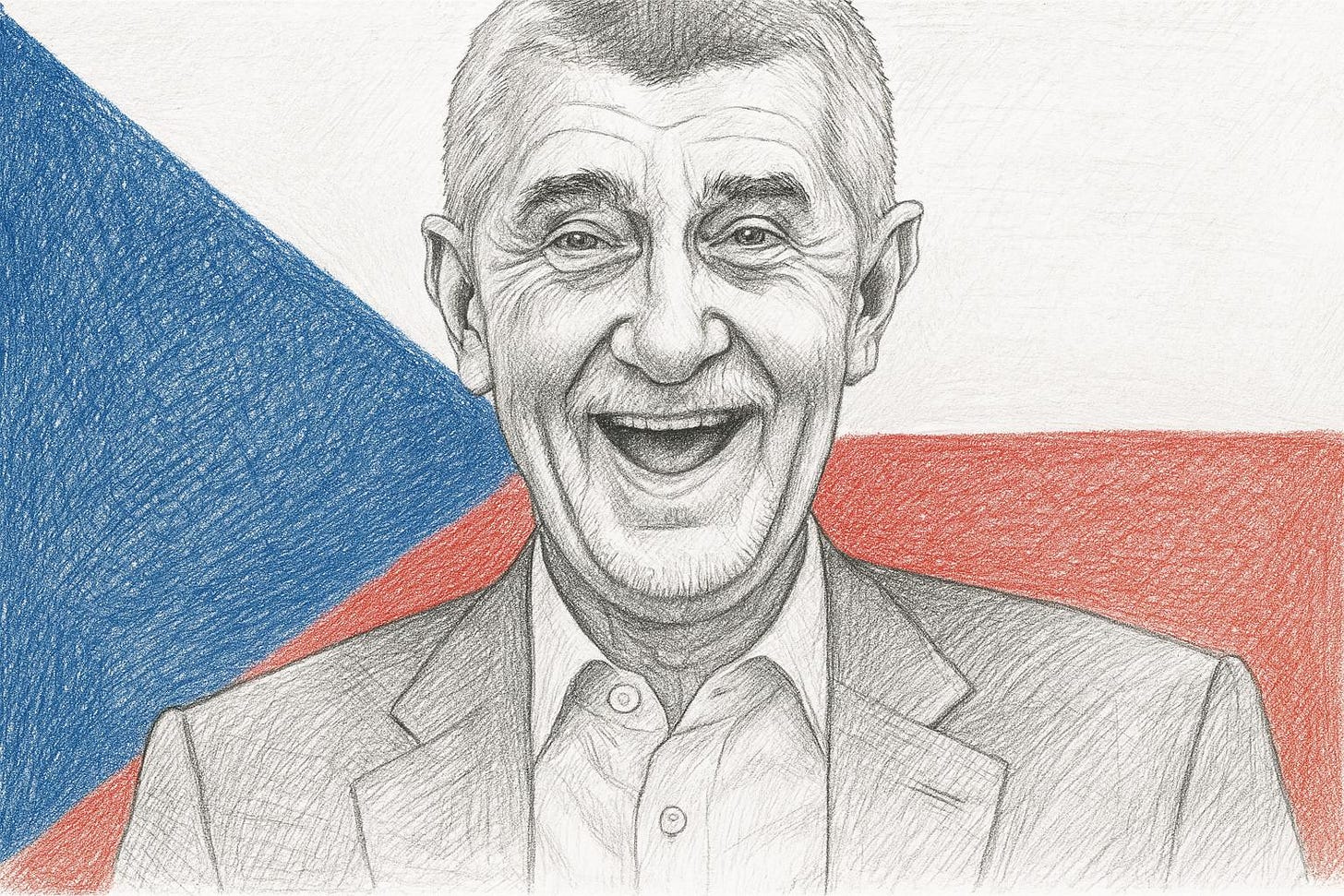

Andrej Babiš Dominates Czech Parliamentary Elections

A Czech comeback signals shifting power in Central Europe and a challenge to Brussels.

Kenneth Schmidt analyzes Andrej Babiš’s decisive election victory in the Czech Republic and its potential to reshape Central European politics and unsettle Brussels.

In what can only be described as an extraordinary political comeback, right-wing populist Andrej Babiš and his party, the ANO, came out on top in the Czech parliamentary elections held on the 3rd and 4th of October. Mr. Babiš, who had served as prime minister from 2017 to 2021, when he was defeated in an election, gained eight seats above the 2021 contest and got 34.5% of the vote.

It appears quite likely that Babiš will become prime minister by ruling in coalition with two small right-wing parties, one is the MOTOR Party, an anti-environmentalist group that opposes Green policies and fights for the rights of car owners. Since its founding, MOTOR and its leader, Petr Macinka, have broadened their appeal to include anti-liberal positions and Euroscepticism. Also, another probable coalition partner is Freedom and Direct Democracy (SPD), which is a party that is generally considered to the right of Babiš’ ANO. SPD has close ties to National Rally in France, Lega in Italy and the Austrian Freedom Party. What I find amusing is that the party is led by a gentleman born in Japan, Mr. Tomio Okamura!

Why did Mr. Babiš and ANO win? The center-right, globalist government of Petr Fiala had done a poor job of controlling inflation, which has caused growing frustration among ordinary Czechs. In the midst of economic suffering at home, the Fiala administration was spending huge sums in purchasing weapons for the Ukrainians in their war against Russia. Babiš made a campaign promise that he would make significant cuts in Ukrainian military aid. It is likely that a new ANO government will take a tougher stand against Brussels on green policies and migration issues. Mr. Babiš campaigned hard. He bought himself a recreation vehicle and went from town to town giving speeches, and this method seemed to have worked well for him.

The geopolitical issues surrounding the Czech election are significant. If Hungary’s Orbán manages to stay in power, it is considered likely that an informal alliance will be formed between Orbán, Babiš and Prime Minister Fico in Slovakia to keep a lid on the possibility of Britain, France and Germany ginning up a shooting war against the Russians. My only worry is that the election in Hungary, set for April 2026, is likely to be tight. A few months ago, polls seemed to indicate that Orbán’s Fidesz was going to lose. Fortunately, Fidesz has since recovered a lot of its support, perhaps because ordinary Hungarians are not interested in war. Still, what will actually happen on election day in Hungary is still an unknown factor.

Thanks for your great work Kenneth!

We've shared this link on 'The Stacks'

https://askeptic.substack.com/p/the-stacks

I am still thinking Ukraine will become a Jewish fortress!