Art and the Common Man

Universality as the safeguard of literature’s true essence

Chōkōdō Shujin stresses that literature must seek universality beyond vulgarity to reach true artistic value.

The issue I seek to address at present is not limited to the realm of literature, but is also concerned with the vulgar nature of modern artistic works, and how this relates to their apparent popularity.

The distinction between vulgarity and popularity needs to be made more clearly, but for simplicity’s sake, vulgarity refers to the inclusion of elements that stimulate cheap interest and emotion in the general public, who lack artistic culture. There has always been a certain element of society that lacks the capacity to perceive beauty, purity, and nobility. This cannot be helped, but nonetheless, such people are not to be catered to. Often, they prefer vulgarity and ugliness, and well-written literature would be wasted on them. Popularity does not refer to the masses in this sense, but rather to something that aims for the aspirations and tastes of a certain social class, and is primarily comprised of simple and clear artistic elements that appeal to the healthy sensibilities of human beings. Popular works are not without value.

However, just as an attempt to be popular can lead to vulgarity, the tragedy that often results from being overly and deliberately vulgar is that it is not popular, and at the same time, it loses its true universality. From what I have observed, there are still many individuals who abhor vulgarity and the various cheap literary tricks designed to appeal to those lacking in taste or refinement. Simply put, the average man has an innate, reflexive aversion to that which is truly vulgar.

