The Irish Right Haunted by Connolly and Larkin

How Irish conservatism echoes the socialist tradition

Callum McMichael examines how modern Irish conservatism has quietly inherited and inverted the moral and economic ideals of James Connolly and Jim Larkin, transforming their revolutionary socialism into a nationalist creed of labour, virtue, and belonging.

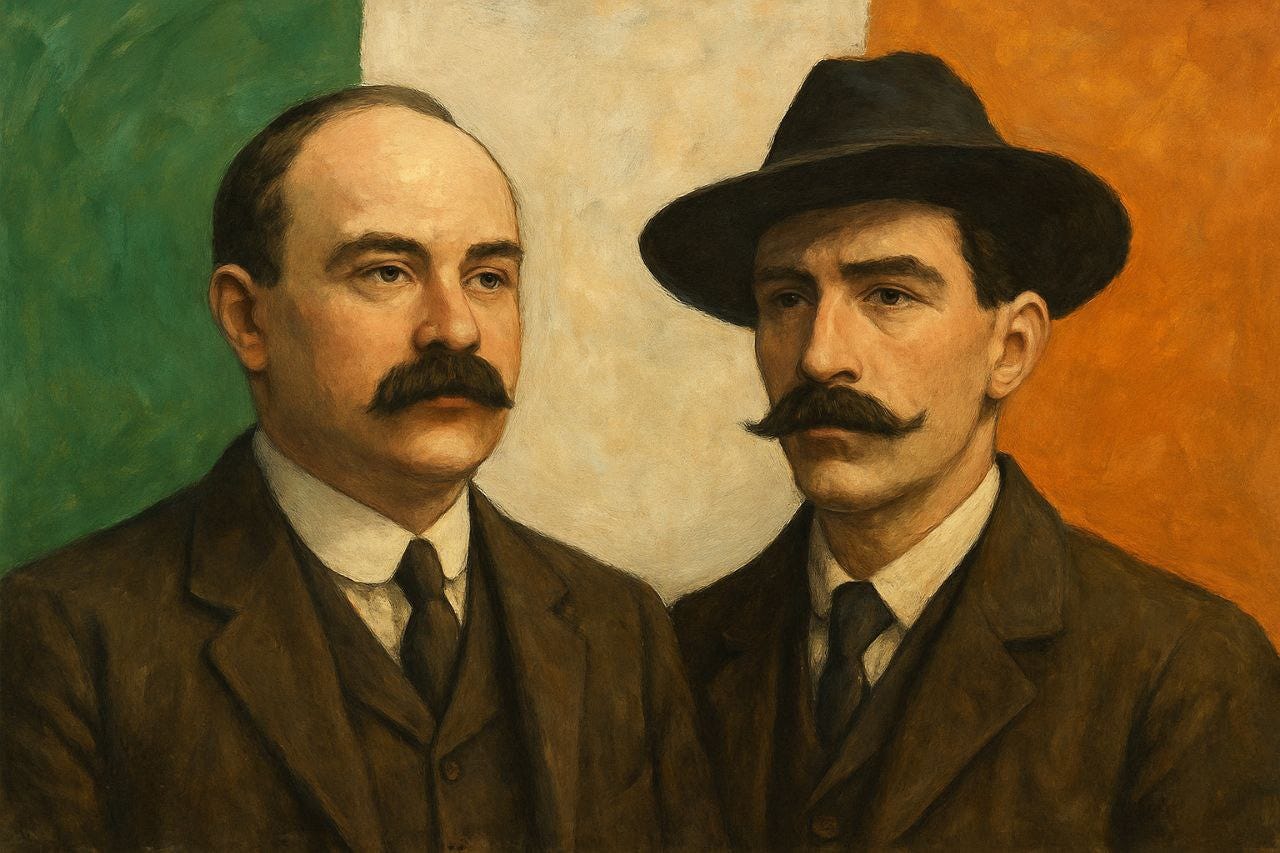

Every nation that outlives its revolutions must learn to perform a delicate necromancy: it must honour its dead rebels while neutralising their danger. In Ireland, this rite of containment has taken on the air of civic piety. The images of James Connolly and Jim Larkin gaze out from murals and postage stamps alike, embalmed in a reverence that masks its own betrayal. They have become, in the collective imagination, not agitators but ancestors—the moral decoration of a state they would have sought to abolish. Yet their ghosts are not quiet. They linger as uneasy presences in a political order that has found ingenious ways to inherit their language while repudiating their meaning.

