The Monroe Doctrine Was Never Meant to Be This

The corruption of a once-anti-colonial doctrine

The Otter examines how a doctrine born in anti-colonial idealism hardened into a creed of dominance.

On December 2, 1823, President James Monroe delivered his seventh annual message to Congress. Amid a lengthy address covering domestic achievements and foreign affairs, he embedded a bold assertion: that the American continents, “by the free and independent condition which they have assumed and maintain, are henceforth not to be considered as subjects for future colonization by any European powers,” and that any attempt to extend European political systems to this hemisphere would be viewed as “dangerous to our peace and safety.”

The proclamation provoked little immediate debate in Congress, whose attention remained fixed on pressing internal concerns. Across the Atlantic, Europe’s great powers largely dismissed it with scoffing disdain, viewing the young republic as an upstart lacking the military might and authority to dictate hemispheric affairs. Monroe and his advisors knew this well; the United States possessed neither a credible army nor navy to enforce such a sweeping claim.

In reality, the statement rested on the quiet assurance that British naval dominance would deter other European powers from intervention. This shrewd calculation was the work of Monroe’s Secretary of State, the seasoned diplomat John Quincy Adams, who had drafted the key passages. Adams firmly opposed a joint declaration with Britain, arguing that it would be more candid and dignified to proclaim American principles unilaterally than to appear as a “cock-boat in the wake of the British man-of-war.” By going it alone, the fledgling nation seized its first real opportunity to assert itself on the world stage.

Adams’s instincts proved sound. In the decades that followed, the principle acquired its enduring name, the “Monroe Doctrine”. Over the years it evolved into a cornerstone of American assertiveness and leadership in the Western Hemisphere.

Latin American leaders, fully aware that the United States lacked the power to intervene militarily on their behalf, nonetheless welcomed the gesture. It bolstered their precarious independence at a critical moment. Simón Bolívar, still campaigning against Spanish forces, received it warmly; Colombia’s Francisco de Paula Santander hailed it as an act of profound humanity and friendship; and leaders in Argentina and Mexico expressed sincere gratitude. Thanks in no small part to Adams’s diplomatic acumen, the young republic had begun to speak with its own voice in international affairs.

The mastermind behind the Monroe Doctrine, John Quincy Adams, was a man of unyielding principle. When he assumed the presidency in 1825, following his service under Monroe, he placed his hand upon a volume of laws, rather than the traditional Bible, as he took the oath of office, a gesture that underscored his reverence for the Constitution and the rule of law.

This act captured the essence of the man. He consistently placed conviction above partisan loyalty: breaking with his father’s Federalist Party over support for the Louisiana Purchase and Jefferson’s Embargo Act; aligning with the Democratic-Republicans only to part ways as the party fractured; and, later in life, becoming a prominent voice in the Anti-Masonic Party, decrying corruption and the hidden influence of secret societies in American politics.

That same character informed his diplomacy. In his celebrated 1821 address as Secretary of State, he declared: “America, with the same voice which spoke herself into existence as a nation, proclaimed to mankind the inextinguishable rights of human nature, and the only lawful foundations of government.”

And he lived by the maxim he often repeated: “Always vote for principle, though you may vote alone, and you may cherish the sweetest reflection that your vote is never lost.”

The Monroe Doctrine, born of Adams’s pen, thus reflects not merely strategic calculation but the nobility of a young republic finding its moral voice on the world stage. The original doctrine rejected “might makes right” arguments, instead raising a moral barrier against the recolonization of weaker states. One might draw a parallel to France’s aid to the American Revolution; though partly motivated by rivalry with Britain, it was also animated by Enlightenment ideals of liberty and republicanism—ideals shaped, in no small measure, by Montesquieu’s writings on separated powers and moderated government, which profoundly influenced both the American Founding and French revolutionary thought.

This ethical foundation of America as well-wisher to liberty abroad stands in stark contrast to later invocations of the doctrine, often justified through the colder lens of realpolitik. In its origins, the Monroe Doctrine embodied the idealism of a nation still learning to reconcile power with principle.