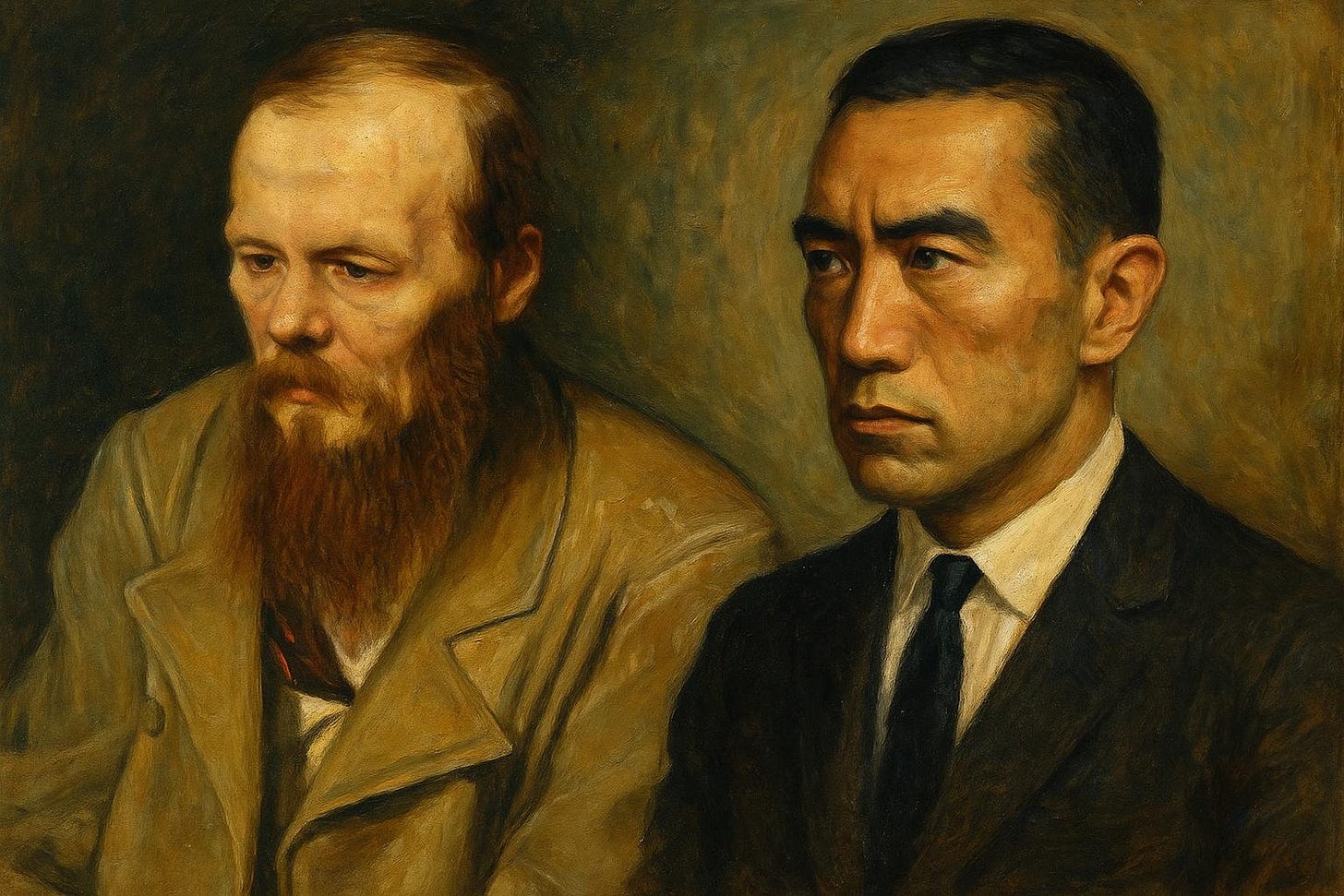

While it is true that many lofty works lack universal appeal, this effect is something that the author intends to achieve. Many of the novels of Yukio Mishima or Sōseki Natsume, for example, were never designed to appeal to the masses. The Double by Dostoevsky is an exceptionally fine example of such a piece. Not everyone can appreciate such a work. Still, a certain level of taste is something that can be cultivated in most people with any degree of intelligence. It is obvious that such individuals must be the intended audience for the majority of literary works. However, those involved in the literary world should be aware of the fact that, despite the clearly stated intention to appeal to the widest possible audience, the results are often contrary to this.

While I have nothing to do with commercial literature, I do deplore the tendency of today’s modern fiction, striving to cultivate a wider audience and consciously striving for vulgarity in an attempt to appear cosmopolitan. Of course, if the works were completely vulgar, they would not be popular, but I believe that anyone who takes on the role of an artist must in some sense be saved from vulgarity.

Most writers to date have certainly narrowed the scope of their audiences in their choice of subject matter and in the unnaturalness of their plots. However, in order to broaden the scope of the audience, we must first seek universality in literature. Popularity is fine, but the public does not seek “art” at this time, nor is there any momentum towards such a desire. In short, it cannot be helped.

However sophisticated the artistic quality, I believe that universality is enough to gain supporters for the current literary movement.

So, what is universality? It is not necessarily what one would call the masses, but it is the average person with an ability to appreciate beauty who seeks a genuinely vivid and finely written novel, rather than a mere model of something new. It is an element that unconditionally attracts an audience who, while not interested in pioneering literary endeavors or the writer’s particular state of mind, are moved by the beauty and truth of the story, and who, while unaware of the writers’ backgrounds, can nonetheless discern their talents.

The universality of the piece should be sought in the author’s intellect, while the charm, as it were, should be sought in the author’s distinct personality and temperament. To put it rather simply, until now, much of highbrow literature has become “literary, all too literary,” as Ryūnosuke Akutagawa famously put it nearly a century ago, and suitable only for literary enthusiasts, with perhaps too much emphasis on technique, and in many cases, ordinary people cannot understand what is interesting about the work.

This is most evident in the works of writers who seek to be avant-garde, and various new styles of literature claiming to be “modern” — be they written in the 1920s, 1960s, or today — show this malady in stark contrast to the “popular” writing of the day. Some time ago, I read a melodrama called The Double, which showed the talent of José Saramago as a writer. Even so, it was a mere rehearsal of literary techniques, and I was taken aback. Not only was it tedious, it was simply unpleasant to read. Beyond this, the piece shares a title with the aforementioned novella by Dostoevsky, who accomplishes the same unreliable narrator technique without flaw. Although Mr. Saramago may have had other intentions, in the end I thought it was poor as a campaign for baroquely written literature, and too professional to be a popular novel. It is a difficult task to keep it fresh and universal, but for the sake of the future of literature, we must not rush to achieve success.

