Why Is Stalin So Popular in Modern Russia?

Putin, power, and the return of Stalin

Nicholas Reed on how Putin revived Stalin as a symbol of order, power, and national revival.

At the turn of the millennium, Russia teetered on a precarious geopolitical edge. A nation scarred by the wild 1990s, grappling with whether to cling to the chaotic promises of neo-liberal reform or reclaim echoes of its ironclad Soviet resolve. The economy was a rotting corpse, being feasted upon by oligarchs, whose loyalty to Moscow’s interests was dubious. Russia had just endured a decade of hyperinflation, privatization scandals, financial collapse in 1998, and the borders of the USSR fractured into 15 squabbling republics with their own regional wars. Enter Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin, an enigmatic former KGB officer who reveres Yuri Andropov and Peter the Great as equals. The Yeltsin-era oligarchs dismissively call Putin a ‘grey blur’, unremarkable, unthreatening, yet he was relentlessly ascending.

Putin’s climb was a masterclass of political maneuvering: Deputy Mayor in St. Petersburg, where he navigated corruption and reform under Anatoly Sobchak, then director of the FSB in 1998, restoring discipline to the security services, briefly Prime Minister in 1999, and finally acting president on New Year’s Eve 1999, when a weary Boris Yeltsin abruptly resigned. Putin’s swift election in March 2000 was sealed by a decisive military campaign in the Second Chechen War, which projected strength and order amid the chaos. Russians woke up, and for the first time in over a decade, they had faith in the future.

One of his earliest and most symbolic acts as president struck at the heart of Russia’s fractured identity: the restoration of the Soviet-era state anthem, composed by Alexander Alexandrov in 1944 and long associated with Joseph Stalin’s era. The tune, majestic, stirring, unmistakably martial, had been discarded in 1990 by Yeltsin, who replaced it with Mikhail Glinka’s wordless ‘Patriotic Song,’ a 19th-century instrumental piece meant to evoke pre-revolutionary Russia without communist baggage. But Glinka’s melody never resonated, failing to inspire a nation adrift. In December 2000, Putin pushed through legislation to revive Alexandrov’s music, but with fresh lyrics by Sergei Mikhalkov, the very poet who penned the original Soviet words in 1943 and revised them in 1977.

The new verses spoke of a ‘sacred’ Russia, vast and enduring, ‘protected by God,’ blending patriotic fervor with subtle nods to tradition while purging references to Lenin, communism, or the ‘unbreakable union.’ The move ignited fierce debate. Communists cheered the return of a familiar rallying cry; many ordinary Russians, polls showed, favored it for its emotional power. Yet liberals and Yeltsin loyalists decried it as a step backward, evoking ‘Stalinist repressions’ even if the words were sanitized. The ailing former president Boris Yeltsin, in his first public criticism of his handpicked successor, reacted with quiet dismay. When a reporter asked if he had known of Putin’s plans, Yeltsin shook his head. Pressed for his thoughts on the revived anthem, he offered a single, loaded word: ‘Krasnenko’—reddish, a sly evocation of the Bolshevik ‘Reds’ and a subtle jab at the creeping revival of Soviet shades. In this one act, Putin signaled his vision: not a full return to the past, but a selective reclamation, fusing imperial symbols (like the retained tricolor flag and double-headed eagle) with Soviet strength to heal a divided nation.

It was a masterstroke of symbolism, setting the tone for an era where order, pride, and continuity would trump the raw uncertainties of the Yeltsin years. Russia, under its new helmsman, was charting a course neither fully West nor East, but unmistakably its own.

Yet it must be emphasized: the yearning for restored Soviet prestige and stability was not a mere top-down imposition, but a profound grassroots aspiration among ordinary Russians. As the red banner was solemnly lowered over the Kremlin on December 25, 1991, replaced by the tricolor of a new Russia, the dissolution of the USSR felt like a profound national trauma to many. Just nine months earlier, in the landmark March 17, 1991 referendum, an overwhelming majority had voiced their desire to preserve the union. With an 80% turnout across the nine participating republics, 76.4% of voters (over 113 million people) affirmed the preservation of the USSR as a ‘renewed federation of equal sovereign republics,’ one guaranteeing human rights for all nationalities.