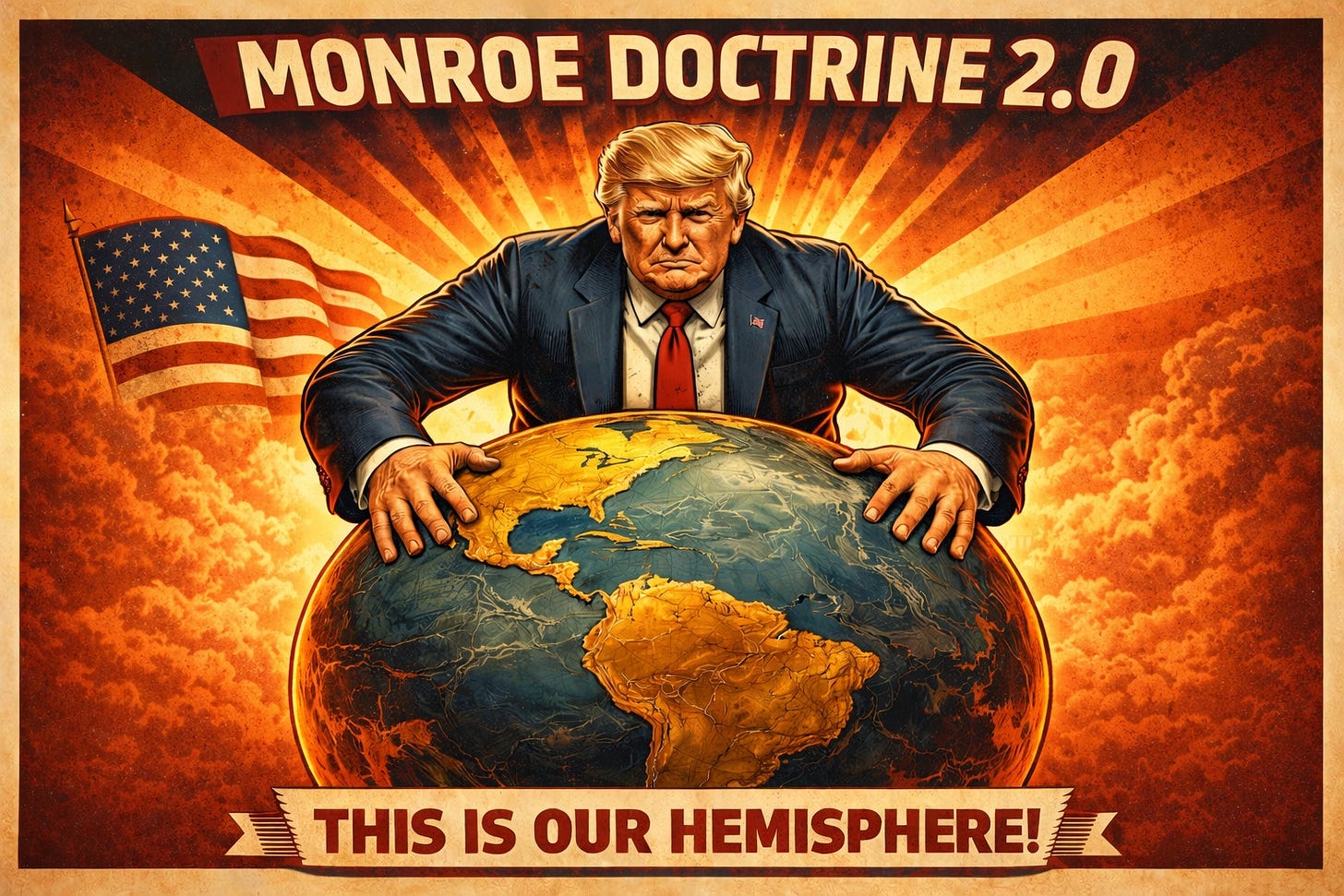

Fast forward to 2025, and the Monroe Doctrine resurfaces in a corrupted form: The Monroe Doctrine 2.0, or what the administration terms its “Trump Corollary” — but is in all actuality a totally different beast. What began as a principled stand for the sovereignty of newly independent New World states has devolved into a blunt instrument of unchallenged supremacy. Far from inspiring enduring alliances, this iteration breeds suspicion and resentment across the international community.

The new doctrine proclaims, in the words of a State Department declaration, “This is OUR Hemisphere, and President Trump will not allow our security to be threatened.” Trump himself, following the U.S. military’s audacious capture of Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro in Caracas, asserted: “American dominance in the Western Hemisphere will never be questioned again.” Its objective marks a stark departure from the original’s moral restraint: no longer content with warding off European colonization, it now seeks to aggressively reassert U.S. primacy by expelling extra-hemispheric influences—chiefly China, Russia, and Iran—through military intervention, economic coercion, and demands for exclusive allegiance. In Venezuela’s case, this translates to severing Caracas’s deep ties with Beijing, halting oil exports to China, and redirecting 30 to 50 million barrels annually to the United States under an “America First” mandate, all to safeguard American interests against great-power rivals.