The “experts” among the writers must be able to avoid the taste for modern literature and create archetypes of characters from all strata of society without falling into poorly executed naturalism. It is not merely a matter of character, but also a matter of training to grasp, through observation and imagination, what makes a businessman a businessman and what makes an artist an artist. This is, first of all, a matter of cultivation as an author.

Very few of today’s writers can depict the role of a so-called upper intellectual class character. At the same time, there is no one who observes the so-called bourgeoisie. No soldiers, no diplomats, no police deputies, no sophisticated society ladies, no modest housewives. Age is certainly a strong factor. But more than that, their lives are too narrow, their culture too poor, and their powers of observation insufficient. In other words, this is the cause of the lack of universality in their works. This is where the phenomenon of their audiences being exclusively other literary sorts arises.

It is fair to say that Japanese literature, too, is currently making various efforts to address this issue. It is time for writers to consider what makes their work so narrow. We must break the delusion that something is “highbrow” because it is “narrow.” Narrowness does, in a sense, speak of purity, but purity does not necessarily create value in itself. Beauty and nobility must also be present, as both Yukio Mishima and Sōseki Natsume distinctly wrote.

On the one hand, it is fine for there to be works that are only accepted among specialists. However, that alone does not constitute all excellent art.

I have only ever discussed the issue of pure literature as a research measure for specialists. It is for the development and self-sustenance of modern literature that I now advocate the universality of the work. Furthermore, it is my theory that the essence of literature must go through a process of purification, and that its universality must be derived through the accurate assimilation and utilization of that essence.

It goes without saying that when literature and all of the other arts move in the direction of popularization, they begin to turn their backs on their essence. But is it also not true that the methods chosen to popularize literature often result in the abuse and overemphasis of “non-literary” elements?

Thanks for your great work!

We've shared this link on 'The Stacks'

https://askeptic.substack.com/p/the-stacks

It is a mistake to think that the highest function of literature is to be clear and easily digested by the so-called “average reader.” If an author begins with that as his guiding aim, he has already renounced the essence of literature. Literature is not journalism, nor is it popular entertainment. Its responsibility is to truth, beauty, and form — all of which often resist simplification.

History shows us that the greatest works were never designed to accommodate mediocrity. Shakespeare did not write for the “average man,” he wrote out of the fullness of genius — and the public rose up to meet him. Likewise, Dickens’ novels did not become powerful because they were simplified, but because they were uncompromising in their emotional and social depth, which happened to resonate across classes. When we turn to Proust or Joyce, we see another path: works that may be daunting, but which reveal new dimensions of consciousness and art. To dismiss them as unreadable is to confuse difficulty with worthlessness. Art that endures often requires patience, discipline, and cultivation.

The insistence that authors “write simply” in order to instruct or entertain reduces art to pedagogy. The great writer is not a schoolmaster but a creator of worlds. His task is not to tell the reader what he already knows, in familiar words, but to expand his horizon — sometimes painfully. This is why Mishima, Dostoevsky, and Sōseki retain their authority: they confront us with truths we cannot encounter in popular forms, even if their readership is narrower as a result.

Universality should not be confused with accessibility. True universality means that the work speaks to the essence of human experience, but the reader must cultivate himself in order to receive it. Beethoven’s late quartets are not understood by a first-time listener, yet they remain universal. Likewise, the responsibility lies with the reader to rise up to the work, not with the author to lower himself.

If we accept that literature must always aim at the average reader, we condemn it to mediocrity. We would flatten Shakespeare into a pamphlet, Dante into a sermon, Joyce into a newspaper column. The duty of the writer is not to please the crowd but to preserve the dignity of art. If, in doing so, he wins a wide audience, so much the better; but if not, his work still endures as a beacon for those who are willing to climb to its height.