This was no coerced outcome; it reflected a genuine public sentiment that the Soviet Union should evolve and modernize, not evaporate. Russians, along with millions across the multinational state, did not crave a return to ‘Stalinist repression’ or rigid central planning in its harshest form. They yearned for reform: abundant consumer goods on store shelves (ending the chronic shortages of the late Brezhnev era), peaceful détente with the West after decades of Cold War tension, and technological leaps to rival global powers.

Perestroika and glasnost under Mikhail Gorbachev had kindled hope for exactly that, a revitalized socialism with a human face. At first, it appeared the Gorbachev-Yeltsin tandem might deliver. Yet disillusionment set in almost immediately. The Belovezhka Accords, signed in secret by the leaders of Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus in December 1991, unilaterally declared the USSR dissolved, overriding the referendum’s clear mandate without further public consultation. For millions, this felt like an elite betrayal. The ensuing ‘shock therapy’ under Yeltsin, rapid privatization, price liberalization, and market opening, unleashed hyperinflation (peaking at over 2,500% in 1992), factory closures, unpaid wages, and a plunge in living standards. Pensioners scavenged for food, once-proud industrial workers faced unemployment, and oligarchs amassed fortunes through rigged auctions of state assets. This chaos fueled enduring nostalgia.

Independent polls by the Levada Center, tracking sentiments since the early 1990s, consistently show a majority regretting the USSR’s collapse, peaking at 75% in 2000, dipping to a low of 49% in 2012 amid economic recovery, but climbing again to around 63-66% in recent years. Respondents cite the loss of a unified economy, social guarantees (free healthcare, education, jobs), and superpower status.

In the wake of economic devastation and national humiliation, Russians turned decisively to the ballot box, overwhelmingly backing candidates who promised to reverse the chaotic course of radical neo-liberal reforms and restore a sense of order, dignity, and social protection. Such as in the December 1993 parliamentary elections, held just months after Yeltsin’s violent standoff with the old Supreme Soviet, a crisis that saw tanks shelling the White House in Moscow. Voters delivered a stunning rebuke to the pro-reform forces: Vladimir Zhirinovsky’s ultranationalist Liberal Democratic Party of Russia (LDPR), a bombastic outfit blending populist rage with imperial nostalgia, shocked the world by capturing 22.9% of the proportional vote, emerging as the largest single-party bloc with 64 seats.

Zhirinovsky, the fiery showman who had already placed third in the 1991 presidential race with nearly 8% of the vote, railed against corruption, crime, and the loss of superpower status, vowing to protect ‘ordinary Russians’ and reclaim lost territories.

Close behind were the resurgent communists, with Gennady Zyuganov’s Communist Party of the Russian Federation (CPRF) securing about 12% and 48 seats. Pro-Yeltsin blocs, such as Russia’s Choice, limped in with just 15.5%. Two years later, in the December 1995 Duma elections, the tide turned even more decisively leftward. The CPRF, now a disciplined opposition force channeling widespread nostalgia for Soviet-era stability, triumphed with 22.3% of the proportional vote and a total of 157 seats, nearly 35% of the chamber, making it the dominant faction in a parliament increasingly hostile to Yeltsin’s agenda.

Zyuganov, who blended Marxist rhetoric with Russian patriotism and admiration for China’s gradualist reforms, positioned the CPRF as the voice of the dispossessed: pensioners hit by hyperinflation, workers facing unpaid wages, and citizens yearning for guaranteed jobs, healthcare, and national pride. He criticized ‘shock therapy’ as reckless, reportedly questioning how Russia could compress into mere years what had taken advanced capitalist nations like the United States a century to achieve. Zyuganov advocated a ‘measured’ path, state control over strategic industries, social welfare restoration, and inspiration from Deng Xiaoping’s China rather than blind Western imitation. He also dangled the dream of Eurasian reintegration: not a forced Soviet revival, but a voluntary union of equal republics, echoing the unfulfilled promises of Gorbachev’s New Union Treaty while appealing to those mourning the USSR’s abrupt dissolution.

