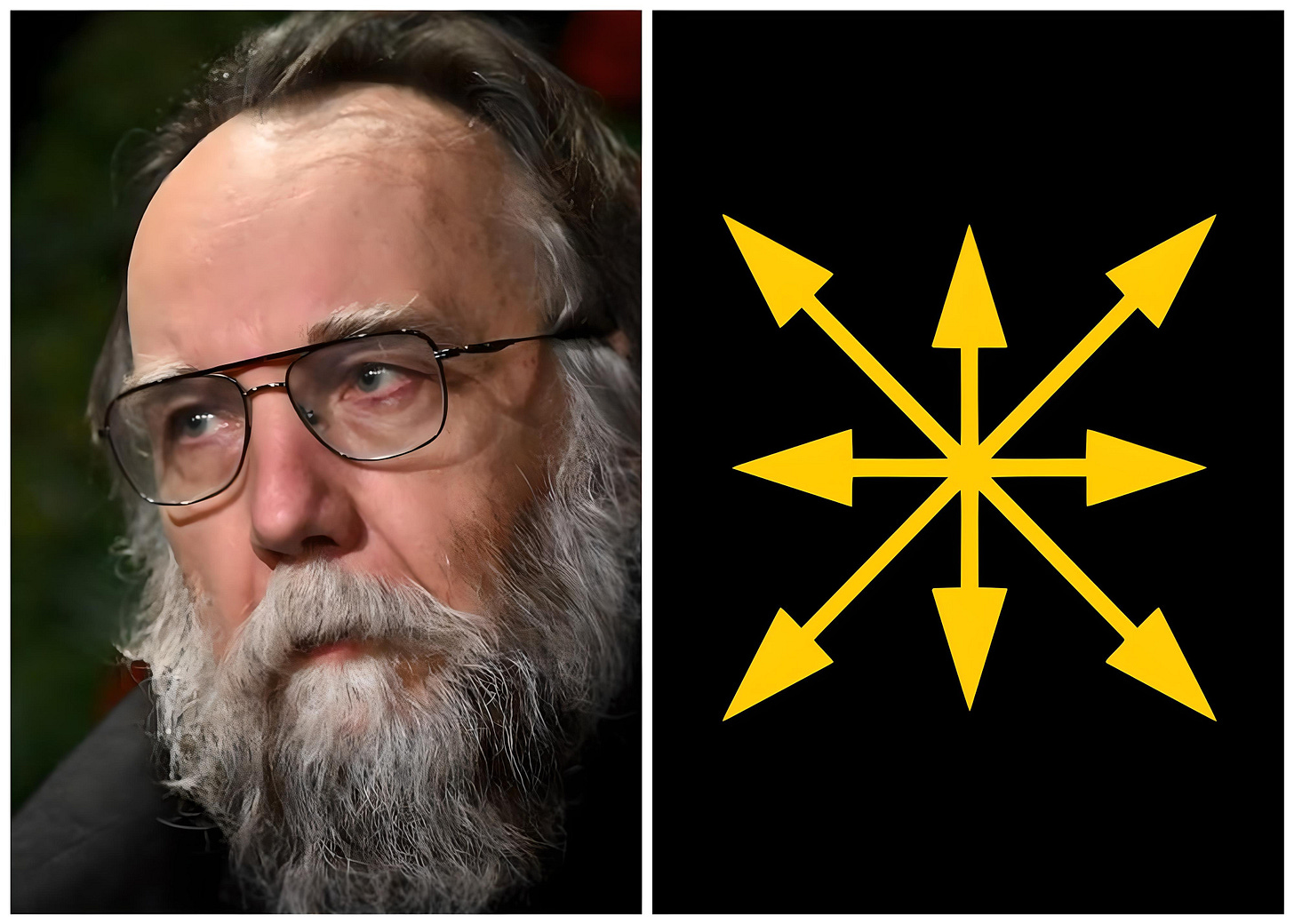

Alexander Dugin’s Eurasianism

The unique and sovereign development paths of ethnicities and cultures

Constantin von Hoffmeister outlines Alexander Dugin’s theories of Eurasianism and multipolarity.

Alexander Dugin pushes for a reconsideration of Eurasian values and identities distinct from those propagated by the West (such as uncontrolled mass immigration, extreme individualism, and bizarre gender politics). His argument is grounded in the belief that the unique historical, cultural, and geographical factors of the Eurasian region should inform its political and social structures, rather than adopting Western models of democracy and capitalism.

Dugin seeks to redefine the global order by forcing the emergence of a multipolar world, where different civilizations can flourish independently of Western hegemony. He draws heavily on the historical context of Eurasianism, which began in the interwar period, evolved through the Soviet era, and culminated in Dugin’s thought, which rejects the universalist claims of Western liberalism and promotes a pluralistic worldview, asserting the unique and sovereign development paths of ethnicities and cultures.

In the crazy era of the 1920s, following the upheavals of the Russian Civil War, the sons of Eurasia, exiled in Europe, pondered upon Russia’s ordained place amidst the world’s arena. This was a time when the guardians of Eurasianism stood defiant against the Western demand to mentally traverse from East to West.

