacred heritage, using it as a lens to reveal what modern liberalism has lost. Dugin’s remark, “The Kabbalah tradition is the greatest achievement of human spirit,” is an ironic yet serious appeal to the reality of transcendence—an appeal to the idea that humanity once aspired to comprehend the divine structure of being, and that such aspiration is higher than the managerial pragmatism of modernity.

Yet, in isolation, that single line has been weaponized to paint Dugin as a crypto-mystic preaching esoteric doctrines to the masses. The full video refutes this. It shows a rigorous philosopher using rhetoric strategically, pressing his adversary to acknowledge that even within the Jewish tradition, there once existed a hierarchy of meaning and a conception of cosmic order entirely alien to liberal egalitarianism.

This was the essence of Dugin’s confrontation with Western thought: the defense of Tradition against the reduction of all values to procedural neutrality. In the same discussion, he speaks of Trump, of the return of history, of the need for civilizational plurality, and one can sense the unease of the audience. The liberal intellectuals, accustomed to speaking from the moral summit of “progress,” suddenly encounter a man who rejects their framework altogether.

The 2017 debate remains one of the most illustrative encounters between two visions of the world: one that venerates the sacred, and another that worships reason’s self-sufficiency. When Dugin speaks of Kabbalah, he is not abandoning Orthodoxy or Russia. Instead, he is reminding his listeners and critics that even their own faith traditions once reached upward towards the Absolute. That gesture—philosophical, rhetorical, and civilizational—remains entirely faithful to his broader project: to resurrect a world in which spirit, not abstraction, defines the destiny of peoples.

Populism, in its deepest sense, transcends the conventional divide of left and right. It is the pulse of the collective will: the cry of a people yearning for meaning against corporate sterility. Whether clothed in socialist or nationalist colors, populism affirms that politics is not mere administration but destiny, the reawakening of spirit in history.

Kabbalah is an ancient Jewish way of seeing the world as a living chain between God and man. Fragments fall, letters rearrange, and light cracks open the code. Kabbalah teaches that all creation flows through ten stages of divine energy, linking the heavens and the earth. Scribblings in the margins, circuits of breath, the divine current rewired. Each part of life reflects this pattern, from the movement of stars to the thoughts of a person. A name folds into another, sparks fall through the alphabet. To study Kabbalah is to search for how the spirit moves through the world and through oneself, giving order, meaning, and direction to existence. Everything connects, disperses, and returns, rewritten in light.

I think “We” must thank Alexander Dugin for defending the Hebrew Kabbalah against the demagogues of Jewish modernity 😭; the kind of self-enlightened minds like Leon Wieseltier, who embody everything that went wrong after Mendelssohn/Friedländer&co.

When the reformers of the german Haskalah reduced the Kabbalah to a mere superstition, the so-called “Jewish rationalism” was born, and with it, the slow death of Jewish metaphysics (Sorry for saying this). For this rationalism, all mystery and transcendence was translated into sociology, and the infinite made ethical. The liberal Jew confuses the Kabbalah with magic, superstition, or folklore, “Populism”; he doesn’t know that what he calls “irrational” is, in truth, supra-rational; the very structure of divine life.Liberal jews speak of “reason,” of “progress,” of “ethics,” but what they really defend is a Judaism amputated from its own vertical fire… Wieseltier is a perfect example of that liberal rationalism: what could he possibly know about Kabbalah? Only inherited prejudices.

The Jewish Enlightenment at its romantic afterglow, by “universalizing” Kabbalah, destroyed it. It desacralized what it could not penetrate and, later, blamed the sacred for the chaos it had caused. From there was born the thick demonization of Kabbalah that infected both the Left and the Right: the rationalist who mocks it as myth, and the conspiracist who sees in it a dark code of satanic control. They are twins; the same modern disease, the same blindness turned in opposite directions. There is no mystical tradition so vilified, so misunderstood, so methodically inverted as Kabbalah. And yet, the Jewish Kabbalah is the hidden grammar of Western mysticism and Christian Kabbalah. One cannot understand Christianity, nor the deep architecture of European thought, without passing through the Kabbalistic imagination.

Scholem saw this clearly when he said that the Kabbalah is the true soul and original thinking of Judaism. The Kabbalah cannot be studied as a discipline (and yet it can be); something Christianity lost a long ago and Islam, contradicting here Rene Guénon, never really had, only perfically; namely, esoterically. The Kabbalah annihilates the liberal mind: it destroys the fantasy of human autonomy as its true nature by restoring vertical dependency, the great chain of being where knowledge is received, not just invented under X or Y criteria. There is nothing absurd in an Orthodox Christian studying Kabbalah, why?... The theosis of the East and the devekut of the Kabbalist are mirrors: both point to a transfiguration of being through participation in divine light. I have spoken with true Orthodoxs, those not corrupted by politics or modern ideologies (idolatries), and with them the dialogue on mysticism reaches heights that few Catholics could approach and almost no Protestants at all. In those conversations, the language of Ein Sof and the language of divine energies converge. The tzaddik and the staretz speak the same metaphysics. Orthodoxy, through Byzantium, drank deeply from that same fountain. The apophatic mystics of the East, who speak of the uncreated light, move within the same metaphysical geometry as the Kabbalist ascending through the Sefirot toward Ein Sof. Both negate in order to affirm, both rise by silence, both unveil the Absolute through unknowing. The Orthodox and the Kabbalist are two forms of the same vertical being. The politics of the church and the way the jewish people fighted the humiliation doctrins is a completely different topic. So yes; I thank Dr. Dugin as a rare defender of the sacred axis. Mysticism is not the margin of religion, but its center; the world stands not by reason’s calculation, but by the descent of divine light.

Aleksandr Dugin’s invocation of the Kabbalah as “the greatest achievement of the human spirit” raises an interesting question about the source and nature of wisdom within a tradition. The Kabbalah, as a mystical interpretation of the Torah, represents an esoteric pursuit—a quest for hidden meanings and divine mysteries accessible only through disciplined study and spiritual ascent. It is not populist in the sense of being immediately available to the masses; rather, it presupposes hierarchy, initiation, and depth -- all of which support Traditionalist thought.

Christian tradition, particularly in its patristic and ascetic streams, shares this layered approach. While the Gospel is proclaimed openly to all, the deeper mysteries—the Logos, theosis, and the contemplative life—require spiritual formation and grace. Both traditions affirm that wisdom does not arise from mere instinct or “faith in the people,” but from participation in something transcendent: for Kabbalah, the emanations of the divine; for Christianity, union with Christ, the Logos made flesh.

Thus, if populism is framed as mystical faith in the collective, Wieseltier is correct to see a tension. Neither Kabbalah nor historic Christianity locates ultimate wisdom in the crowd but in the divine order that calls individuals upward. The real question is whether modern populism can be reconciled with any authentic tradition—or whether it is, as both traditions might argue, a symptom of the loss of transcendence.

The important contribution of modern populism to the political landscape is its rejection of the left-right paradigm. This certainly fueled the populism in the United States. In Putin's case, it may have been reactionary to the unipolar paradigm after the fall of the Soviet Union.