By early 1996, with the CPRF commanding parliament and polls showing Zyuganov as the frontrunner, the presidential election loomed as a potential turning point. In the first round on June 16, Zyuganov took 32%, narrowly trailing Yeltsin’s 35%. The runoff on July 3 became a fierce referendum on the 1990s: Yeltsin, bolstered by oligarch-funded media blitzes framing the choice as ‘reforms or red revenge,’ eked out victory with 53.8% to Zyuganov’s 40.3%. Allegations of irregularities, media bias, and vote manipulation in regions like Tatarstan, as well as oligarch influence, swirled, but Zyuganov ultimately accepted the results.

These electoral surges were unmistakable evidence of the Russian people’s profound desperation: a cry for stability amid plunging living standards, for the restoration of state benefits eroded by privatization, for reclaimed superpower prestige in a world where Russia felt diminished, and for renewed faith in a collective future rather than the atomized uncertainties of wild capitalism. The groundswell from below, not elite machination, created the political space for a figure promising disciplined renewal, one who would soon emerge to harness this longing without fully reverting to the communist past.

To communists, nationalists, and ordinary citizens alike, the towering figure of Joseph Stalin resonated deeply in the turbulent post-Soviet years, a symbol not of unalloyed terror, but of unyielding strength in an era when Russia felt weak and adrift. Stalin’s own grandson, Yevgeny Yakovlevich Dzhugashvili (1936–2016), a retired Soviet Air Force colonel and fierce defender of his grandfather’s legacy, emerged as a vivid embodiment of this reverence. Living between Russia and his ancestral Georgia, Yevgeny became politically active in the 1990s, positioning himself as a vocal Stalinist. In the 1999 State Duma elections, he featured prominently as one of the leading faces, often listed third on the federal ticket, of the radical ‘Stalin Bloc – For the USSR,’ a coalition of hardline communist groups including Viktor Anpilov’s Labor Russia and the Union of Officers.

Despite the electoral disappointment, Yevgeny’s visibility underscored a broader trend: Stalin’s image, officially denounced by Nikita Khrushchev in 1956 and further marginalized under Gorbachev and Yeltsin, was undergoing a profound grassroots rehabilitation. Independent polls by the Levada Center, tracking public opinion since the late Soviet era, reveal Stalin consistently topping lists of Russia’s ‘most outstanding’ historical figures.

The Russians were famished for that same ironclad resolve. They wanted their country to be pushed into the future, for a bright and vibrant future to be in the present, no longer a fairy tale promised by faltering and sickly authorities. Stalin’s enduring appeal, carried in banners through Red Square and etched in public memory, laid bare a society’s profound yearning: not for tyranny’s return, but for the certainty of greatness restored.

Vladimir Putin’s presidency swiftly delivered on the Russian public’s deepest cravings for order, strength, and reclaimed dignity, outpacing Gennady Zyuganov’s resurgent Communist Party in electoral landslides that underscored a national pivot toward disciplined renewal over nostalgic revival. In his first term, Putin secured reelection in March 2004 with a commanding 71.3% of the vote, dwarfing the Communist candidate Nikolai Kharitonov’s meager 13.7% (Zyuganov sat out the race, endorsing a proxy). Eight years later, returning for a third term in March 2012, Putin captured 63.6%, again relegating Zyuganov to a distant second with just 17.2%. These margins reflected not rejection of communist ideas per se, but endorsement of Putin’s pragmatic fusion of state authority and market stability, delivering what Zyuganov promised without the ideological and historical baggage.