The phenomenon is not merely historical; it is metaphysical. Every revolutionary discourse, once victorious or defeated, passes through a dialectical inversion: its vocabulary survives, but its referent is altered. What was once a grammar of emancipation becomes a rhetoric of endurance; what once named the intolerable becomes the expression of pride in endurance itself. The Irish right has executed this transformation with particular subtlety. It has absorbed Connolly’s socialism as patriotism and transfigured Larkin’s militancy into moral industriousness. Thus the two most articulate enemies of bourgeois respectability are now enlisted in its defence.

Connolly himself foresaw this danger. In the prophetic passage of Labour in Irish History (1910), where he warns that the raising of the green flag over Dublin Castle would be meaningless without the socialist republic, he is not simply making a tactical argument. He is diagnosing an ontological risk: that the form of liberation may persist while its substance decays. Freedom, detached from the economic structures that sustain it, becomes a simulacrum—a signifier divorced from its material signified. It is this void that later conservatism fills with moral and national sentiment, converting social contradiction into spiritual vocation. The right’s inheritance of Connolly is therefore not an act of plagiarism but of metaphysical substitution.

Larkin, the more incandescent spirit, spoke in a register of righteousness that carried its own ambivalence. His speeches were liturgical in cadence, infused with an eschatological belief in the worker’s redemption. He appealed not to historical necessity but to divine justice, to the “spark of God in every man.” In so doing, he sacralised the proletarian condition even as he sought to abolish it. The moral elevation of labour that made his words irresistible to the oppressed also rendered them susceptible to later re-interpretation by those who wished to preserve labour as a moral discipline rather than as a field of emancipation. The sermon, having outlived the strike, could easily be repurposed for catechism.

Both men thus bequeathed to Irish political consciousness a language of moral seriousness—an idiom in which work, nation, and virtue intertwined. In their hands it was a weapon against servitude; in the hands of their inheritors it became a hymn to productivity and national cohesion. This transformation did not occur through conspiracy but through cultural osmosis. The bourgeois state absorbs its antagonists by moralising them. Their words, once instruments of critique, are rendered harmless through commemoration. The statue stands where the barricade once did; the quotation adorns the parliamentary speech. The ghost is invited in so that the living need not remember what it demanded.

Yet beneath this process lies a deeper philosophical irony. Connolly and Larkin were not victims of misinterpretation; they were victims of their own profundity. Each contained within his thought a tension between the material and the moral, the revolutionary and the redemptive. Their socialism was never purely economic; it was an ethical humanism, animated by a quasi-religious belief in the sanctity of labour and the moral community of the oppressed. It is precisely this humanist dimension that permits its conservative afterlife. A doctrine that defines itself in the language of virtue can always be re-invoked by power in the name of order.

The contemporary Irish right does not quote Connolly and Larkin; it channels their moral tone. The appeal to “hard-working families,” to the “dignity of labour,” to “community solidarity” against faceless global forces—all these are spectral echoes of their original rhetoric. What has changed is the direction of the gaze. Where Connolly demanded the overthrow of the system that degrades the worker, the modern conservative exhorts the worker to persevere within it. Endurance replaces resistance; pride replaces protest. The dialectic completes its cruel inversion.

The process by which this occurs may be described, borrowing from Connolly’s own Marxian vocabulary, as the commodification of memory. The revolutionary past becomes cultural capital. The very figures who unsettled order are transformed into emblems of national character. Their faces appear on banners at sporting events, their quotations in schoolbooks and corporate mission statements. The moral legitimacy of the labour movement is thus transferred, through ritual commemoration, to the institutions it once opposed. This is not forgetfulness but a more sophisticated form of remembering: remembrance as domestication.

Connolly once wrote that “the Irish working class are the only secure foundation upon which a free nation can be built”. Today that sentence is cited as patriotic wisdom, its subversive predicate amputated. The “free nation” remains, but the “working class” is no longer imagined as its agent; it has been replaced by the abstract citizen, the taxpayer, the consumer. Larkin’s cry that “a fair day’s work for a fair day’s pay” was not a plea for moderation but a challenge to exploitation itself. In the mouths of modern politicians, it has become a slogan for compliance. The ghost speaks, but its voice is ventriloquised.

If Connolly’s socialism is to be understood in its full philosophical gravity, one must first reject the convenient reduction of his thought to militant economics. In Labour in Irish History, he constructs not merely a genealogy of the Irish working class but a metaphysics of emancipation. The text’s quiet radicalism lies in its refusal to treat labour as a contingent social relation; it is, rather, the primordial mode of human creativity, the site where the species becomes conscious of itself through production. What Connolly inherits from Marx he transfigures through the prism of national experience: the proletarian struggle becomes a moral struggle for the integrity of human being itself, against the mutilations of both empire and capital.

