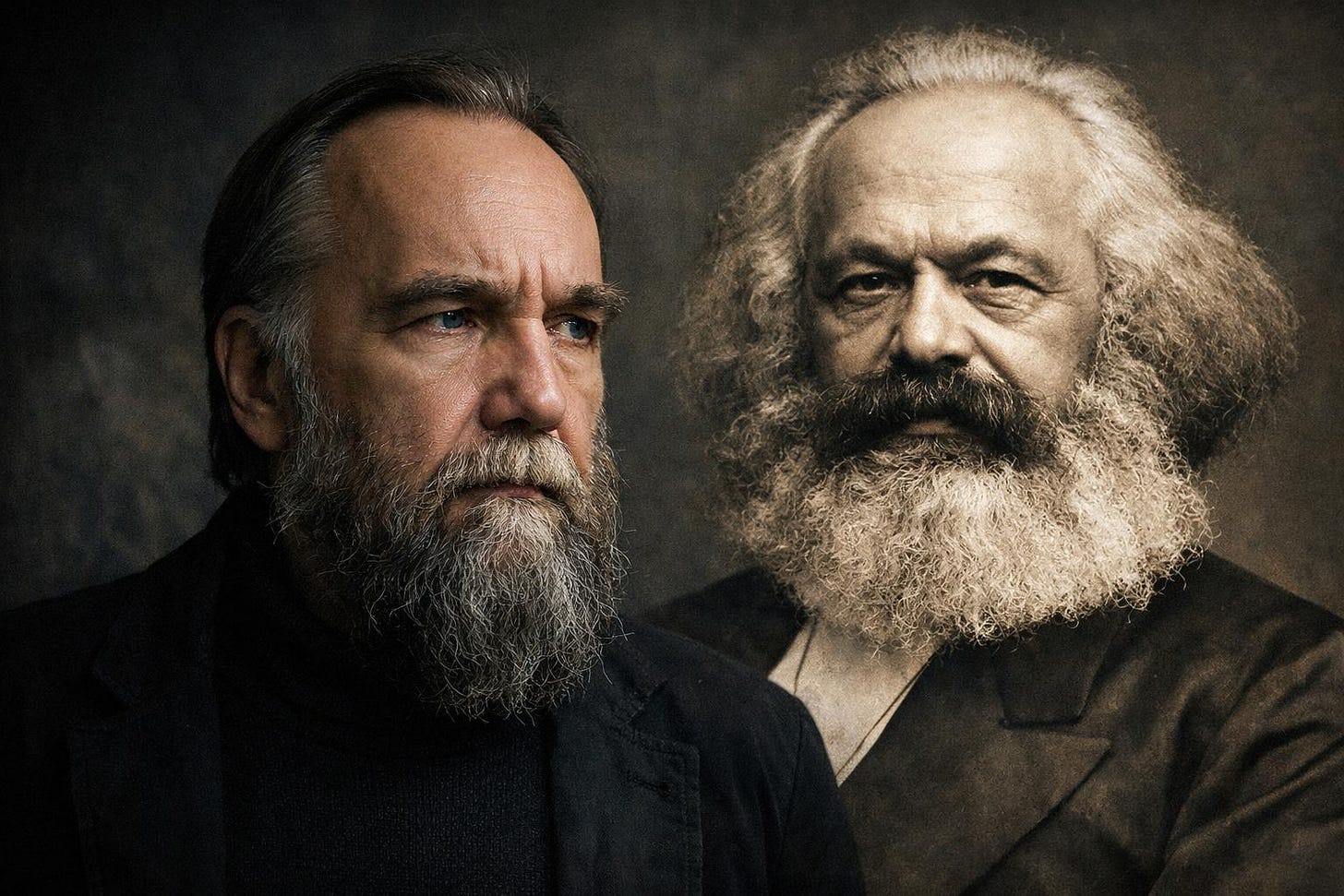

Master and Slave: The Fatal Error of Marx

Why Marx misunderstood Hegel

Alexander Dugin argues that Marx misread Hegel, mistaking an eternal structure of consciousness for a historical problem that could be abolished.

The model of the relationship between Master and Slave was examined in detail by Hegel. There is an interesting moment within it. In fact, Marx built his doctrine of revolution on this very passage. The Master struggles, preferring death and freedom (that is, for him freedom and death are one and the same), while the Slave chooses not freedom, but slavery and life. Whoever chooses life chooses slavery; whoever chooses death chooses freedom. Thus death, freedom, and mastery form one side, while life, survival, material production, the processing of beings, and slavery form the other.

In this way, two philosophical types emerge. Note that we are speaking of philosophical types. Of course, the temptation immediately arises to apply this to sociology, anthropology, ethnology, the structure of society, and classes. Marx did exactly that: he posited masters and slaves and the idea of a slave uprising. Marxism is built on the premise that the slave has no consciousness of his own, and therefore the exploited masses of feudal society (or an even more ancient one) live not by their own consciousness but by the consciousness of the ruling class. They do not know themselves, becoming aware of themselves only through the consciousness of the masters. They lack self-consciousness, while the masters possess it.