Central to this appeal was Putin’s decisive taming of the Second Chechen War, which had been launched in 1999 amid separatist incursions and apartment bombings by Chechen militants. Even more resonant was Putin’s confrontation with the Yeltsin-era oligarchs, widely reviled as ‘social parasites’ who had plundered national wealth through rigged privatizations, showing no loyalty to the motherland while millions sank into poverty. In the 1990s, figures like Boris Berezovsky pulled strings behind Yeltsin’s throne, turning the president into what critics called a marionette. Putin flipped the script dramatically. Shortly after his inauguration, in the summer of 2000, he convened Russia’s most powerful tycoons for a pivotal gathering. Accounts from participants like banker Sergei Pugachev place it symbolically at Joseph Stalin’s preserved Kuntsevo dacha (also known as Blizhnyaya Dacha) on Moscow’s outskirts, a site evoking the Soviet leader’s purges and absolute power. There, amid the unchanged relics of Stalin’s office and couch, Putin reportedly laid down the law: keep your amassed fortunes, ‘but stay out of politics and out of my way’. The message was unmistakable: state authority trumped private empires.

A parallel meeting on July 28, 2000, brought 21 oligarchs to the Kremlin, where Putin pledged no reversal of privatizations in exchange for their political neutrality. Most complied, transforming from kingmakers into a school of frightened fish. Defiers faced ruin: Berezovsky, the media and oil magnate who helped engineer Putin’s rise, fled to exile in London by 2001 amid embezzlement probes. The starkest example was Mikhail Khodorkovsky, Russia’s richest man and head of oil giant Yukos. Convicted of fraud and tax evasion in trials, he spent a decade in prison. Yukos was dismantled, its prime assets absorbed by state-controlled Rosneft, reasserting government dominance over strategic energy sectors. These moves struck a chord with a public long seething at oligarchic excess. Polls consistently showed overwhelming approval for reining in the tycoons. Putin also prioritized rebuilding the Russian military, ravaged by underfunding and defeat in the First Chechen War. Increased budgets, professionalization efforts, and reforms aimed at modernizing forces restored another pillar of national prestige, signaling Russia’s return as a formidable power.

In harnessing grassroots demands for justice, security, and strength, without fully dismantling markets, Putin forged a new compact: loyalty to the state in exchange for stability and pride. It was precisely the resolve Russians had hungered for, propelling his own enduring popularity with Russians.

Meanwhile, the reverence for Joseph Stalin has not faded but evolved into bolder, more public expressions, weaving his legacy deeper into the fabric of contemporary Russian identity. No longer confined to Communist Party rallies or academic debates, Stalin’s image has appeared in unexpected sanctuaries: Orthodox churches and cathedrals, where frescoes and icons depict him alongside saints. Notable examples include controversial paintings showing the blind saint Matrona of Moscow blessing Stalin during World War II, a legend the Russian Orthodox Church deems unverified, or mosaics in military cathedrals placing him beneath the Virgin Mary with Soviet marshals. These depictions, often donor-funded and sparking outrage from church hierarchies and liberals alike, blend sacred iconography with wartime heroism, framing Stalin as a divinely inspired leader who saved Russia from existential threat.