Yet herein lies the ambivalence that history would later exploit. Because Connolly locates emancipation within a moral horizon—because he sees in labour not only necessity but dignity—his dialectic admits a certain pathos. The working class is not simply the agent of revolution; it is the bearer of virtue. In The Re-Conquest of Ireland (1915), the worker appears as the ethical subject of history, whose self-realisation will redeem the nation’s soul. This moral transfiguration of the proletariat, so rhetorically powerful in its time, becomes in later generations the bridge by which conservatism crosses over into socialist vocabulary. The worker, once the revolutionary subject, is reinterpreted as the moral backbone of a stable social order. The “sacredness of labour”, once a cry against exploitation, is repurposed to justify its continuance.

Connolly himself, in his essays for The Workers’ Republic, often warned against this spiritualisation. His insistence that “the cause of labour is the cause of Ireland, and the cause of Ireland is the cause of labour” was not a sentimental formula; it was a structural identity. The political and the economic were, for him, inseparable. But precisely because he couched that identity in moral and national terms, later interpreters could invert it without rupture. The cause of Ireland could, in the absence of class consciousness, subsume the cause of labour entirely. In that inversion—subtle, almost invisible—the revolutionary content dissolves, leaving behind only the ethical residue of nationalism.

Larkin’s corpus, more fragmented and improvisational, nevertheless reveals a similar dialectical fragility. The pages of The Irish Worker are filled with appeals not only to solidarity but to salvation. His belief in the innate nobility of the worker borders at times on metaphysical affirmation. “The working man”, he declared, “is the true creator of civilisation, the image of God in action.” This was not rhetoric alone; it was theology politicised. Larkin’s socialism drew its force from a sacramental vision of labour as divine creativity. But what was born from moral grandeur risks being inherited as moralism. A century later, his invocations of dignity are echoed in conservative homilies on “self-reliance” and “the work ethic”, drained of their insurgent core.

The philosophical mechanism of this appropriation can be traced to what might be called the transcendentalisation of labour. Both Connolly and Larkin, though materialists in practice, sacralised work as a redemptive force. For Connolly, the worker is not merely the negation of capital but its dialectical opposite—the living potentiality of a future in which humanity reclaims its essence. For Larkin, work is the proof of human worth, the visible manifestation of divine immanence. In both formulations, labour ceases to be a site of alienation and becomes the site of possible salvation. But once labour is sanctified, it can no longer be easily criticised. The critique of exploitation is thus displaced by the worship of industriousness. The right, inheriting this sanctification, transforms the socialist hymn into the conservative psalm.

To read Connolly’s The Re-Conquest of Ireland today is to encounter a text vibrating with unresolved tensions. Its central conceit—that Ireland must reconquer itself, not merely from foreign rule but from social servitude—presupposes a unity of moral and political emancipation. Yet that unity, as Connolly knew, is fragile. He writes of the “old order” that “lives by feeding upon the virtue and toil of others,” yet his counter-vision is suffused with the language of purity, sacrifice, and national resurrection. This is the paradox: the same tropes of redemption that animate revolution also furnish the aesthetic of reaction. When the bourgeois moralist later speaks of “national renewal through hard work”, he is unwittingly paraphrasing Connolly’s eschatology, stripped of its socialist predicate.

Larkin’s rhetoric compounds this irony. His famous call—“The great appear great to us only because we are on our knees; let us rise!”—is at once a demand for class assertion and a quasi-religious gesture of resurrection. To rise is not only to rebel but to be reborn. Such imagery carries immense emotional power, but it also lends itself to moral domestication. When modern political discourse celebrates “the rising spirit of the Irish worker” in the context of economic recovery, it participates in this long transmutation of revolutionary resurrection into capitalist resilience.

One might object that such readings impose too much philosophical weight upon pragmatic agitators. Yet Connolly’s prose resists any such simplification. His historical analyses in Labour in Irish History already operate on a dialectical plane, identifying in every epoch the contradiction between the material basis of society and its ideological superstructure. His Marxism, however, is not the abstract logic of Das Kapital but the incarnate Marxism of a colonised people. It recognises that in a nation whose identity has been systematically degraded, the language of morality is the first accessible form of political consciousness. Thus Connolly’s resort to moral and national idioms was not error but necessity—the only available discourse for articulating social totality in a country still bound by the spiritual residues of feudalism and faith.

The tragedy is that historical necessity becomes ideological fate. The moral idiom that once mediated revolutionary truth becomes the veil that obscures it. When the right invokes Connolly’s name to sanctify national unity, it is not distorting his language but inhabiting its unguarded frontier. Likewise, when Larkin’s exaltation of the worker is cited as proof of the dignity of labour within capitalism, it is not a falsified quotation but a displaced interpretation. Their ghosts speak truth still, but truth inverted: the negation of their negation.