The old adage holds that one attracts more flies with honey than with vinegar. Then there is Theodore Roosevelt’s corollary to the Monroe Doctrine: “Speak softly and carry a big stick.” Trump, however, has upended both, dousing allies and adversaries alike in acerbic vinegar while bellowing threats of overwhelming force. His “big stick” now resembles a barbed-wire cudgel scavenged from a Philadelphia scrapyard, wielded with all the raw bravado of Kensington Avenue thug.

To be sure, fear can serve diplomacy in moments of stark geopolitical necessity. But consider Trump’s aims here. Venezuela poses a thorn for the United States precisely because of its entrenched bonds with China—a rival Trump has eyed warily since his first White House term. If this “Monroe Doctrine 2.0” is meant to cripple Beijing’s expanding footprint in the Americas, Trump must brace for retaliation: economic reprisals, perhaps a bold seizure of Taiwan, or even the spark of open conflict.

The harsh truth? Trump arrives a decade or two too late to uproot China’s influence. Beijing is woven inextricably into the region’s economies, its investments and partnerships too entrenched to be dislodged without profound upheaval.

In the contemporary arena of Latin America and the Caribbean, China’s ambitions manifest in a calculated hierarchy of interests, beginning with the pursuit of economic dominance through expansive trade ties, which now surpass $500 billion annually in bilateral exchanges underpinned by free trade pacts and investments that embed Beijing deeply into local economies. Closely following is the Belt and Road Initiative’s infrastructure thrust, financing and constructing ports, highways, railways, and digital networks across more than twenty nations, exemplified by Peru’s Chancay megaport and Huawei’s 5G rollouts, to secure logistical footholds and foster dependency. Energy and resource extraction rank next, with billions poured into oil, natural gas, lithium from the Lithium Triangle, and renewable projects like solar farms in Argentina and wind installations in Chile, ensuring supply chains for China’s industrial and green transitions.

The United States aims to disrupt China’s oil supply through its actions in Venezuela, in an effort to undermine Xi Jinping’s Global Initiatives, yet China has already significantly diversified its oil exporters. While the Trump administration’s strategy exerts pressure on China, in the realm of geopolitical realism, it appears more as a bullying tactic than a viable means of curtailing Beijing through these measures. Xi himself has denounced the actions as bullying, stating, “The world today is undergoing changes and turbulence not seen in a century, with unilateral and bullying actions severely undermining the international order.” Furthermore, Trump’s attempts to pressure Denmark into selling Greenland—including with threats of military force—are alienating allies in the so-called “free world,” nations that America should champion as partners under a modern Monroe Doctrine, much as John Quincy Adams once did for his fellow post-colonial states.

America has long dimmed as the radiant beacon it once aspired to be in the chaotic 19th century—a principled repudiation of gunboat diplomacy in favor of Enlightenment ideals and mutually beneficial commerce. No longer does it unequivocally embody the “free world,” that once-cherished bastion of liberty. To be fair, this erosion is not solely Trump’s doing; it is a corrosion that has deepened over decades, as the United States grappled with its post-World War II hegemony. Thrust into the role of global arbiter, it faltered, forsaking foundational principles for the allure of expedient gains and predatory pacts, rather than nurturing alliances rooted in reciprocal respect and shared prosperity.

Perhaps this young empire, saddled with a self-imposed mantle of idealism, was always vulnerable to the gravitational pull of human ambition—a Nietzschean will to power cloaked in the rhetoric of progress. We now stand at the threshold of a post-liberal era, stripped of the anti-colonial ethos that once animated the Monroe Doctrine’s promise to the Americas. Ahead lies a landscape of resurgent rivalries, where the horizon darkens with the specter of unchecked dominance.

Empires of old coalesced gradually, through the alchemy of culture and conquest; those of tomorrow may erupt in a frenzied race toward supremacy. America, China, and Russia are already delineating their spheres, carving out influence from the global map and compelling smaller nations to fortify their sovereignty or yield their sovereignty. Thus, the grand liberal vision implodes, unmasking the emperor in his naked delusion: an “international community” that bargained away its conflicts through naive diplomacy, now revealed as a fragile farce. We revert to the primal frictions of tribal allegiance, which we arrogantly dismissed as relics of a benighted past.

This veneer was always paper-thin; America, the self-proclaimed evangelist of freedom and democracy, has routinely betrayed its own creeds—sidestepping international accords while wielding realist geopolitics like a hidden blade. It was always a mirage, sustained by hypocrisy, but now the illusion shatters for all to see. Might a wiser, more mature nation have preserved these ideals? Or is this the inexorable fate of human nature, drawing us toward self-devouring ruin in the maelstrom of our own hubris?

Its not about oil about transnational corruption trying to destroy us for last 100 years why arent sheeple concerned about the replacements let in and all on welfare the woke the color rev dumb white sheeple impeding the arrest of criminals aka illegals. This is total disruption