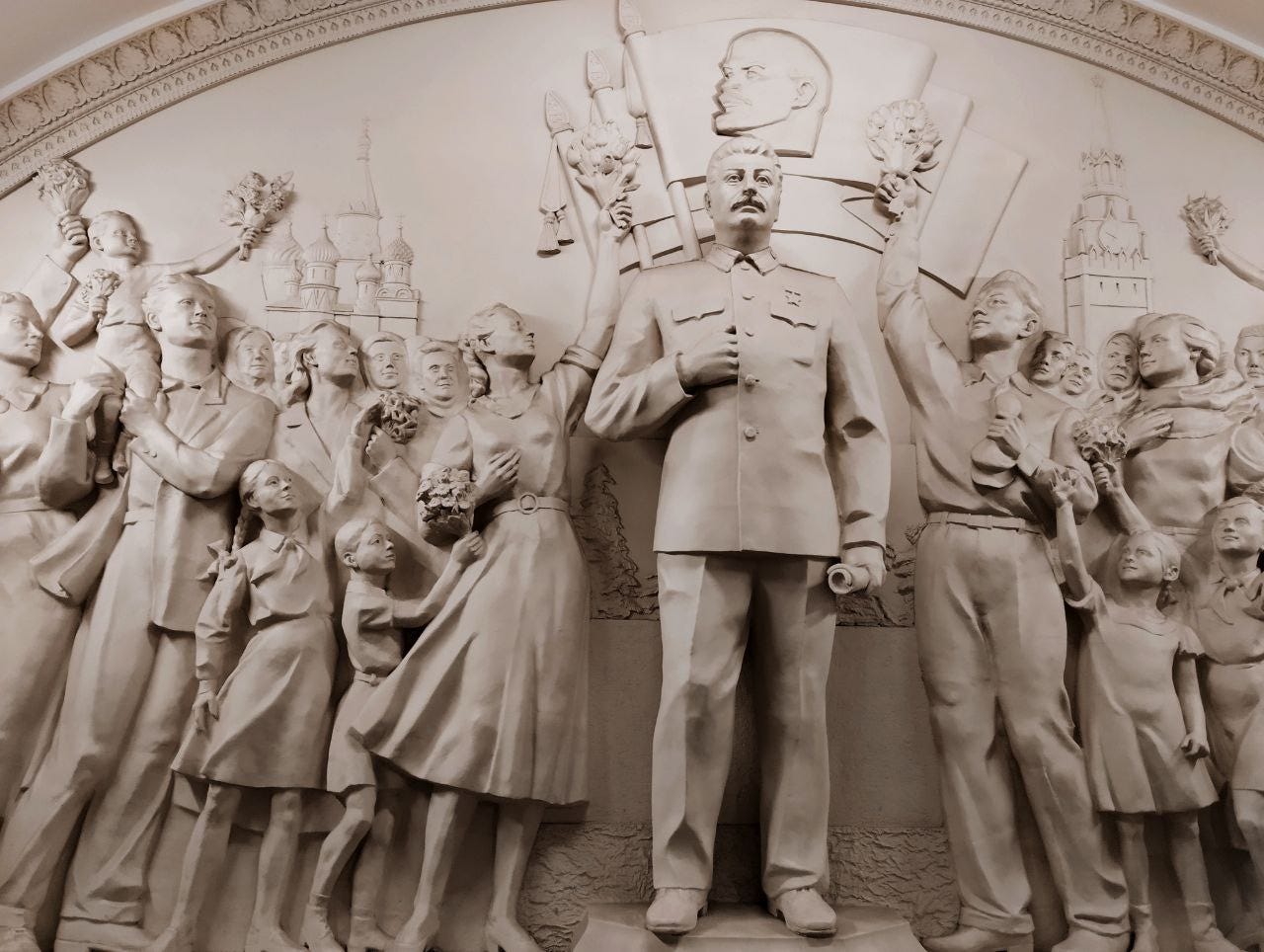

Russians view him as the quintessential embodiment of national greatness, outpolling Peter I (the modernizer) and Pushkin (the cultural icon) in surveys spanning the 2010s and 2020s, with approval of his role reaching record highs around 70%. This revival carries the quiet but unmistakable endorsement of the Kremlin, which sees selective ‘Stalinism’ as a pragmatic tool for statecraft: mobilizing patriotism, justifying strong centralized rule, and equating past victories with present challenges. Since Putin’s ascent in 2000, over 100 new monuments to Stalin—busts, statues, and plaques—have been erected across Russia, from regional towns to Moscow’s metro stations, with the pace accelerating after 2014 and again post-2022.

The annual May 9 Victory Day parades on Red Square have grown ever more spectacular under Putin, evolving from modest 1990s events into massive spectacles of military might, featuring thousands of troops, advanced weaponry, and overt Soviet symbolism: red banners, hammers and sickles, and occasional Stalin portraits carried by participants. These ceremonies, blending imperial eagles with communist stars, reinforce a narrative of unbroken triumph.