If the appropriation of Connolly and Larkin were merely rhetorical, it would not merit the term influence; it would be theft, easily spotted and dismissed. What has occurred in Ireland, however, is more intricate—a subterranean migration of concepts, a smuggling of moral energy from the socialist imagination into the conservative order. The influence operates by concealment. The right could never publicly acknowledge its dependence upon two men who preached syndicalist revolution, yet it has quietly absorbed the emotional grammar through which they made justice legible. The theft was not of doctrine but of tone, of the very affective structure of Irish political speech.

Larkin’s rhetoric provides the first key to this hidden inheritance. His insistence that “the divine is in the worker”, though intended as a heresy against ecclesiastical hierarchy, laid down the template for a later moral populism. In the Ireland that followed, where Catholic social teaching sought to reconcile labour with obedience, Larkin’s theological socialism offered a ready-made emotional vocabulary. The encyclicals that praised the dignity of labour, the sermons that extolled the virtue of toil—all resonated with Larkin’s moral cadence while erasing its revolutionary content. This was the first secret assimilation: the Church, and through it the conservative state, absorbed Larkin’s sacralisation of work and turned it inward, away from class conflict and toward the preservation of order. The worker remained divine, but divinity was now proof that he should accept his lot with grace.

Connolly’s influence followed a parallel, though more sophisticated, route. In The Re-Conquest of Ireland, he had written that true patriotism must be “the outward manifestation of the inner soul of a people at labour”. The line, stripped of its Marxian context, furnished later nationalists with a philosophy of civic virtue. The conservative imagination—especially in the early decades of the state—quietly translated Connolly’s dialectic of class and nation into a theology of productive citizenship. To work was to serve the nation; to question the conditions of work was to betray it. Connolly’s synthesis of socialism and nationalism thus became, in its inverted form, the ideological foundation of a corporatist morality.

It is impossible to trace this transmutation through direct citation, for it was performed in whispers rather than proclamations. The architects of post-independence economic policy, men who would never quote The Workers’ Republic, nonetheless drew upon the same moral horizon that Connolly had inscribed. The rhetoric of “social harmony”, the exaltation of the peasantry as the moral heart of the nation, the portrayal of labour as a duty rather than a right—all bear the spectral imprint of Connolly’s humanism shorn of its dialectic. His vision of a community of producers became, in conservative hands, a myth of the contented smallholder. Thus the socialist republic was transfigured into a pastoral republic, and the revolutionary ideal survived as sentiment.

This hidden continuity explains the peculiar moral tone of Irish conservatism: pious, communal, suspicious of ostentation, yet fiercely resistant to structural equality. It inherits from Connolly and Larkin not their politics but their pathos—the sense that dignity resides in endurance, that virtue is proven through labour and restraint. These are not accidental echoes. They are the residue of a socialist spirituality quietly naturalised within the moral economy of the right. To speak of “the decent man who works hard and asks for nothing” is to utter, unknowingly, a paraphrase of Larkin’s most exalted vision of the worker—now stripped of collective agency and sanctified as humility.

The secrecy of this influence lies also in its psychological function. A political order founded on inequality requires a myth that ennobles submission. Connolly and Larkin supplied, against their will, the materials for that myth. By portraying labour as the site of human nobility, they offered the oppressed a form of transcendence within oppression. The right, recognising the power of that consolation, preserved it while reversing its direction. The moral energy that once impelled revolt was redirected toward reconciliation. The revolutionary conscience became the national conscience.

One finds traces of this transformation even in the rhetoric of twentieth-century state institutions. The glorification of manual labour in schoolbooks, the invocation of “Christian brotherhood” in trade-union arbitration, the solemn celebration of the self-sacrificing worker in political oratory—all these are spectral survivals of Connolly’s and Larkin’s language. They persist because they furnish emotional legitimacy to a society still uneasy with its economic inequalities. The ghosts are useful precisely because they speak the moral truth of labour without demanding its political fulfilment.

This is the deeper secrecy: not that the right consciously borrowed from the left, but that it could not help doing so. Connolly and Larkin articulated the only moral idiom through which labour could be imagined as noble in Ireland; any subsequent politics seeking legitimacy in the eyes of the working class had to speak, however faintly, in their accents. Their influence is therefore not a conspiracy but an inevitability—the subterranean persistence of form after content, of melody after meaning. The bourgeois order that triumphed over their revolution could not silence their music; it merely changed the lyrics.

