Divide and Rule: America’s Rimland Strategy

Why America fears Eurasia more than anything else

Brecht Jonkers explains that nearly all of US foreign policy since 1945 follows Nicholas Spykman’s Rimland thesis, itself rooted in Mackinder’s Heartland theory, which has guided successive imperial strategies to divide Eurasia and secure American global dominance.

In order to understand pretty much all US foreign and military policy since World War II, you should study the Rimland Thesis by Nicholas Spykman. Spykman wrote the basis for US geopolitical strategy back in the 1940s, one which was subsequently taken over by the Pentagon, the State Department and the CIA as the blueprint for post-war US expansionism.

Spykman based himself on the Heartland theory of British strategist Halford Mackinder, stating that at the core of the World-Island (encompassing Eurasia and Africa) was the so-called Heartland: the impenetrable landmass corresponding roughly to the old Russian Empire.

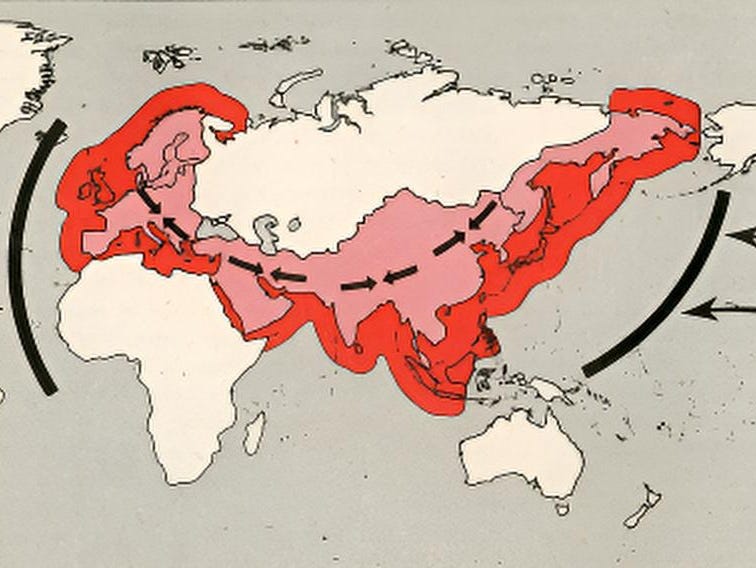

However, Spykman went further and posited that the true region of crucial strategic importance in the world was the so-called Rimland: the vast, interconnected region surrounding the Heartland and connecting it to the coastline. The Russian landmass may be the quintessential land power, but Spykman claimed it would be wrong to see this realm as the major scene of world-changing events. The pivotal area, the Dutchman claimed, was the Rimland: the massive region facing both the Heartland and the coastline, and extending from coastal Europe across the entirety of West Asia, the Indian subcontinent, Southeast Asia, and up to and including China, Korea and Japan.

This massive stretch of land contains the vast majority of the world’s population, most of history’s major ancient cultures and civilisations, and the largest deposits of natural wealth globally. It is also a dual-identity region, which combines the land-based imperial history of the Eurasian landmass with the more mercantile and adaptable seaborne networks.

Nicholas Spykman summarised his key principle in the following maxim: “Who controls the Rimland, rules Eurasia, who rules Eurasia controls the destinies of the world.”

The United States is by definition an “insular” power in this equation, meaning it is positioned away from the World-Island and the heart of the world, and has to rely on naval military might and active power projection if it wants to play a role of importance. Just like Britain in the past, the US has no natural connection to the main theatre of world history, being positioned in an isolated position compared to the Heartland and Rimland alike. This necessitates a far more active, and aggressive, foreign policy if any hegemonist agenda is to be fulfilled.

The main “threats” to US domination in the Rimland in Spykman’s theory are the continental land-based powers like the Soviet Union and China. Therefore, it is to the utmost importance for the US imperialists — through a policy of “offshore balancing” — to keep the Rimland divided and prevent any Eurasian power from achieving dominance in the region.