Hegel goes on to say that in the battle with death, and in the battles of death itself with its reflections and echoes, the Master does not attain immortality in the full sense of the word, although that is precisely what he seeks. Instead, he acquires the Slave. The one who fled from him, who could not withstand his emptiness and his gaze, becomes his prey. And the Slave, having become a Slave, gains the opportunity not to look into the eyes of his master, to lower his gaze—that is, not to look death in the face—and accordingly he gains life, although he is no longer free. And what does freedom mean? For Hegel, freedom is self-consciousness, and only self-consciousness is freedom. Whoever is free is conscious of his own consciousness—Selbstbewußtsein. Whoever is unfree does not recognize his selfhood: this is precisely what unfreedom is. Freedom has no other parameters. Social position, for example that of dependent exploited classes or ruling classes, is merely the consequence of the realization of certain philosophical orientations and movements that occur within the subject. The subject who insists on his self-consciousness to the very end either perishes or becomes dominant. The subject who evades this resistance, who withdraws from it, swells the masses, as the Polish Sarmatists or the Hungarian adherents of Scythian ideology believed.

In philosophy, especially in Hegelian philosophy, all of this is impeccable. Of course, in history, sociology, and anthropology one can find both confirming and refuting examples. There is no direct projection of these principles onto the history of human societies. Yet these profound observations require careful reflection; they should not be applied immediately. Marx attempted to apply them, but as soon as he erred slightly in the subtleties of philosophical models, failing to think Hegel’s idea through to the end, many of his notions about the social nature of the processes unfolding in human society throughout history proved incorrect and mistaken.

The Hegelian dialectic of Slave and Master pertains above all to the structures of the subjective Spirit. From it one may draw

the conclusions drawn by Marx,

the conclusions drawn by Gentile,

and the conclusions drawn by Heidegger.

If the philosophical topography is correct, it possesses an unlimited number of applications, versions, nuances, refutations, and confirmations. At the same time, it is entirely independent of its applied aspects. The truth of philosophy is verified not by experiment but by full immersion in its structures and by the skill of freely navigating them, cautiously correlating them with other metaphysical systems.

In any case, whoever renounces freedom renounces self-consciousness. And whoever renounces self-consciousness is immediately placed on the periphery of society, which is logical. The Slave’s consciousness is directed outward, toward the sensory world, toward sensations, toward that semblance (Schein) that passes itself off as being. Not toward the phenomena themselves, because phenomena reside within the Master, and in order to break through to them one must first break through the immense power of the negative. In general, phenomenology is the business of Masters, because to confront the movement of thought—especially reflection, the movement of consciousness into itself—means, for Hegel, to gain the experience of contact with the sphere of the first supersensible world, where the phenomenon reveals itself as phenomenon: Erscheinung als Erscheinung. Only the Master can permit himself this, for he moves toward his own mastery within himself. Since Erscheinung as phenomenon is the affair of the subject, phenomenology itself is the affair of Masters, not Slaves. The Slaves’ affair is sensory perception—consciousness without self-consciousness. The philosophical Slave is destined to be an instrument, an intermediate zone within human culture, a border territory between the masterly center and the world of externality, a zone of negative objecthood that disintegrates and disperses as it recedes from the center of radical subjectivity along the scattering rays of diminishing essences.

Thus the Master, having acquired the Slave, concentrates on the inner content of consciousness, on apperception, on phenomenological reduction, on the problem of cultivating the royal Radical Subject. The Slave, by contrast, is sent to the periphery of consciousness in order to organize sensory experience. There he passes into direct interaction (to speak in Kantian terms) with the a priori forms of sensibility—with space and time, with the most external aspects of being. The Slave produces things because he cultivates them. Of course, he is the bearer of an important, rational consciousness. He arranges and orders things; he produces them, while the Master merely consumes or destroys them. The Slave provides the thing to the Master so that it may cease to be. The Master says, “Bring me this or that; I will now consume or destroy it.” The Master consumes whatever he wishes, since he effectively appears as the destroyer of all that exists and that he himself does not create. The Slave creates everything; the Master only annihilates. Either in war, to which he is naturally drawn, or outside of war—the Master is engaged in destruction. The naïve notion that the Master must be kind, helping his workers (or laborers) paint walls, for example, is hardly realistic. The Master should concern himself with nothing; he must be absolutely free from any prescriptions, and above all from the prescriptions of what Slaves think, because Slaves must do what the Master tells them, rather than approach him with their own considerations.

Such is the dialectic of Slave and Master. One can also observe their differing relation to production: what the Master destroys or consumes, the Slave creates. This impressed Marx, and he decided that at some point the Master would gather many slaves (an entire class), subjugate them, and consume only what they produced. Accordingly, at some moment the Master would become dependent on the slaves, because if he had nothing to destroy—that is, to consume—he would vanish, perish. Then it would turn out that the slaves, useless in themselves, had become vitally necessary to him.

Yet even if we allow that this will not occur (contrary to Marx), and if the Master’s self-consciousness becomes absolute self-consciousness, dependent on nothing—including the class of slaves that supplies it with ontic content—it would become a concentration of black negativity, a radical negation annihilating all that exists. Even the illusion of the nicht-Ich would remain no more, and consequently there would no longer be any subordinate, slavish world subject to destruction by consciousness—that is, to comprehension or knowledge.