To name this process is not to expose a hidden plot but to recognise the dialectic of history itself. Every victorious order inherits from the movements it defeats the language of justification. The Irish right, in its moral conservatism and its sentimental nationalism, carries within it the unacknowledged DNA of Connolly’s socialism and Larkin’s prophecy. They are its secret ancestors, the disavowed origin of its moral authority. Their ghosts, having been exorcised from politics, returned as conscience, and in that spectral form, they continue to speak through the mouths of those who once would have silenced them.

In the long twilight of Irish political language, it is no longer clear who speaks in whose voice. Connolly and Larkin, who once embodied the rebellion of labour against privilege, now find their moral universe haunting movements that would have appalled them in life. The far right in Ireland, though clothed in nationalist colours and draped in pious appeals to tradition, has nonetheless borrowed the entire economic and ethical architecture of their socialism. What it rejects is not their programme, but their philosophy of universality—their insistence that the worker’s cause is one with that of all humankind.

This is what makes the inheritance uncanny. The Irish far right, contrary to the caricature of being simply capitalist or reactionary, is profoundly socialist in its economics. It believes in the sanctity of labour, in the moral worth of the producer over the speculator, in the duty of the state to defend its people against global finance. It has reabsorbed Connolly’s central conviction—that capitalism, not poverty, is the true enemy of the nation—yet replaced the vocabulary of class with the vocabulary of belonging. In doing so, it has carried Connolly’s analysis into its own camp, even while declaring itself his opposite.

Connolly wrote that “a free nation can only be built upon the ownership by the people of the land and instruments of production”. The far right repeats this in translation: that Ireland must own its soil, its food, its energy, its labour—that the nation must be self-sufficient, independent, and unenslaved to the abstractions of global capital. But where Connolly’s “people” meant the working class as a universal community, the far right’s “people” mean the nation as a bounded one. The moral structure is the same; the subject has been replaced.

Larkin’s faith in the redemptive power of collective struggle, his insistence that “the great appear great because we are on our knees”, echoes again in the rhetoric of the new nationalists, who speak of rising, of standing tall, of reclaiming destiny. The grammar of rebellion survives intact. The far right’s appeals to solidarity, to social unity, to the sanctity of work and family, all mirror the socialist gospel of dignity through labour. The only difference lies in the metaphysics: for Larkin, man was redeemed through solidarity with other workers; for the new nationalist, through solidarity with his own.

Economically, their project is not capitalist in the orthodox sense. It does not worship the market or seek the supremacy of private accumulation. Rather, it imagines a state-organised socialism of the nation, where production serves the moral and cultural identity of the people. This is not laissez-faire, but dirigiste; not libertarian, but collectivist. The capitalist is distrusted; the worker is revered. The financial class, the technocrat, the cosmopolitan merchant—all play the same role in their mythology that the bourgeoisie played in Marx’s and Connolly’s. The far right’s socialist inheritance lies in its anti-capitalism, in its vision of a moral economy purged of exploitation and decadence.

And yet, the refusal to name this socialism—to claim Connolly or Larkin as forebears—reveals the ghost’s power. They cannot disavow the economic logic they have inherited, but neither can they embrace its international soul. They stand in the shadow of the very tradition they deny. To call themselves socialists would be to confess kinship with communism; to call themselves capitalists would be to betray the worker. And so they live in the spectral space between, haunted by the dialectic they cannot resolve.

In truth, their economics cannot be made distinct without returning to Connolly. His socialism, stripped of its class universalism and its revolutionary humanism, becomes precisely the system that animates the far right today: socialistic in structure, nationalist in scope, moral in tone, but exclusionary in definition. The economic system is collectivist; the political system, authoritarian; the moral system, puritanical. What remains of Connolly is the conviction that labour is sacred, that capital is parasitic, that the nation must be built from the bottom up, but the internationalist heart of that conviction has been removed.

Thus, when one listens closely to the modern right-wing invocation of “the Irish worker”, “the ordinary man”, “the small farmer and tradesman”, one hears the voice of Connolly in disguise. His words have been inherited not by his comrades but by his opposites, yet they could not have spoken without him. The irony is philosophical: they cannot escape Marx, Connolly, or Larkin, for their very logic—their social theory, their distrust of liberal capital—was built by them. They are socialists who refuse the word, inheritors who deny the lineage, moral collectivists who insist on being called nationalists.

It is this paradox that animates Ireland’s newest ghosts: those who walk in Connolly’s shadow while claiming to oppose his light. They have not overthrown the left; they have absorbed it. The far right does not reject Connolly and Larkin; it is built from them, brick by brick, sentence by sentence, dream by dream, until the socialist republic has been remade as the nationalist one. The ghosts have found new hosts.