Nearly all of US foreign policy in the Asia-Pacific region since 1945 fits into the wider policy detailed by Spykman, further developed by people such as John Dulles and his brother Allen Dulles, Zbigniew Brzezinski and Henry Kissinger.

The Dulles brothers, State Secretary John Dulles and CIA Director Allen Dulles, explicitly used Spykman’s thesis as the blueprint for their “massive retaliation” and “rollback” principles that resulted in major imperialist intervention in Asia. This included the 1953 coup in Iran and their aggressive attempts to contain the USSR through a series of satellite states and military alliances, such as the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (1954-1977) and the Baghdad Pact (1955-1979).

State Secretary Henry Kissinger took several pages from Spykman’s book when he urged the Nixon administration to try to play off China against the Soviet Union in an attempt to ensure neither of the two Eurasian powers could gain a lasting foothold that could challenge US hegemony. National Security Advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski was even more blatantly aggressive in his application of Mackinder and Spykman, and made it his own personal goal to stir up as much trouble as possible across the Rimland to ensure maximum damage to the Heartland power that was the USSR. From pushing President Carter to emphasise West Asia and the Arab world as a focal point of US foreign policy, to arming Afghan rebels to get the Soviet forces mired in an unwinnable war, Brzezinski was as relentless as he was open in his intentions.

As the man of the “Grand Chessboard” theory said it himself in 1997: “America’s global primacy is directly dependent on how long and how effectively its preponderance on the Eurasian continent is sustained.”

In other words: Eurasian dominance is of supreme importance to US foreign policy. Or, if that should prove to be impossible: a maximum amount of chaos and infighting is to be fomented on the World-Island in order to ensure that no continental power could ever create a stable challenge to US domination.

From the hub-and-spoke policy of allied states such as Japan, South Korea and Taiwan, to the containment policy behind the Korean War and the domino theory justifying the war against Vietnam: it all fits in the idea of divide-and-conquer in the Rimland with the double goal of maximising US power in the region while trying to deny dominance to any actual Rimland or Heartland power.

Even today, the Pivot to Asia and the turn against China are a textbook application of the Rimland theory: China as a quintessential Rimland power is ideally placed to throw a wrench into the insular thalassocratic (sea and naval power-based) American plans for domination of the World-Island. Therefore, countering Chinese economic and military might has become one of the biggest priorities for US foreign policy in this day and age. Through economic warfare like sanctions and trade tariffs, through constant propaganda, through fostering ethnic strife and separatist agendas in Xinjiang, Tibet and Hong Kong; the US hegemonic agenda against China is being carried out as we speak. Combined with military posturing near Taiwan, the establishment of new military partnerships such as the Quad, the attempts to draw India into an anti-Chinese alliance and the attempts to link Asia with the NATO system in Europe through connecting hubs like Georgia and Azerbaijan: it all is part of a much wider and much longer policy that stretches across generations.

The United States is, for all intents and purposes, the successor of the British Empire: a highly aggressive and expansionist thalassocratic power that sees itself as being directly in opposition to the cultures and civilisations of Eurasia. An imperialist hegemon that cannot abide “competition”, even when it is half a world away and far removed from American soil. It is the legacy of Nicholas Spykman, and through him that of Halford Mackinder, that looms large over the State Department, the CIA and the Pentagon up to this very day.

The world has changed considerably since Brzezinski and Spykman. The BRICS nations have a strong positional advantage on the Giant Chessboard. A shared hegemony seems the only sensible strategy for the U.S. China’s Belt and Road and the solidification of new partnerships in the Indo-Pacific have turned the Rimland into an arena of active rivalry and cooperation. If ever there were a time to make the morally correct sacrifice of a few pawns and bishops and to allow multipolarity, that time is now.

The problem with American empire is that it pumps out deceptive propaganda to keep the citizenry in the dark about this. American empire doesn’t help the citizens but only the same monopolistic corporations and banks that take all the benefit on the people’s dime. This harks back to Smedley Butler and his book War is a Racket where he exposed how as a Marine he didn’t fight for the interests of the American people but rather corporate interests.