Nikolai Trubetzkoy, Petr Savitsky, Lev Gumilyov, and George Vernadsky were foundational figures in the early Eurasianist movement, each contributing unique intellectual perspectives on Russia’s cultural and geopolitical identity. Trubetzkoy, a linguist and philosopher, posited Russia as a cultural bridge between East and West. For Savitsky, Russia’s “middle ground” forms the core of its historical identity; it is neither an extension of Europe nor a segment of Asia. It stands as an independent world, a unique spiritual and historical geopolitical reality that Savitsky referred to as “Eurasia.” Gumilyov, influential for his theories on ethnogenesis (the process by which a distinct ethnic group forms and develops, often emerging from a complex interplay of social, cultural, and historical factors), infused Eurasianism with a dynamic understanding of cultural vitality. Lastly, historian Vernadsky provided a scholarly perspective on Russia’s historical ties with Asia rather than Western Europe, reinforcing the ideological framework of Eurasianism with a detailed analysis of Russia’s past. Together, these thinkers framed a vision of Russia as a unique Eurasian entity, distinct from Western European influences and integrally connected to its Asian heritage.

Embracing a strong allegiance to a distinctive Russian-Eurasian identity, they saw it not simply as a melding of East Slavic and Finnish heritages but as enriched by the traditions of Mongolian and Turkish cultures.

This band of thinkers, building upon the ideological foundation laid by the Slavophiles of the nineteenth century, who had scorned liberalism and proclaimed a sovereign Russian civilization apart from the West, now rebelled against the Western universalism that sought to encompass all dimensions of life. They challenged the essence of Western dictates, rejecting the notion that every nation must conform to democracy in the Western mold and that all economies should be shackled by the chains of free market capitalism. These mandates were resolutely dismissed by the heralds of Eurasianism.

Central to their doctrine was the concept of passionarity, a term coined by Gumilyov to describe a phenomenon that engenders an active and intense lifestyle among the steppe peoples. This, Gumilyov argued, was not merely a cultural trait but a genetic mutation within the ethnos that spurred the emergence of passionate warriors — individuals driven to shape the destiny of their people. This theory wove a compelling narrative of resistance and identity, firmly rooting Eurasianism in the soils of its diverse and historic lands, functioning as a dam against the sweeping waves of Western influence.

Dugin sees the final step in the development of Eurasianism in the Fourth Political Theory — a new political framework centered around Martin Heidegger’s concept of Dasein, or “being-there,” which Dugin interprets as the people — which aims to transcend modern political ideologies. In this theory, he deconstructs and combines elements from liberalism, Marxism, and Fascism/National Socialism, discarding their problematic aspects and emphasizing their positive traits, such as the freedom of liberalism, the critique of liberalism by Marxism, and the ethnocentrism of Fascism, to form a foundation that every people can use to preserve its identity and establish a political order reflecting its cultural uniqueness.

Dugin’s critique extends to the economic and political frameworks imposed by the West, proposing instead a model where civilizations define their interactions based on their cultural and historical contexts rather than global market forces. He highlights the importance of sovereign states and civilizations over international bodies and agreements, which often reflect Western interests. By emphasizing local economies and cultures, Dugin’s approach opposes the free market and capitalist ideologies that dominate global economics today.

Central to Dugin’s thought is the idea of the “great space,” a geopolitical concept — originally devised by the German political theorist Carl Schmitt in the 1930s — that transcends traditional nation-states to form regional conglomerates based on cultural, historical, and geographic commonalities. These great spaces — essentially empires or “state-civilizations” — are envisioned as self-sufficient entities that resist the cultural and economic pressures of globalization, supporting local governance and autonomy instead of centralized, universal power structures.

Furthermore, Dugin infuses his geopolitical theory with a deep sense of cultural and spiritual revivalism. He favors a reorientation towards traditional values and norms, seeing this as essential for resisting the homogenizing impact of modern Western anti-culture. This revival is not merely nostalgic but serves as a foundational principle for a society that prioritizes community, tradition, and spiritual health over material wealth and individualism.

The philosophical underpinnings of Dugin’s theory are heavily influenced by the Conservative Revolution, an intellectual movement in Weimar Germany that aimed to rejuvenate German culture and society by drawing on conservative and nationalist values, seeking to restore a sense of order and tradition in the wake of perceived societal decay. Schmitt’s distinction between land and sea powers is particularly relevant, framing the conflict between globalist maritime nations (typically Western) and the traditionalist continental powers of Eurasia. Dugin uses this framework to position Eurasia as a natural counterbalance to the maritime dominance of the US and its allies, championing a reassertion of land-based power in global politics.

Dugin’s vision for the future also includes a restructuring of global alliances and economic zones. He proposes the creation of several geo-economic zones that reflect cultural and economic realities rather than existing political boundaries. These zones would foster economic independence and cultural cohesion, reducing reliance on Western economic systems and potentially creating a more balanced global power distribution.

In summary, Dugin’s vision is a radical critique of and alternative to the liberal, Western-centric global order. It champions a return to traditional values, sovereignty, and regional cooperation based on cultural and historical ties. By espousing a multipolar world where all civilizations uphold and celebrate their unique identities, Dugin’s theories challenge the current dominance of Western liberalism and propose a fundamentally different vision for the future of global politics and culture.

Yes to multipolar world definitely. However the illegal immigration and weirdly sick gender politics is due to elite cabal intent to destroy democracy in their effort for world control. Please read Toronto Protocols you can find pdf online for confirmation.