The King and the Soul

Plato’s chariot of the soul as the metaphysical blueprint of empire and sacred politics

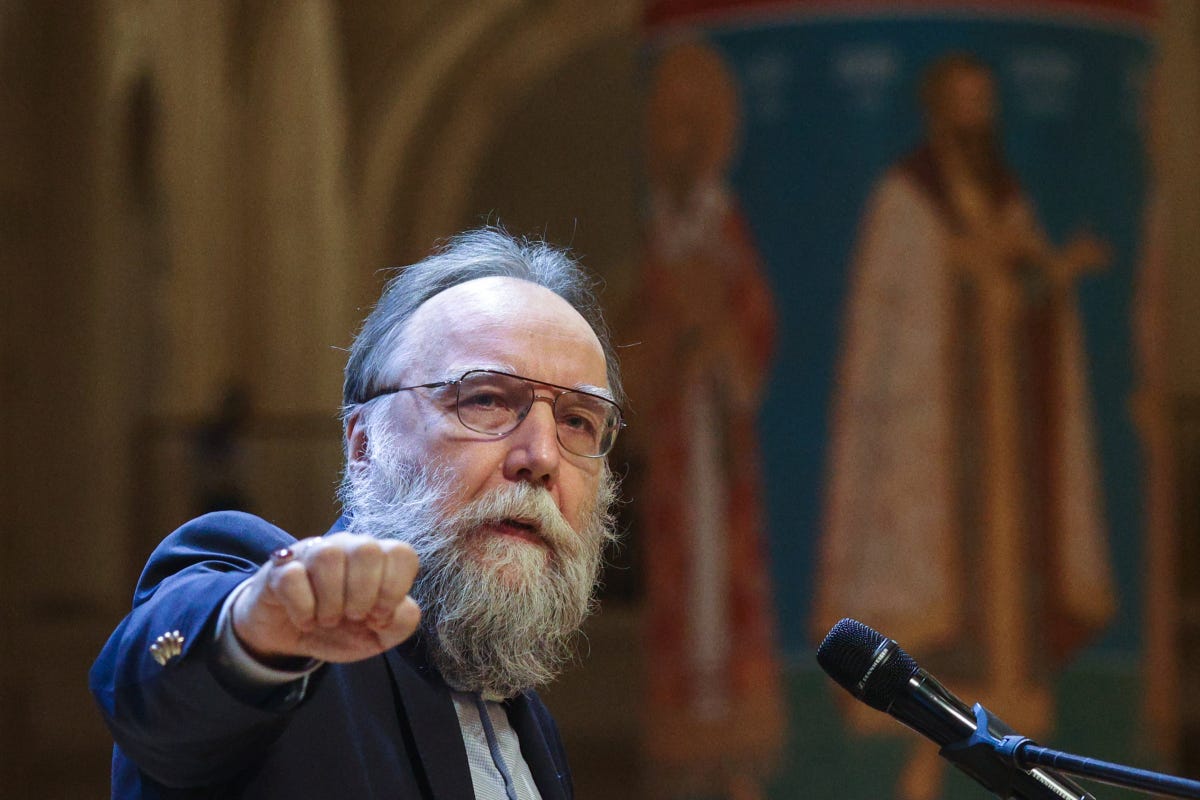

Alexander Dugin explains Plato’s image of the soul and its political meaning.

Plato proceeds from the fundamental principle of a direct homology between the cosmos, the state, and the structure of the soul.

In the dialogue Phaedrus, he describes this threefold structure of the soul through the following images:

Let us liken the soul to the combined power of a winged pair of horses and a charioteer. In the case of the gods, both horses and charioteers are all noble and born of the noble, whereas in others they are of mixed descent.

First, our ruler drives the team, and then among the horses one is beautiful, noble, and born of such stock, while the other is its opposite, with ancestors of another kind. Inevitably, the task of governing us is hard and troublesome.

Here it is important that Plato compares the structure of the human soul with the structure of the souls of the gods: they differ from one another only in the quality and nobility of their parts.

Plato continues his description:

At the beginning of this account, we divided each soul into three kinds: two parts we likened in form to horses, and the third to a charioteer. Let this division remain in force now as well.

Of the horses, we say, one is good and the other bad. We did not yet explain in what the goodness of the one or the badness of the other consists, and that must now be said.

One of them, then, stands in the finer posture: straight and well-proportioned in form, high-necked, with a slightly aquiline nose, white in color, black-eyed, a lover of honor combined with moderation and reverence; a companion of true opinion, needing no whip, guided by command and word alone. The other is crooked, heavy, clumsily put together, thick-necked and short-necked, snub-nosed, black in color, light-eyed, full-blooded, a companion of insolence and boastfulness; shaggy around the ears, deaf, and barely yielding to whip and goad.

As Plato emphasizes, the two horses are unequal: one is better, the other worse; one is white (yet with a black eye—μελανόμματος), the other black (with a light eye—γλαυκόμματος). Thus, a hierarchy is established within the soul:

the charioteer (ἡνίοχος);

the white horse (the good);

the black horse (the non-good, the bad).

In the fourth book of the dialogue Republic, Plato develops this theme further, defining the three components of the soul in the following terms:

the charioteer represents the intellect (νοῦς, λόγος);

the white horse embodies the spirited principle (θυμός);

the black horse represents desire (ἐπιθυμία).

Plato directly correlates these with the three classes of his state:

the highest part of the soul corresponds to the philosopher-kings (the guardians);

the spirited principle corresponds to the warriors (the auxiliaries of the guardians);

desire is the dominant force among the laborers and farmers (the basic population).

In Phaedrus, Plato describes the cause of the soul’s fall into the body as a consequence of the rebellion of the black horse. While the white horse obeys the voice of the charioteer, the black horse does not, and continually strives in a direction opposed to the intellect. The soul falls into the body and loses its wings precisely because of an intrinsic centrifugal impulse within itself, embodied in the black horse, in the property of desire. There is no strict boundary between desire and the body; the body itself is desire turned to stone.

But from another perspective, the black horse is related to the white one: both are horses, although of different origin, as Plato emphasizes. Both qualities—thymos (θυμός) and epithymia (ἐπιθυμία)—derive from a single foundation, from the word thymos, which for the Greeks also served as a synonym for the soul. The Indo-European root of this word, dʰuh₂mós, originally meant “smoke,” a meaning associated with fire and air. Desire, therefore, is first and foremost spirit; yet if spiritedness (thymos), the highest martial virtue, is desire in its pure form, then desire (epithymia) is desire that has become burdened, hardened, and condensed. Pure spiritedness leads towards destruction (towards corporeality); hence the vocation of warriors is to bear death. Burdened spiritedness, or desire, leads towards creation; hence the vocation of peasants and laborers is the creation of products and things, as well as the begetting of children.

The philosopher-king is the one in whom the charioteer is fully capable of subordinating both horses and directing the course of the chariot vertically upward. It is along this very direction that the state is constructed—along the axis between Heaven and Earth and towards Heaven. Empire is a ladder leading into Heaven.

Politics, according to Plato, is a structure of anthropological ascent, corresponding to the elevation of the soul and the purification of its properties. It is precisely this immediate connection between being and politics that renders the state, in the Platonic understanding, sacred.

(Translated from the Russian)

In Plato's rendering then the state is the highest spiritual expression of the human soul? But how does he define "state" ?

Thanks for your great work!

We've restacked and shared this link on 'The Stacks'

https://askeptic.substack.com/p/the-stacks