To the average Russian, equating Stalin with Peter the Great feels natural. Both are archetypes of resolute leadership that forged greatness from adversity, delivering prestige and security. This synthesis underpins the Kremlin’s broader historical reconciliation: portraying the Soviet era not as an aberration, but as one illustrious chapter in a continuous millennium-spanning saga of Russian statehood, tracing back to the legendary Varangian prince Rurik, who in 862 founded the Rurikid dynasty at Ladoga (or Novgorod), laying the foundations of Old Rus’—the cradle of East Slavic civilization. In this seamless tapestry, tsars, commissars, and modern leaders alike are threads in an eternal story of resilience and sovereignty.

The image of Joseph Stalin has once again been optimized for the modern era of Russia. With the launch of Russia’s Special Military Operation (SMO) in Ukraine, Stalin evokes national defense against existential outside threats. Official narratives characterize the SMO as ‘finishing the fight our grandfathers started’, a direct continuation of the Soviet Union’s 1941–1945 battle against the Nazi invasion. This rhetoric portrays the conflict not merely as denazification, eradicating Banderite neo-Nazism rooted in Stepan Bandera’s collaborationist legacy, but as a broader defense of Russia’s survival against a hostile West. Just as Operation Barbarossa in 1941 aimed at the USSR’s annihilation, today’s confrontation is depicted as encirclement by NATO powers salivating at Russia’s potential downfall, with Ukraine as a proxy battlefield.

This linkage amplifies Stalin’s wartime role as supreme commander, overshadowing his repressions while reinforcing themes of sacrifice and unity against fascism. Central to this worldview is the enduring concept of Russians, Ukrainians, and Belarusians as fraternal East Slavic peoples, branches of a historic ‘triune’ nation (Great Russians, Little Russians, and White Russians) whose bonds trace to Rurik’s old Russian state of 862 Rus. The 1991 Soviet dissolution is mourned as an artificial severance of this organic whole, with Ukraine’s post-Maidan drift toward the West seen as a tragic mistake. Reintegration restores what was lost.

As Winston Churchill warned in his June 18, 1940, House of Commons speech amid Britain’s darkest hour: ‘If we open a quarrel between the past and the present, we shall find that we have lost the future.’ In Russia’s telling, embracing the past, its victories, its strong leaders, and its undivided Slavic kinship secures the future against division and defeat.

By 2020, independent Levada Center polling revealed that 75% of Russians regarded the Soviet era as the ‘greatest time’ in their country’s history, a sentiment deepest among older generations who endured the 1990s’ chaos, yet pervasive across society as a rebuke to that decade’s hardships rather than a plea for communism’s full return. The erection of new Stalin monuments has accelerated since 2022, with dozens added amid the conflict—busts in regional towns, reliefs in Moscow’s metro—signaling a bolder public embrace of his legacy as victor and unifier. In 2025 alone, 15 Stalin monuments were built across Russia, not including smaller busts or facades, which are also plentiful.

As 2026 dawns, Russia’s selective reclamation of its Soviet past persists, with Stalin’s shadow lengthening not as a call to revive socialism, but as a tool for historical reconciliation, satiating opposition through nostalgic symbols of prestige and unyielding resolve. Depicted as a ‘strong helmsman’ guiding the nation through storms, devoid of Marxist-Leninist or collectivist rhetoric, his image bolsters Kremlin statecraft amid the Special Military Operation’s trials. Levada’s 2025 poll crowns him history’s most outstanding figure for 42% of Russians, while over 120 monuments now stand, including seven unveiled in May 2025 alone, like the Moscow Metro restoration at Taganskaya.

In Churchill’s words, avoiding quarrels with the past secures Russia’s future: eternal, undivided, and most certainly, great.

President Putin was correct by saying, "Whoever does not miss the Soviet Union has no heart. Whoever wants it back has no brain."

Thanks for your great work Nicholas!

We've restacked and shared this link on 'The Stacks'

https://askeptic.substack.com/p/the-stacks