In Hegel, the discussion concerns the structure of consciousness given to us synchronically. The phases of the battle between two self-consciousnesses—the heroic struggle with death and the desertion that turns the warrior into a Slave, the preference for life at the cost of renouncing self-consciousness—are described as sequential. Yet in Hegel’s structure they are synchronous. These are structural moments within the field of consciousness. It would be entirely mistaken to interpret this from the standpoint of temporal succession. What is present here is a logical, not a chronological or diachronic sequence. To assume, as Marx did, that a moment will arrive when the Master becomes overly dependent on the Slave, that the Slave’s own self-consciousness will awaken and he will realize that the Master can neither eat nor drink without him, and that the Slave, entering into his consciousness, will destroy the Master and his nihilistic will, halt his striving to consume and annihilate, and create a beautiful world of the laborers of socialism and communism—this is theoretically possible. The liberal Hegelian Kojève saw the resolution of the Master–Slave dialectic in civil society, although Hegel himself considered it possible only in a fully realized State of the future—in a constitutional monarchy.

Nevertheless, without a careful structural analysis of consciousness and a clear understanding of the nature of self-consciousness, we risk obtaining not genuine but inverted Hegelianism—a Hegelianism turned upside down. Marx’s idea that proletarian consciousness will recognize the Master’s dependence on the workers, cast off the borrowed masterly self-consciousness, overthrow the power of the exploiting classes, and build a society without negation, without negative consciousness—founded on pure constructiveness and sensibility, without that terrifying masterly subject who constituted the essence of the fundamental problem in the relation of Slave and Master—proceeds from a deeply false understanding (if not outright rejection) of the subjective Spirit and its structures, to say nothing of the Radical Subject.

Ultimately, if we adopt Marx’s position and take the side of the Slave who seeks liberation from the Master, it is tantamount to acknowledging that consciousness can exist only as its own periphery without a center—that there is no center at all and that none is needed, since from it emanate only various terrible impulses, chief among them death. The logic of the Marxists is as follows: if one ignores the inner content of consciousness and clings to external being—or even further outward, into the domain of Husserl’s “natural attitude,” beyond the bounds of consciousness—only then can happiness, immortality, and equality be attained, and the Middle Ages, exploitation, and domination be ended forever. Extending this line to its logical conclusion, we arrive at the inference that in such a case there would remain not only no philosophy and no Radical Subject, but ultimately no human being at all.

Therefore, it is extremely important to conceive all phases and stages in the formation of the pair of Master (as subject and bearer of self-consciousness) and Slave (as bearer of subordinate consciousness) as an immutable—in a certain sense “eternal”—configuration of the anthropological structure. In this sense, a synchronically understood (read) Hegel can be applied to ancient, medieval, and modern societies alike. Sometimes this appears vividly, sometimes in veiled form (for example, through various procedures of civil society, where a direct claim to absolute mastery is no longer encountered), yet domination itself—and here Marx is precisely right!—does not disappear in democracy and civil society, in capitalism; on the contrary, it becomes only more total. In any case, if one looks closely at such societies, the axis of Master/Slave will inevitably reveal itself. Behind all the claims of modern democracy to equality—that at last the slaves have seized power and abolished hierarchies, that there are no longer masters over them, and accordingly that slaves are no longer slaves but respected members of “civil society”—there lies an entirely different picture, far closer to the Hegelian pair. The ruling elites of democracy—especially under conditions of globalism—strive more than ever for total control over the consciousness of the masses, projecting their will onto it, burdening it with false surrogates, and mercilessly “canceling” any attempt by the masses to awaken and call the ruling (most often liberal or left-liberal) ideology into question. In liberal society, another edition of the Master stands in place of the ruling class: he bears a different name, looks different, is newly styled. Yet domination cannot be abolished without abolishing the human being, without destroying society, without annulling thought and philosophy. The absence of domination would require the absence of the human.

Postmodernism, or the posthumanist current in culture, gradually arrives at such a radically egalitarian conclusion. Liberation from hierarchy is possible together with liberation from the human. Where there is a human being, differentiation between slavery and mastery will inevitably arise at some level, even within one and the same entity. Hence the verticality of the human; hence the domination of the mind (the head) over the other organs. Indeed, everything connected with the human is the history of the dialectic of Slave and Master, in principle not subject to major change throughout the entire period of humanity’s existence. Yes, it unfolds in different forms and combinations, yet masters and slaves—in various forms, combinations, under different masks, with different models of institutionalization—always exist, whether they know it or not, whether they acknowledge it or not. Slaves may not suspect that they are slaves, but masters always operate with a more responsible picture, though they often conceal it, distort it, or even deny its existence.

A. G. Dugin

Hegel’s Phenomenology — An Experience of Transversal Interpretations

Academic Project, Moscow, 2024

(Translated from the Russian)

No, Marx was right to relativise the polarities of class struggle in order to posit the unified destiny of the otherwise polarised psyche naturalising intra and extra psychic bourgeois neurosis ad armageddon.